Longing for the return of the New York moment

- Published

Early on, New York City became the epicentre of the US coronavirus epidemic

I write in celebration of the New York moment: those exhilarating and enchanting experiences and encounters that make New York, New York.

Let me give you an example from the blackout that immobilised this city in 2003, a power outage late one lazy August afternoon that many of us feared signalled the start of another terror attack - a second 9/11.

Thankfully, the lights had gone out because of America's decrepit power grid rather than anything more sinister, and relief quickly turned to revelry. Bars spilled out onto the sidewalks. Blocks of Manhattan became the venue for twilight raves - part carnival, part catharsis.

With traffic in Manhattan brought to a standstill, many New Yorkers repurposed themselves as human traffic lights, and for some of the Big Apple's more operatic personalities the clogged avenues became a stage. At the intersection where Sixth Avenue meets Central Park, one man orchestrated the traffic with such exuberance and gusto that he resembled a maestro conducting the symphony at nearby Carnegie Hall.

"You look like you've done this before," I said, approaching him with my cameraman at my back. "Well, I play a cop on TV," he replied, as he hoisted his handkerchief high into the air. And he did: the FBI agent on the hit series, The Sopranos.

New York's subway carriages have become makeshift dormitories for the city's homeless after dark

Another New York moment came a decade ago, when my wife and I were visiting the city with our baby son. Over lunch at a café in the East Village, Billy charmed and flirted with the couple at the table next door. So much so, that at the end of their meal, the man approached us holding out his business card. He was a photographer who specialised in taking portraits of infants on their first birthdays, and given that Billy was approaching that age, he offered to take his picture free of charge.

It was a generous offer, but not one that we gave that much thought to. Until, that is, I pulled his business card from my pocket in the taxi afterwards and saw on it the name "Mapplethorpe". That seemed to be more than just a coincidence; more than some cosmic fluke. And sure enough, it turned out he was the brother of one of New York's most celebrated photographers, Robert Mapplethorpe.

Edward had built his own reputation by taking portraits of one-year-olds that in New York elite society were viewed as works of high art. So quickly we arranged to meet him at his studio, where Billy sat for the most beautiful photo that has ever been taken of him, and we were given snapshots into the world of Robert Mapplethorpe, the gay Manhattan subculture of the Seventies and Eighties, the community devastated by the last pandemic to rip through this city.

I could tell you about the a capella singing group that rehearses in the stairwell of my apartment building: world-class musicians whom I have never cast my eyes on but whose close harmonies drift to the upper floors, transforming this most soulless of concrete settings into an acoustic cathedral.

I could relive the time I spent with Donald Trump in Trump Tower talking about the demise of his old casino empire in Atlantic City, a financial calamity which, needless to say, had nothing to do with him. And back then, in 2014 when we met, that really did feel like a New York moment, because he did not strike me as a figure of wider consequence. After we shook hands and parted, I walked out of the golden doors of his fiefdom on Fifth Avenue not expecting to report on him again.

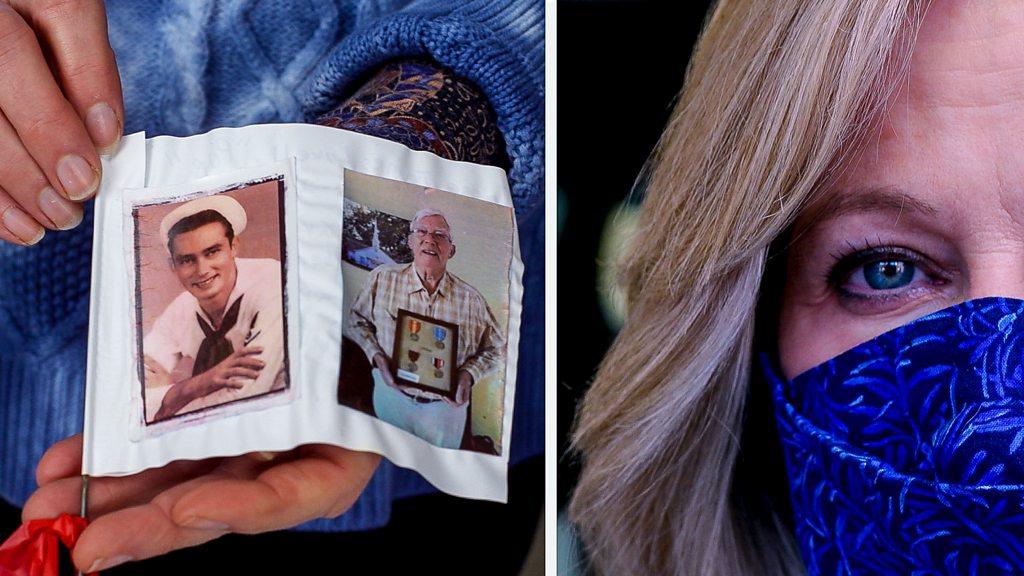

An estimated 3 million New Yorkers have fled the city since the pandemic began

But the New York moment that recently has been looping in my mind reaches back to the months after September 11th, that period in the life of this city when its residents became unusually kind and sensitive towards each other; when voices were softened; when a ceasefire was observed bring to a temporary halt many of the daily skirmishes of urban life.

It was the rush-hour, a trumpeter was blasting out the most discordant of tunes, and I watched unblinkingly as a middle-aged woman wearing a smart trench-coat clearly felt she could no longer abide by the terms of New York's behavioural armistice. She walked right up to the trumpeter, so that she was standing right in his face - a customary New York stance - and then let rip.

"Shut the [expletive] up!" she yelled. "Just shut the [expletive] up." I remember watching with a sense of profound relief. After suffering the most harrowing day in its history, New York was returning to normal. The question on so many mask-covered lips right now is not just when will New York return to normal, but can New York return to normal?

As I write, more than a year after the Coronavirus first struck, the city continues to appear before us in a phantom-like form, a ghostly Gotham. It's thought that a third of the city's small businesses closed down in 2020 - dive bars, diners, kosher-delis, family dry cleaners, barber shops, nail salons, and the bodega convenience stores that have always prided themselves on being open all hours.

Six months of struggle: How one New York bar tried to survive

It's also been estimated that more than three million people have fled, an exodus of rich New Yorkers seeking refuge in second homes; an evacuation of struggling students returning to live with their parents; an exit stage right of actors and actresses lured here by the bright lights of Broadway who have nowhere to perform now that the Great White Way is dark.

We have seen an influx of new arrivals, but the city has been shrinking before our eyes.

And what of those people who've recently made New York their home? It's hard to imagine they've been drawn here with the same sense of optimism and ambition; that magnetic belief in the inevitability of their upward mobility; the romance of being penniless in a city where so many have made their fortunes. How can they possibly be carrying that passport of possibility traditionally brandished by the new New Yorker?

That, in turn, raises one of the nagging intangibles of the Covid crisis. What will be the long-term impact on the spirit of New York? What will be the viral impact on the psyche of this city? State and civic leaders have rightly applauded the resilience and instinct for survival. "New York Strong" has been the hashtag. But this is a city built not just on doggedness and defiance, but a congregation of dreams.

Read more from Nick

The Big Apple has bounced back before. From the fiscal crisis of the Seventies, the crime wave of the Eighties, a commercial property slump in the Nineties, the destruction of the Twin Towers, the collapse of Lehman Brothers investment bank, which precipitated the Great Recession.

But this convulsion is of a different magnitude altogether. 9/11 traumatised the entire city, but the economic disruption was fairly localised to Lower Manhattan and the area around Ground Zero. Even as the towers were aflame, most of New York continued to function. Likewise with the financial meltdown, the city was never halted in its tracks. And the very things that had always made it prosper - the alchemy that comes from having so many driven people living cheek by jowl - provided the means of recovery.

The ecosystem of this city relies on skyscrapers full of office workers and streets thronged with tourists. But neither of those things exist right now, and won't for some time to come. And the simple fact that New York was the epicentre of the American outbreak means it will suffer more serious long haul effects. The unemployment rate here was twice the national average. Economists fear an elongated recovery, two years longer than other parts of the country. For a full revival, the time frame I commonly hear is a decade.

In the meantime, we are daily confronted with the dispiriting New York moments of coronavirus life. The sight of 24-hour food banks serving the needy round-the-clock. The subway carriages that serve as dormitories for the homeless after dark. The family businesses that have shut their doors forever. The outstretched hands of beggars at the foot of so many skyscrapers.

Eventually, this city will rally. I promise you this is not a requiem for New York, an elegy that has been performed way too many times before. This is a place not just of personal reinvention but recurring civic renaissance. But if that discordant busker is still blowing his trumpet, then play for us again. We need your tuneless fanfare more than ever.

- Published22 February 2021

- Published20 February 2021

- Published22 February 2021