The mystery American woman wanted in the UK

- Published

Anne Sacoolas, a US citizen, has been charged with causing death by dangerous driving in the UK, but returned home under the protection of diplomatic immunity. That doesn't mean she's escaped accountability.

In August 2019, Anne Sacoolas collided with motorcyclist Harry Dunn while driving on the wrong side of the road in the UK.

The 19-year-old was taken to hospital and later died. Sacoolas returned to the US, claiming diplomatic immunity, and an extradition request was blocked.

But a US judge, TS Ellis, has said she must face the music, at least in civil court.

He ruled last month that a lawsuit filed in the US state of Virginia by Dunn's family could go forward. They are claiming wrongful death.

On Wednesday, Judge Ellis said the family could also pursue a damage claim against Sacoolas' husband. She was driving his SUV when the collision occurred.

Judge Ellis chastised Sacoolas in a court teleconference last month: "Accepting full responsibility doesn't mean you run away."

Ellis is a conservative judge, known for rulings that protect the government, especially the intelligence agencies. So his criticism of Sacoolas, and his decision to allow the civil claim to proceed, were surprising.

Sacoolas was charged in the UK with "causing death by dangerous driving", but has remained on US soil.

Harry Dunn died in hospital after his motorbike was involved in a crash outside RAF Croughton

The case has created tension between the two countries, with UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson saying this month his government would do "whatever we can to get justice" for Dunn.

And the decision to allow her to escape justice in the UK has infuriated the Dunn family and their supporters, who have made direct appeals to the US government to have her sent her back to Britain.

State department officials say she has diplomatic immunity, a rule that dates back to the 1961 Vienna Convention protecting diplomats while they are working abroad. It was a privilege she was granted as the wife of a US intelligence officer, working in Britain for the US embassy.

Sacoolas' lawyer said she has taken responsibility for the collision, which occurred near RAF Croughton, the air force base in central England where her husband worked.

Floral tributes mark on the roadside near the collision

In a statement released through her lawyer, she said she very briefly was instinctively driving on the wrong side of the road when the crash occurred, and did everything she could to help Dunn.

The Dunn family wants her to face trial in the UK. So does British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, who said letting her stay in the US, instead of returning to Britain for trial, was a "denial of justice".

She has not, however, escaped justice entirely.

National security lawyer Mark Zaid says the federal court in Virginia's Eastern district, where Judge Ellis presides, is the worst possible venue for those who are fighting the intelligence agencies: Ellis is "incredibly pro-CIA".

For that reason, the judge's criticism of Sacoolas, and of the government, was unusual, says Zaid: "Folks should really pay attention."

Sacoolas, 43, grew up in Aiken, South Carolina, and graduated from University of South Carolina. By 2003, she was living in Virginia, according to a wedding announcement in her hometown newspaper.

She studied psychology and was "worldly, sophisticated", says an old friend, Aaron Howard, who met her while he was tending bar: she drank negronis, a gin cocktail.

'It's just another hurdle' Harry Dunn's parents say

Her house in Virginia was set back from the street, filled with sturdy, childproof furniture, exercise machines and books about espionage: a copy of Peter Maas's Killer Spy, a book about a CIA mole, Aldrich Ames, sat on a shelf.

But Sacoolas' occupation has been a bit mysterious.

Her lawyer, John McGavin, said during a hearing last month that she worked for a US "intelligence agency", and that this had been "a factor" in her decision to leave the UK after the collision.

Then, a moment later, he corrected himself, saying she worked for the US State Department.

When the judge asked whether her job at the State Department was cover for her intelligence work, her lawyer said he did not have that information.

Sacoolas, her husband and their three children live in northern Virginia, a place with ornamental shrubbery, wide streets and American flags.

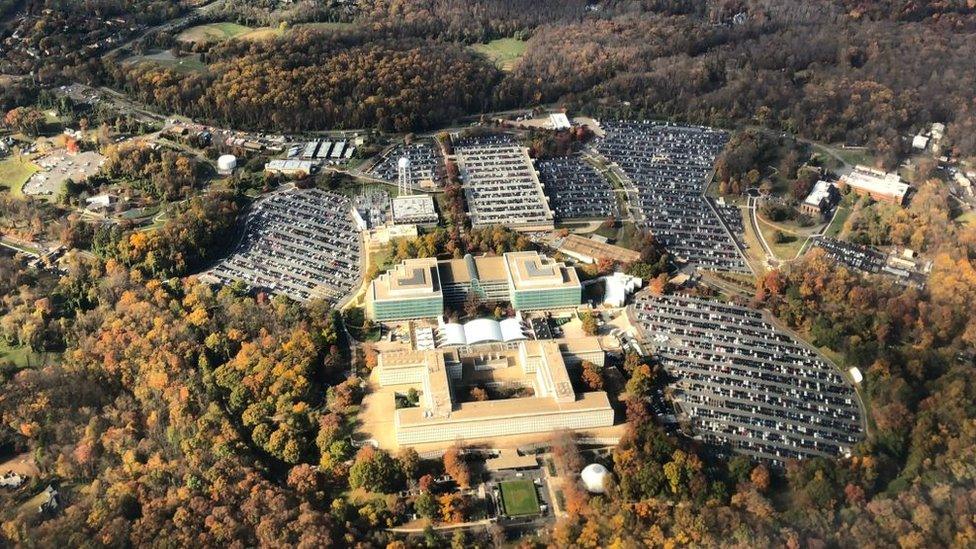

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters are located here, and many of Sacoolas' friends and neighbours have jobs that are similar to the ones the couple hold - they work for the government, and for the intelligence services.

Sacoolas' diplomatic immunity has set off a debate in the US, and within the intelligence services, about the sweeping powers of intelligence officials and their families.

The immunity is meant to protect officials from false charges by a hostile government. The UK is an ally, though, and many were surprised when she left and avoided trial.

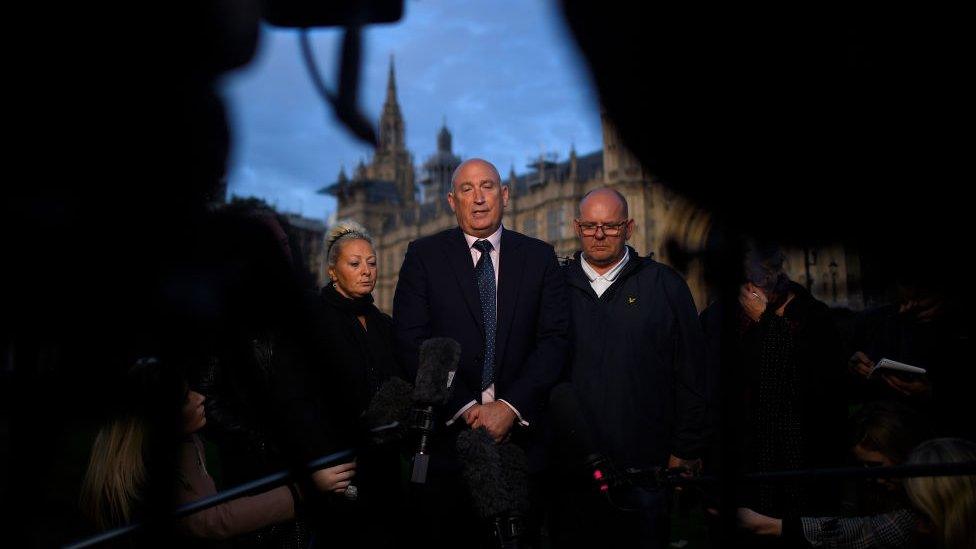

Family spokesman Radd Seiger, flanked by Harry Dunn's parents, Charlotte Charles and Tim Dunn

Under former president Donald Trump, federal officials defended her in a forceful manner.

A spokesman for Dunn's family, Radd Seiger, recalls the family's visit to the White House in 2019. They were asked to meet with Sacoolas, who was waiting nearby. They refused.

Before they left the West Wing, Seiger says then National Security Adviser Robert O'Brien told them: "She's never going back".

Seiger and others thought the situation might change with the new president, Joe Biden. So far, it has not.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki tells me that she has been following the Sacoolas story on the BBC, but deferred questions about the case to the State Department. State Department spokesman Ned Price says their position is clear: Sacoolas has diplomatic immunity, and their decision is "final".

Diplomatic immunity 'sacrosanct'

The US defence of Sacoolas has come under increasing scrutiny.

Lawyer Zaid says: "We [the US] obviously have full faith in the British legal system, so it's somewhat shocking that we up and ran."

"Diplomatic immunity is not meant to shield our people from criminal or negligent activity. It is supposed to protect our diplomats from a hostile foreign government."

A former acting general counsel for the CIA, Robert Eatinger, says he understands why the officials have held the line.

If they made an exception for Sacoolas, he says, it would set a precedent.

Diplomatic immunity is "one of the things that the US considers sacrosanct," he says, adding: "Once you've waived it for Mr So-and-So, it opens up other issues."

The CIA headquarters is located in Langley, Virginia

The officials may have good reasons for their decision. One possible concern is that the US wanted to protect operations - a trial could expose details of intelligence work.

Yet the waiver can still seem wrong to people.

"There's an understanding at one level," says Eatinger, formerly of the CIA. "But at the other level, the human level, this just seems unfair."

A former CIA officer, Ilana Sara Greenstein, says the decision to grant diplomatic immunity reflects a certain mindset within the industry.

"There's a little bit of the God complex," she explains, describing the culture of the agency. "People walked around thinking: 'We can do what we want.'"

In her view, diplomatic immunity for Sacoolas reinforces this belief.

'She has to accept responsibility'

Today, Sacoolas's Virginian home is rented out, and she is living elsewhere while the civil case makes its way through the court.

One breezy afternoon last week, Jerry Haskins, 70, was next door to her old house. The road smelled like pine, and whitetail deer roamed through back lots. He looked down a long driveway, pointing to a spot where he first met her.

"She was friendly enough," he says. "She walked up and introduced herself. I told her: 'Nice to meet you.'"

Today, he shakes his head.

"She has to accept responsibility," he says. "Why didn't she stand trial?"

Another neighbour, an IT expert who was striding past her house during his regular, mile-and-a-half walk, says she should have faced the consequences, rather than head home. "You own it up," he says, then continued on his way.

Related topics

- Published4 March 2021

- Published3 March 2021

- Published17 February 2021

- Published20 December 2020

- Published18 February 2021