What is a hate crime in the US?

- Published

A 21-year-old white man, Robert Aaron Long, has been charged with eight counts of murder in connection with attacks on Atlanta-area spas, killing eight people, six women of Asian descent.

After he was arrested, police said he admitted to the shooting spree and they said he denied the shooting was racially motivated. The suspect spoke instead of "sexual addiction", telling police he had carried out the assaults in order to get rid of "temptation".

Though officials have not named a motive, the shooting has highlighted the issue of hate crime - a growing scourge in the US. The definition of hate crime is a legal matter, but it encompasses political and cultural issues, and is, for many, personal.

Here is a look at some of the key aspects of the issue.

What constitutes a hate crime in the US?

A hate crime is a criminal offence, one motivated by bias toward gender identity, ethnic background or race: the perpetrator selects their victim because of who they are, or who they are perceived to be.

In some cases, prosecutors will use federal law to charge an individual with hate crime.

The first federal hate crimes statute was signed into law in 1968, external, and it has been expanded several times since, such as including protections on the basis of disability.

In 2009, Congress passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expanded the federal definition of hate crimes.

More often, prosecutors rely on state statutes. The laws, and punishment for the offence, vary from state to state. Overall, the designation of hate crime means the perpetrator will receive a harsher sentence, or additional time behind bars.

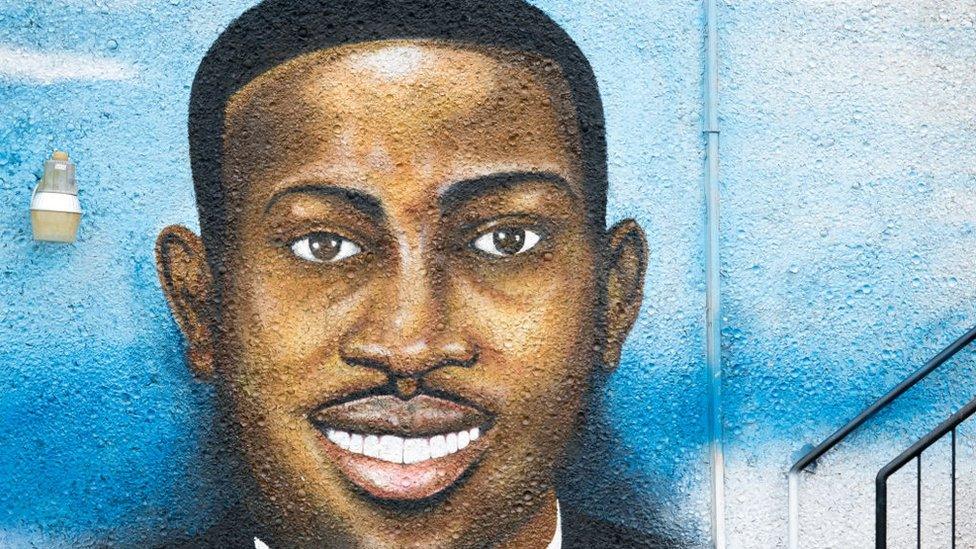

Georgia brought in a new hate crime law after the death of Ahmaud Arbery

In June, Georgia, where the shootings occurred, passed a new hate crime bill. It imposes harsher penalties for offences motivated by a victim's actual or perceived race, colour, religion, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender or disability.

But Atlanta police have said it was unclear whether the Atlanta shooting might constitute hate crime, as legally defined.

Many Asian-Americans and others view his actions as racially motivated, however, and believe he should be charged with hate crime.

When has the hate crime designation been used?

In some cases, the designation of hate crime is straightforward: Dylann Roof described himself as a white supremacist, and was charged with hate crimes involving the shooting of black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. He was sentenced to death.

Robert Bowers killed 11 people in his assault on a Pittsburgh synagogue in 2018. Prosecutors said he had posted disparaging messages on social media about a Jewish charity group and about refugee aid. He was charged with hate crime violations. His case has been delayed because of his efforts to get some of the charges dropped, and due to the pandemic.

In other cases that appear to be racially motivated, hate crime charges have not been filed.

In 2015, Craig Hicks shot and killed three people who lived near him, all of them students of Middle Eastern descent, in a condominium complex in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Some neighbours said they had heard him use racial slurs before the shootings, but others said they saw no signs of racial bias.

However, in North Carolina, hate-crime law does not apply to first-degree murder. The case was not prosecuted as a hate crime, and he was sentenced to life without parole.

How does the designation of hate crime in the US compare to laws in other countries?

The legal understanding of hate crime is different in the US than in other countries because of the US Constitution and the legal interpretation of the document.

The US Supreme Court has heard numerous hate speech cases

The first amendment of the Constitution protects free speech, even hateful or biased language. There are limits: a person cannot, for example, shout "fire!" in a crowded movie house when there is no danger.

According to the American Bar Association, "hateful speech that threatens or incites lawlessness or that contributes to motive for a criminal act may, in some instances, be punished as part of a hate crime, but not simply as offensive speech".

Yet hateful language is protected in the US, in a way that is not allowed in other countries: hate speech is classified as a crime in the UK, Canada, and the European Union.

Why is the classification of hate crime important?

When hate crimes occur, an entire community can feel threatened.

Defining an act as a hate crime can reassure those within a community that they are protected, says Janice Iwama, of American University in Washington.

If hate crimes are not recognised, she says, people may feel as though the law does not extend to them, or not in the same way: "They can be attacked, and nobody's going to anything about it."

Other legal experts agree that the designation of hate crime is important for social and cultural reasons, too.

Jordan Blair Woods, a professor at University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, says that calling an offense as a hate crime, in the legal sense, goes beyond the question of sentencing: "It's not just: does a person get more or less years behind bars?'.

"The effects of this type of violence bleeds out, into an entire community. To have this type of violence recognised is part of being included. It shows that a group is recognised, not only by the government, but also by the general community."

Related topics

- Published22 November 2021

- Published22 March 2021

- Published18 March 2021

- Published18 March 2021

- Published18 March 2021