Chauvin trial: Who are the jurors who will decide the former police officer's fate?

- Published

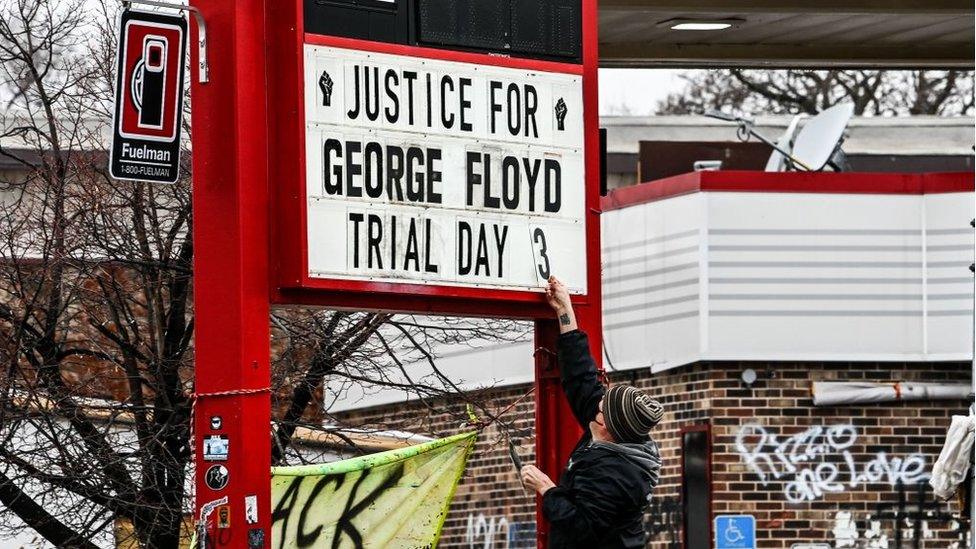

A protest in Minneapolis ahead of the trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin

Two legal teams fought tooth and nail over three gruelling weeks. This week, they rounded out the jury panel for arguably the highest profile murder trial in Minnesota history.

Former police officer Derek Chauvin goes on trial next Monday on two counts of murder and one count of manslaughter over the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man, last May in the city of Minneapolis.

Fourteen jurors, who will remain anonymous and unseen throughout the televised trial, will decide whether Mr Chauvin should serve time in prison or be acquitted.

Whatever the final verdict in this highly publicised case, it will likely have implications for the Black Lives Matter movement and the future of policing in the US.

Who are the jurors in the Chauvin trial?

Selecting jurors in an emotionally charged case over a black man's death at the hands of a white police officer was no easy feat, but it was made even more complicated in the George Floyd case because of how well known his death was.

After 11 days worth of summons, the two opposing legal teams settled on 15 Minnesota residents out of a jury pool of over 130 people.

Among that group, 14 - including two alternates - will be sworn in next Monday, while the 15th juror is a backup option, in case a juror drops out before the trial begins.

The jury panel skews younger, more white and more female.

It includes a black grandmother in her 60s, the oldest member of the jury, who said she stopped watching the infamous video of Mr Floyd's death because "it just wasn't something I needed to see". She also claimed she used to live 10 blocks from where he had died.

Others too admitted that they found the video difficult to watch, with one newly-wed white woman, a social worker in her 20s, saying "I had every emotion".

The Floyd video may become the centrepiece of this trial, but prospective jurors were also questioned about their opinions on the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, the opposing Blue Lives Matter movement (which advocates for police officers), the push among activists to "defund the police" and the violence associated with some BLM protests.

A white woman in her 50s claimed she used to work at a suburban business damaged last summer after Mr Floyd's death. She had seen the video, but said she generally trusted the police and felt that those who followed instructions had nothing to fear.

A black man in his 40s said that, while he believed minorities are mistreated regularly by the police, he strongly disagreed with defunding - or redirecting funds away from - police departments.

How will the makeup of the jury affect the Chauvin trial?

In Hennepin County, where the trial is being held, white people make up nearly three-quarters of the population, according to US census data.

It is also home to a large immigrant population, slightly higher than the national average.

So the makeup of the jury is "a mixed bag", argues Jason Nichols, a progressive political and social analyst who teaches African American Studies at the University of Maryland.

He says jurors will find the visuals of Mr Floyd's death deeply affecting: "Once you turn that video on, it's hard to watch. We saw, in its aftermath, that was the highest Black Lives Matter had ever polled."

"But imagine you're somebody who looks at that situation and thinks 'that could be me,'" he added, in a nod to the six people of colour on the jury.

Mr Nichols cautions, however, that we cannot pre-judge how a juror will operate.

Some of the white jurors may be progressives who view the Floyd video as "an egregious case of racism", he said, whereas the other ones may not "see their husbands or fathers" in Mr Floyd if the defence portrays him as a 6-foot-4 black man under the influence of drugs and behaving erratically.

At least one black juror is an immigrant, not an African American, and Mr Nichols says "they may not see themselves in George Floyd because their connection to police brutality is different".

Regardless of background, he said: "It's going to be really interesting to see where the American people are, how unified we are and how willing to accept evidence, whether it's positive or negative."

How were jurors selected?

All potential jurors completed a 16-page questionnaire before arriving in the courtroom. Questions asked them to weigh in on policing in the US, racial discrimination, Black Lives Matter, Blue Lives Matter, their own interactions with police and their level of familiarity with the Floyd case.

Inside the heavily-guarded courtroom, Judge Peter Cahill swore in each person before they were questioned one-by-one, a process known as voir dire.

Mr Chauvin's lead attorney, Eric Nelson, posed questions on behalf of the defence, while Steve Schleicher questioned members of the jury pool for the prosecution.

Each juror was only identified by a number. No names, addresses or other identifying details will be revealed at any time and they will not be shown on screen.

A sensitive process was made even more complicated last week, when the city of Minneapolis settled a wrongful death civil suit with the family of Mr Floyd for a record $27m (£19.7m), the largest in the state's history.

It forced Judge Cahill to dismiss two jurors who had been previously selected, as well as excuse at least three prospects, after they admitted the payout had influenced their opinions on the case.

FACT BOX: Excusing potential jurors

Judge Cahill and the two legal teams could dismiss members of the jury pool for cause, if they felt the person could not be fair and impartial.

Both legal teams could also strike jurors without cause, typically because of concerns about views they have expressed in the questionnaire or voir dire.

The Chauvin defence team was allowed 18 challenges and used 14.

The state of Minnesota's prosecution team used eight of its 10 allocated challenges.

Either team could also challenge the other's challenges if they believe it to be on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity or religion.

Members of the jury pool who were excused often expressed strongly negative views on Mr Floyd, Mr Chauvin or other related topics.

One woman, a nursing assistant, told the court she joined a protest after Mr Floyd's death because she believed: "It was not his time to die, and the incident should not have gone as far as it did."

Another woman, a mother of five, denounced the violence in the wake of Mr Floyd's killing, saying: "There is more crime than there was before. The reputation of the city seems to have taken a hit."

It is all a sign of just how high the stakes in this trial are.

What might be the impact of this trial?

Mary Frances Berry, a former chairwoman of the US Commission on Civil Rights, says the trial will be "a test of whether the Black Lives Matter protests still have potency".

Ms Berry says "even under the best circumstances, police officers are not convicted of murder and can argue that what they did was reasonable".

"We're at a moment when whether or not we are going to do something about reforming police is very much contested," says Ms Berry, who noted the jury's verdict must be unanimous.

If Mr Chauvin is convicted, she says it will be "a departure" from past practice and will "send a signal to police that these kind of behaviours are not valid".

But if he is not, "it signals that, no matter how bad the behaviour and no matter what you see with your own eyes, police are so supported and they can get away with killing unarmed people under these circumstances", she said.

Mr Nichols agrees, calling it "a pivotal moment in our culture". He says African Americans have seen several miscarriages of justice, especially in recent years, and does not view the justice system as valuing their lives.

A conviction for Mr Chauvin will bring only "a brief sigh of relief", he believes, "because we're only waiting unfortunately - until we have real systemic change - for the next George Floyd situation".

"Justice looks at the facts and justice makes a fair determination. And, thus far, we have not seen that," he said.

"People are going to pay attention to this trial."

- Published24 May 2021

- Published16 July 2020

- Published10 March 2021

- Published21 April 2021

- Published9 March 2021

- Published23 March 2021