Alaska's first CSI takes on blood and burglaries in sub-zero weather

- Published

Alaska, the Last Frontier state, now has its first and only crime scene investigator. What drew the native Alaskan to the forensic sciences?

Two years into her justice degree at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Shasta Pomeroy went on a ride-along with the local police and was allowed to observe an outdoor crime scene.

At the time, she was unsure of her future. She was taking law classes, but knew she didn't want a career as an attorney.

That night changed everything for her.

"I knew that I wanted to be on scene. I was never more sure of anything in my life. My family were surprised, but they were super supportive," she says.

Pomeroy completed the law classes, but it was a five-week study trip one summer to University of California Riverside, some 55 miles (88km) east of downtown Los Angeles, that was her leap of faith.

"The crime scene investigation certification was expensive, and it meant travelling into the Lower 48," she says. "I was really seeing if this was what I wanted."

She learned about crime scene photography, bloodstain pattern recognition, collecting DNA, entomology (insect) samples and more, and it quickly confirmed she had made the right choice.

"I'm not emotion-driven, and I can't explain it, but I just knew."

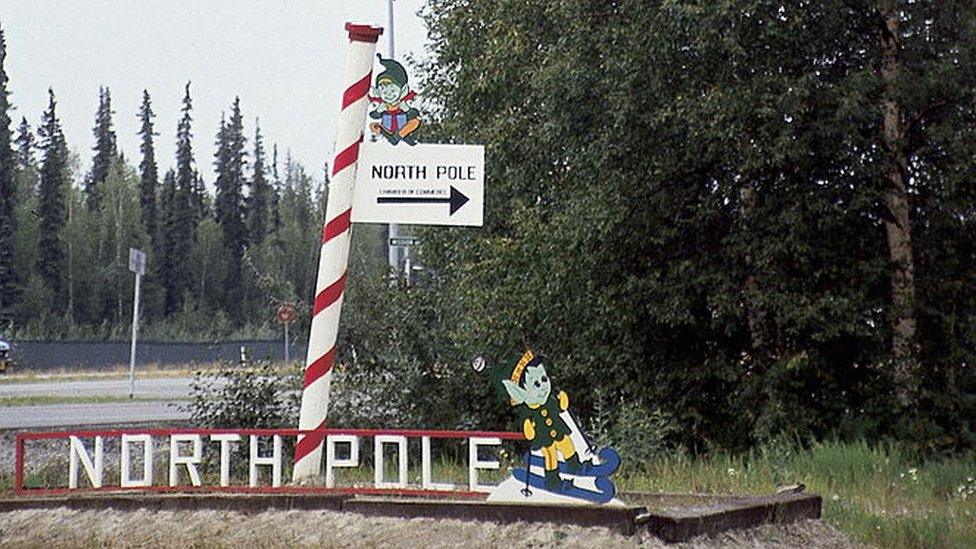

She was born in Oregon but raised from infancy in North Pole, a small Alaska town about 15 miles south of Fairbanks, where it always feels like Christmas, with year-round decorations and a Santa Claus House.

In 2016, Pomeroy joined the Fairbanks Police Department [FPD] as a data clerk but would study in her down time and read forensic science books "for fun".

She then became an evidence technician, preserving and packaging evidence for later analysis by scientific investigators, and while she worked "tagging and bagging", she completed her Masters in Administration of Justice. Her final project reviewed the use of forensic science in law enforcement, and how it could apply within Alaska.

She had one goal in mind.

Over the next few years, she undertook further forensic science training through the state's medical examiner's office, the state crime lab, in Las Vegas, and online, and finally this March she was named as the first ever CSI (crime scene investigator) at the FPD.

"I respect and care about the people here, and I wanted to go where I was needed," she says.

Her accomplishment wasn't just limited to the "Golden Heart" city - population 31,500 - as her appointment also meant she was the first ever CSI in the entire state of Alaska.

Just back from a "fantastic" week's training at the Death Investigation Academy in Missouri, Pomeroy, 30, spoke enthusiastically about her journey.

"Prior to me, detectives and others would get specialised training, and the State Troopers had a technician who would attend scenes."

She frequently mentions the encouragement she has received.

"This position literally didn't exist. [FPD] Chief Ron Dupee and Deputy Chief Rick Sweet created it for me," she says.

Writing reports is a constant in her duties, though on any random day she could be in the department dusting for fingerprints, processing footwear impressions, collecting DNA samples, or being called out to multiple crime scenes.

"Homicides, suspicious deaths, burglaries - we have lots of burglaries - sexual assaults, aggravated assaults. We deal with everything."

Working in Alaska has some extra challenges.

Heightened privacy laws mean a greater need for search warrants for example - and then there's the famous frigid weather.

"The coldest scene I have worked was -33 degrees, outdoors," Pomeroy says.

"You have to warm up your camera, your batteries, and then your hands, before you can work. If there's a drive-by shooting, the bullet casings will be hot when ejected from the weapon, and then freeze into the snow. You can't get them out wearing thick gloves."

'Sherlockian Principles of close observation'

The "CSI Effect", a television-inspired assumption among the public that crimes can be quickly solved using modern technology, does have some basis in truth, admits Pomeroy.

"We have a 3D, 360-degree imaging technology called Faro, which I'm waiting to be trained on, and handheld alternative light source (ALS), which I use to look for biological samples like body fluids such as semen and saliva at a sexual assault scene."

Like all technology, Faro has some limitations, including the fact it cannot pick up "fungible" evidence like smoke, perfume or flashes of light.

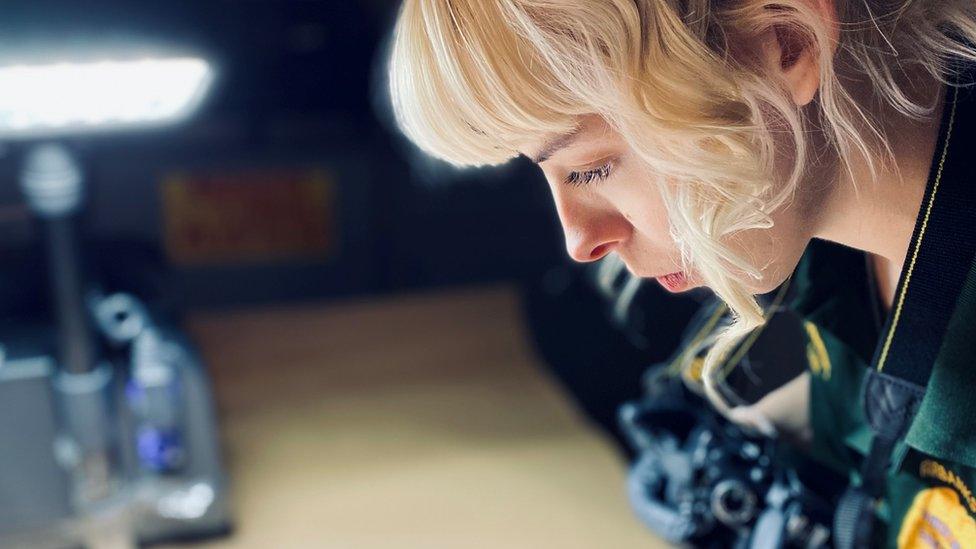

"A lot of my work is on my hands and knees, using the Sherlockian Principles of close observation," says Pomeroy, who carries a Nikon camera and a pocket magnifying glass with LED and UV features with her on every call.

She has found herself on rooftops, or alone in remote, forested areas, of which Fairbanks has many. None of this dulls her passion, though she does admit to relying on coffee, often iced coffee, despite the weather.

'Human nature wants answers'

"I can go a call-out with just an hour of sleep, and no coffee, but it doesn't matter. I'm just excited to get to work. This really is my calling."

Like many other people working in law enforcement, Pomeroy is very physically active when she's off-duty. She says it's "a physical and artistic way of decompressing and expressing myself".

"I've been a ballerina and dancer for years, and I'm an aerialist on the silks and trapeze. I also enjoy singing, and I'm trying to pick up the piano."

Pomeroy admits that she does feel pressure as the first CSI - though not as the first female CSI.

Law enforcement is a notably male-dominated profession, but she's found nothing but support, and she says everyone understands how useful her work can be.

CSIs are usually expected to specialise, and now she's in the field, Pomeroy is looking to obtain certifications in areas such as death investigations and bloodstain pattern recognition and analysis.

She also assists the state medical examiner's office in Anchorage with post-mortem biological sample collection, something that allows the bodies of victims to be released to the family in timely manner.

"Human nature wants answers," she says.

"As one piece of the crime-solving puzzle, I can help give answers to victims, and to the community."