How George Floyd's death changed a small Iowa town

- Published

Maren Beard, shown with Noche, says local farmers sent food to the protestors in Minneapolis

George Floyd's death, and the trial of Derek Chauvin, have shone a light on racial issues in small towns. Yet coming to terms with racism is tough, even for the well-meaning.

Guy Nave, an academic with a Yale PhD, moved to Decorah nearly two decades ago.

The Iowa town seemed idyllic. It had stone buildings, a train depot and Victorian homes that looked like gingerbread houses. Then, shortly after starting his job at a local college, he locked himself out of his house.

He was rattling a patio door when police showed up.

The officer had received a call, and was told "someone who didn't look like they belonged in the neighbourhood was walking around the house", Nave recalls.

That person was a black man - that person was Nave.

There were other incidents. He was pulled over a dozen times for minor violations during his first year living in the town. He focused on work and tried to ignore those incidents.

Guy Nave says many townspeople have embraced the Black Lives Matter movement

Then, in May 2020, George Floyd died while in police custody and townspeople organised a Black Lives Matter march, the first of its kind. The town was waking up.

'We cannot close off from what's happening'

Small towns are slow to change. A point of pride here is that glaciers missed Decorah, located in north-eastern Iowa, some 12,000 years ago, leaving it with rolling hills - a topography that dates back eons.

It had been stuck in time culturally, too. Until recently, racism was rarely discussed.

Floyd's death affected people here deeply, however, and sparked a movement.

"It changed Decorah, in a way where they cannot close off from what is happening all around," says Maria Leitz, an educator.

But not everyone reacted in the same way.

"People were really sad about it," says Leitz. "But I was really mad about it."

Maria Leitz, right, and Nikki Battle are fighting for racial justice in the town

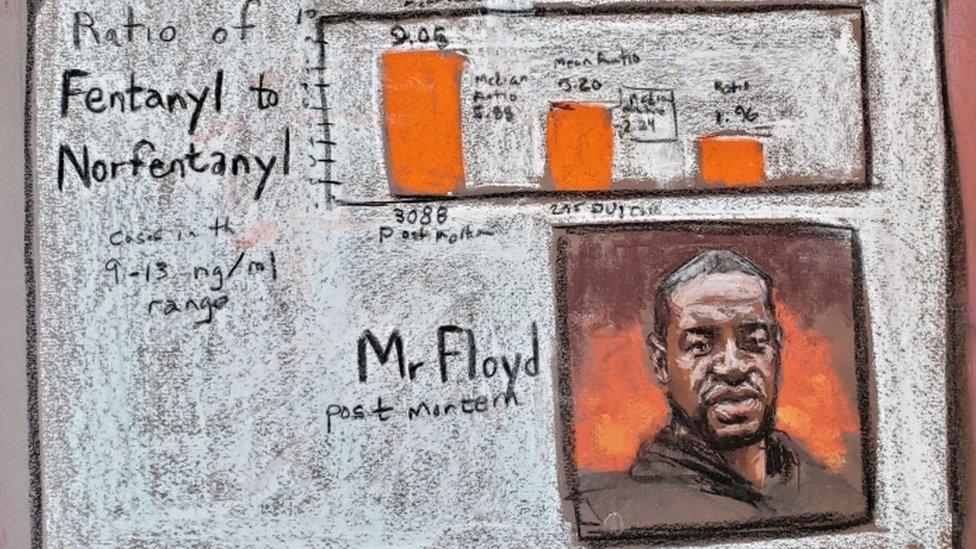

As the trial of Derek Chauvin - the former police officer accused in Floyd's death - unfolds, she pays attention, and watches some of the testimony.

"I do hear snippets," she says. But she has tried to limit how much she sees: "It's just so emotional."

With the trial underway, and as more protests take place in Minneapolis, people here are fighting racism with new energy.

Leitz is now part of a committee - Decorah Human Rights Commission - a group that was established in 2006 to investigate housing and other complaints, but which had languished.

"We're sorting out what Decorah can do," she says. She and other members of the commission have encouraged business owners to put specially designed, black-and-white "All Are Welcome" stickers on windows, promoting an accepting environment.

In addition, Leitz helped to organise the town's Black Lives Matter march, and made posters: "My sign said: 'Change.'"

Not everybody marched but most supported the idea, reflecting a trend of open-mindedness.

More than half of the people who live in rural areas said they sympathised with those who protested in the wake of Floyd's death, external, according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll.

While I was driving through Iowa, the country song, Undivided, played, often: "Why's it got to be all white or all black?"

Leitz was born in El Salvador, and grew up in a town near Decorah.

When she was a child, she says, people called her racial slurs. She left town, lived abroad. One recent afternoon she stood in a field with a friend, also an activist, and looked at the green hills - the landscape that brought her back.

One benefit of her activism has been her new friend, Nikki Battle, who works for an insurance adjuster, and has biracial children. Battle nods, saying: "We fell into a really beautiful friendship."

'These issues can't be on the backburner'

People here say that their town embodies decency, a place where someone will dig your car out of a ditch if you slide off the road.

Here in Decorah, a town founded in the 1800s, locals are trying to promote diversity

Marnie Carlson, a school counsellor, describes it as "a really safe little community". On a recent morning, she chased her daughters, Marit, four, and Daphne, two-and-a-half, and their Old English sheepdog, Rosie, in a park.

Still, she says, small towns can be "pretty insular", and the protest march was a milestone.

"We need to say: 'Hey, even though we're largely white, that's why we need to care about this movement,'" she says. "Just because don't have a lot of racial diversity, doesn't mean we're going to isolate ourselves from what's going on around us."

In a town that is 93% white, filled with people of Norwegian heritage, racial injustice has, until now, not been an issue for the majority.

School counsellor Marnie Carlson teaches children about racial equity: “It’s about respect”

"Most people haven't really met a person of colour," says Jeremy Meyer, who handles billing for a logistics monitoring company. "I think it's something that you just don't think about."

Then George Floyd was killed, and people watched as he took his last breath.

Maren Beard and her husband, Tom, were having coffee in their farmhouse, when she clicked on the video: "Yeah, I mean, I immediately kind of went into a pretty intense, a very physical response. I started sobbing."

On a recent morning, her border collie, Noche, chased sheep, and geese flew across a grey-blue sky. Floyd's death changed her, she says: "I think it was a wakeup call, for sure. These issues can't be on the backburner. They are something we need to think about all the time."

Decorah, with its nearly-all-white population, has its own Black Lives Matter movement

Still, some complain.

A construction worker, asking me not to use his name, says he resents the way that store owners are asked to put the black-and-white "welcome" stickers in their windows: "Now, it's: 'Oh, I won't come to your business because you don't have a Black Lives Matter flag. Stuff like that."

But, as veterans of the movement know, change takes time, especially in a small town.

Guy Nave lives around the corner from his old house, in the neighbourhood where he was once told that he did not belong.

The town has a long way to go, but he sees a path, one forged with affection and concern for others.

"There is no way out of the degradation of racism, the pain, the injustice, without love," he says.

Later, he barbecued jerk chicken in his yard. Funk music played on a loudspeaker, in a neighbourhood that seemed, at least on that evening, welcoming to all.

Related topics

- Published14 April 2021

- Published9 April 2021

- Published9 April 2021

- Published13 April 2021