Adama Traore: How George Floyd's death energised French protests

- Published

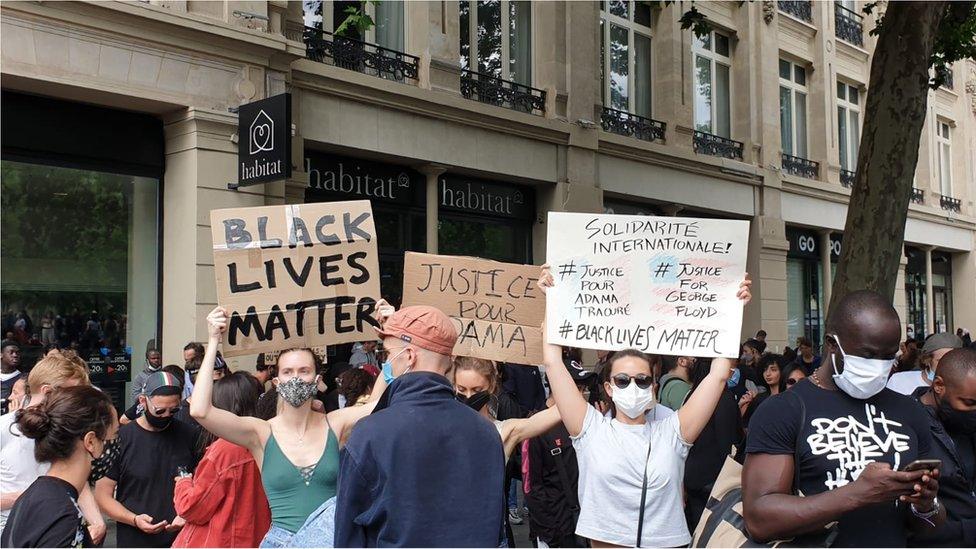

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd in the US last May, large protests erupted thousands of miles away in France.

Black Lives Matter banners aligned with France's own domestic movement organised under the slogan "Justice for Adama".

Adama Traoré was a young black man who died in French police custody in 2016.

Traoré, Amine Bentounsi, Remi Fraisse, Théo Luhaka, Cédric Chouviat. These are just some of the names of working-class victims of alleged police brutality in France, many of them black or Arab.

The movement dates back decades, with its earliest advocates from France's working-class suburbs, but there have also been more recent student protests in secondary schools. And the Gilets Jaunes movement - the yellow jersey protests against inequality - caused clashes with police that has led to growing concern in the mainstream over police tactics.

In the suburban town of Beaumont-sur-Oise, on the outskirts of Paris, Assa Traoré has become the symbolic figurehead of the movement in France, after her brother, Adama Traoré, died in police custody on his 24th birthday in 2016. No officers have yet been convicted.

Instead, Assa herself has found herself in the dock, charged with defaming the names of the officers she claims were responsible for her brother's death. In a letter "J'accuse", inspired by Emile Zola's historic denunciation of anti-Semitism in the infamous Dreyfus affair, she chose to name them.

Assa Traoré

"In America, Derek Chauvin was imprisoned to send a clear message that we do not accept this murderous behaviour," she tells the BBC's Clive Myrie.

"Well in France, no, we are experiencing a repressive response from the legal system."

The justice system is siding with the police, she adds. "It's shameful."

There is not footage of the death of Adama Traore, only the word of the officers present, against evidence the family and media organisations have reconstructed, a fact which has made prosecution in this case particularly complex. But activists against police brutality have for years relied on grainy phone footage to prove their allegations.

Shahin Hazamy, 25, calls himself a "ghetto journalist". He's from a working-class suburb and uses his Instagram to post videos of alleged police brutality which he and others from France's suburbs, have filmed on their phones. The images are shocking. Several show officers beating young men, seemingly without any provocation.

Shahin Hazamy films police making arrests

Others show the use of heavy handed force, neck holds and other controversial methods which have been linked to deaths in police custody. Shahin says his camera is his weapon: "We use social media to protect ourselves, to show people, the wider French population, how the police act with young people from the French ghettos."

He says the images of George Floyd's death resonated deeply with his own experiences. "Imagine if Floyd's death hasn't been recorded, none of this would have happened in France and the US, there wouldn't have been as much impact and justice wouldn't have come to pass."

"When I saw the video, I thought, that's exactly what we're living here in France. I can show you videos which are identical to the assassination of George Floyd, and they are happening in France."

George Floyd death: What’s changed, 100 days later?

But filming the police is set to get harder for young men like Shahin, with a new so-called global security law recently introduced. The bill initially sought to prohibit the filming of police officers, but even with amendments added that watered it down, human rights lawyer Arié Alimi says things will get tricky.

"The law hasn't changed when it comes to the right to film but it will change a lot on the streets, because people will be stopped a lot more when they get out their phones. The police are likely to believe that they can stop people who are filming them - journalists, citizens, especially when they are committing police violence or ethnic profiling."

What Article 24 in new law says

amended so the ban on filming police restricted to instances of deliberate attempts to "cause physical or psychological harm"

ministers say it stops calls for violence online against officers

but activists say it undermines police accountability

According to France's national ombudsman, young men of Arab and black African background are 20 times more likely to be randomly stopped by the police than the rest of the population, a statistic which Shahin says is rooted in institutional racism. He fears their only mode of defence - the phone - could soon be used against them.

Alimi says that without evidence to support an allegation of police brutality, cases are virtually impossible to prosecute. He represents several of France's most high-profile cases of police brutality, including the so-called "French George Floyd".

Four numbers that explain impact of George Floyd

Last year, 42-year-old delivery driver Cédric Chouviat was filmed as he repeated "I can't breath" seven times, while being pinned down by three police officers, and still wearing his scooter helmet. He later died. Three officers have since been charged with manslaughter.

"Should I, an average black man, be worried walking the streets of France?" Myrie asks Alimi.

"Yes, honestly, yes. You should worry about what could happen to you if you come across the police - there are even politicians, famous men and women, who are well known, who have been stopped and in some cases, experienced police violence in France."

The history of segregation in the US isn't the same as the history of colonisation in France, he says, but there is still a history of slavery, of colonisation, against Muslim populations.

"This history remains imbedded in the spirit of the policing institutions and means that you [Clive Myrie], when you walk in the street, you should be more worried than a white person."

Cedric Chouviat's family have called for the deadly chokehold, outlawed in many countries, and another technique also used on him, where a person is forced onto the ground face down while pressure is put on their upper body, to be banned. It was this latter technique which Assa Traore believes was responsible for her brother's death.

"By coincidence that day" she says, "the cameras in the police courtyard [where Adama's body was lying] were not working. But at my trial, an officer asserted that Adama wasn't even in the recovery position, confirming what the paramedics said. They left him to die like an animal."

So far the government has resisted reform, following pressure from police unions. This week, Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin appeared alongside police officers protesting outside the National Assembly, demanding for tougher punishments against those who attack officers.

His presence has been deemed a controversial one given he is in charge of the police, but also in light of shocking revelations this week. An investigation by news outlet Mediapart revealed that police officers had fabricated evidence in a high-profile case in which four police officers were among several hurt in Viry-Châtillon in 2016.

Police clash with protesters in Paris over new security law (from December 2020)

French police are among the most militarised in Europe - with deadly weaponry at their disposal, including LBD launchers known as "flash-balls" which have led to serious injury and even death, rubber coated bullets and grenades, which until last year contained TNT, a weapon banned everywhere else in Europe.

Most recently, a new law now allows off-duty police officers to carry their firearms while off-duty including in theatres and shopping malls.

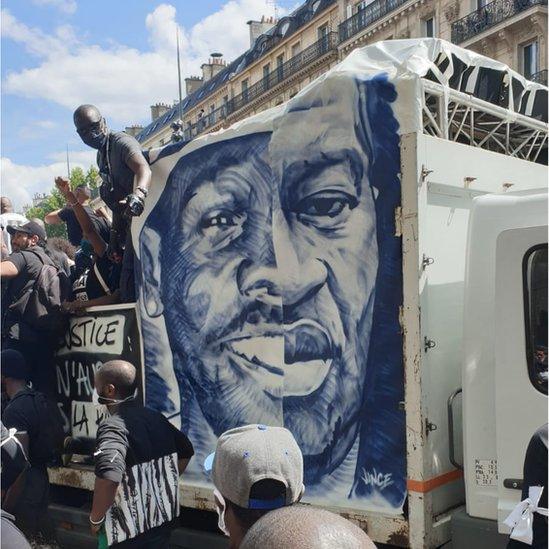

Half of George Floyd's face appears at a rally in Paris

While Floyd's death has in other parts of the world led to a reckoning with police violence and impunity, in France, new laws have so far increased police power.

Police trade unions say this is necessary given the tough conditions they face.

Jean-Christophe Couvy leads one of the biggest police unions, Unité SGP Police.

He recognises that the scaling back of community policing over several years has been a disaster, rupturing relations with those they're supposed to serve: "This generation for us, actually is lost - we think we've lost a generation - but we want to fight for the next generation. This is a generation which is very violent, there is a lack of values, they need to be less violent, perhaps they need more education."

He denies racism within the police force, saying: "if we have some racist policemen in France, they tarnish the rest of the police. For us, they need to get out. We are here for the people - black, white, Asian, Arabian".

As part of this investigation, the BBC contacted Prime Minister Jean Castex and the interior minister but both declined to comment.

Activists believe this is a pivotal moment for France, and her failure to stand up for its citizens could doom not just this generation, but also the next.

President Macron's promise on taking office, of creating a new compact between the police and the public seems a distant memory. With the 2022 elections looming, security remains one of France's central concerns. But for those in working class neighbourhoods, the question is whose security is being prioritised.

Myriam Francois is a journalist and writer based in Paris and London, and the host of the We Need to Talk about Whiteness podcast?

- Published3 June 2020

- Published5 December 2020

- Published5 December 2020

- Published6 December 2018

- Published9 June 2020