Tulsa massacre: The search for victims, 100 years on

- Published

A hundred years after white mobs rampaged through an affluent black neighbourhood, the search for bodies is a deeply personal mission for one scientist.

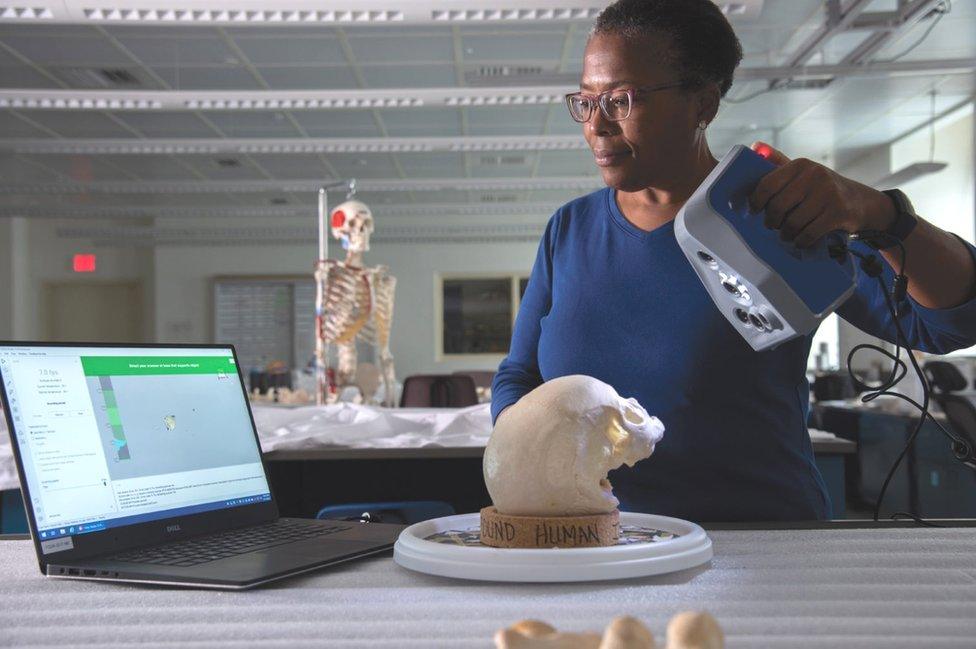

"My job," says Dr Phoebe Stubblefield, "is to let the bones speak."

Now the forensic anthropologist is at the forefront of the search for victims of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre.

It is a professional - and a personal - mission for the research scientist at the University of Florida.

"There are not very many black forensic anthropologists," she says. "For Tulsa, it's this rare chance of let a black person use black bodies to tell their story."

As the centenary of the Tulsa massacre approaches, it remains one of the worst incidents of racial violence in US history.

Against a backdrop of racial segregation, Ku Klux Klan rallies and lynchings, on 31 May 1921 armed white mobs went on the rampage in the prosperous black neighbourhood of Greenwood.

Dozens, if not hundreds, were killed. Thousands were injured. Homes and businesses were looted and burned to the ground. Within 16 hours the area had been obliterated.

Dr Phoebe Stubblefield has been working with historians and archaeologists to try to find the bodies of the victims since 1998.

It has been a slow, painstaking and often frustrating process. Searches failed, but finally, two years ago, they identified an area of Oaklawn Cemetery in north Tulsa near the Greenwood area where the massacre took place.

Ground-penetrating radar was used to survey the site. And in October 2020 they hit a mixture of wood and bone.

"We had hit an area of coffins. While we were just trying to dig over them we exposed a little bit of cranium material...and I saw that and I said 'we've found a man's burial. I think we've found them'."

They discovered 12 wooden coffins, each laid side by side, containing human remains. But scientists think more bodies could be concealed there. This was not just a burial pit. It was a mass grave.

Dr Stubblefield had hoped to examine the human remains in the coffins at the site. But they are fragile and the decision was taken that analysis needed to be carried out indoors, in a climate-controlled laboratory.

The bodies will now be exhumed in June. When she comes to study them, Dr Stubblefield says she will be looking for "evidence of gunshot wounds or bullets or lead scatter inside the skeleton" to help determine if the remains are the result of the massacre.

Back in 1921 many of the victims died from gunshot wounds, she says, and because there were no post-mortem examantions, there's a good chance the bullets will still be there.

In 1921 Tulsa saw one of the biggest race massacres in American history.

Dr Stubblefield adds that for her, "ultimate success" would be memorials "with names attached to the individuals, with a thorough record of, as bad as it is, what their last moments were like. That's my best case".

But she fears the "direct identification" of victims may not be possible, although the descendants of victims could be found by analysing DNA extracted from teeth.

Dr Stubblefield is certainly prepared to try. "My work is the story of someone's loved ones."

For decades, the story of the massacre was largely erased from history. Official records were lost or destroyed, the city's newspapers did not mention it, schools did not teach it.

Even many who grew up in Tulsa were unaware of what had happened.

Dr Stubblefield's parents were born there but they never spoke about it, even though her great aunt lost her house in the attack.

"Race massacre: no discussion whatsoever," she says. "A lot of bad things just weren't discussed.

"I think it was on the list of, why live in the past?"

And facing up to that past has been no simple task.

"Oklahoma itself tried so hard to hide this event, let's reverse it fully by memorialising these people correctly," she says.

The centenary of the Tulsa race massacre will be marked on 31 May with a series of events, including a candlelit vigil and a memorial service.

The televised event promises to include celebrities and there has been speculation Vice-President Kamala Harris and former President Barack Obama and his wife Michelle could attend.

A new book by the award-winning historian Scott Ellsworth - The Ground Breaking, The Tulsa Race Massacre and an American City's Search for Justice - is also being published to coincide with the anniversary.

The professor of history at the University of Michigan has played a key role in identifying and locating potential burial sites. And he says the search will go on.

"I'm extremely confident that massacre victims were buried in at least three other locations. We have an eyewitness for one, we have very strong evidence from both the black and white communities about another area and we have a good oral tradition on the third.

"The problem is to do with the deterioration of bones... that depends on soil acidity. So this is going to take a while. But I'm confident they are there and I'm hopeful that eventually we will find them."

And Dr Stubblefield will be with him every step of the way.

"I can certainly keep searching for multiple individuals killed in an event like the Tulsa race massacre," she says, "because that's what I do."

You may also be interested in

Kimberly Jones explains her viral Monopoly analogy: "How can you win when you've been stripped of everything?"