NFL: How race-based formulas are interfering with concussion lawsuits

- Published

Najeh Davenport accuses the NFL of discrimination in calculating compensation

The National Football League has promised it will no longer settle concussion lawsuits using race-based formulas that assume black players have lower cognitive function. Why was it using them to begin with?

In 2013, the NFL agreed to a multimillion-dollar settlement with retirees who alleged their on-field concussions had given rise to brain injuries and cognitive disorders like dementia.

It has now awarded more than $856m (£600m) to compensate victims and pay for their medical exams.

But several former black players say they have received nothing in spite of their concussion-related diagnoses. The vast majority of NFL retirees are black.

They blame the settlement programme, which applies a binary standard - known as "race norming" - that assumes the average black player has a lower level of cognitive functioning than the average white player, and adjusts their cognitive test scores accordingly.

As a result of the race norming methodology, they allege, black players must demonstrate greater levels of cognitive decline in order to be eligible for a payout.

America's top-tier football league has defended its use of the scoring adjustments, pointing out the standards were originally established with the aim of correcting racial bias.

What's the history?

Race norming was first used roughly 40 years ago, to forestall racial bias in aptitude tests.

Aptitude scores in federal job applications were adjusted to account for the test takers' race and ethnicity, a policy first implemented under the Democratic administration of Jimmy Carter, extended under the Republican administration of Ronald Reagan and even adopted in 38 US states.

It was outlawed at the federal level by the Civil Rights Act of 1991, but race norming was by then seen as a means of counteracting racist practices.

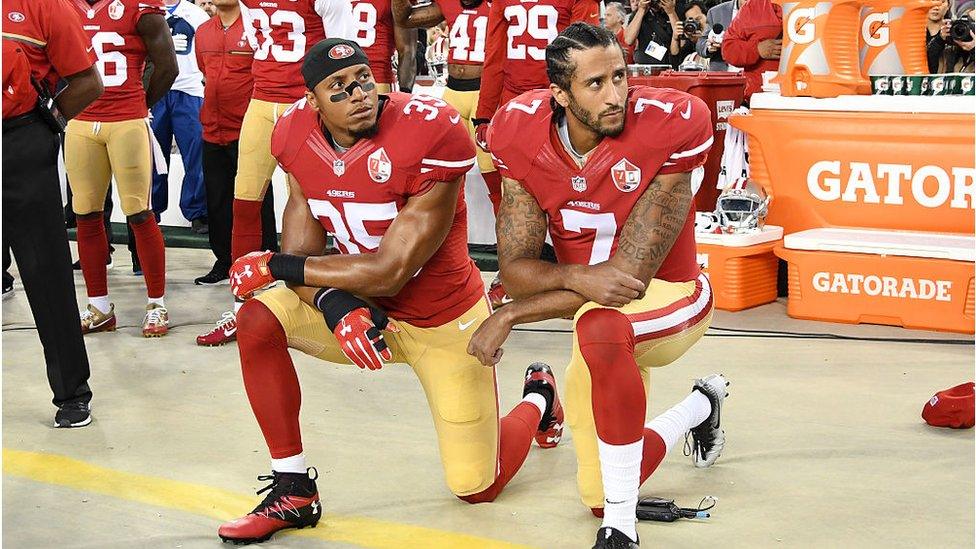

Colin Kaepernick (right) led protests over alleged police brutality

Before its use within the NFL settlement scheme, the standard has been used in a variety of medical applications.

"Being black in this country is associated with all kinds of disadvantages: less education, more childhood adversity, less access to healthcare and so on," explained Dr Katherine Possin, a neuropsychology professor and researcher at the University of California - San Francisco.

"If you ignore that somebody comes from this more disadvantaged background, then you'll diagnose complex disorders more often in that person."

Within her field, she said, the practice of race norming was "a band-aid solution that didn't come out of a desire to be racist". Instead, it would prevent clinicians from "over-diagnosing and over-pathologising cognitive impairment in black people".

How does the NFL use it?

In the early 1990s, neurologist Robert Heaton developed a system for making race-based adjustments in cognitive test scores.

His methodology revolved around black and white Americans, and relied on a small homogenous sample of black people from the military town of San Diego, California.

The "Heaton norms" appear to have formed the basis of determining the size of payouts from the NFL's compensation scheme.

Clinicians who are part of the programme receive a manual that calls for a "full demographic correction" of the player's cognitive test scores in line with the "norms" for their age, gender, level of education and race.

"It's a 'plug and play' formula that determines whether someone scores low enough to qualify for an award," said Dr Possin. "With the demographic corrections that are part of this formula, black players have to score lower than white players."

The formula leaves little room for the doctors to make clinical judgments, based on the person sitting in front of them, according to Dr Possin.

Why is the NFL under fire?

Critics allege the NFL, a sports league that long denied the links between on-field concussions and cognitive issues, has used race norming as a means of depriving retirees of compensation.

The NFL's concussion settlement website reveals hundreds of denied claims, although the race details of claimants is not mentioned.

One retiree, Najeh Davenport, claims the NFL appealed his dementia diagnosis because it was not race-normed, leading to an adjustment that reversed his diagnosis and prevented him from receiving compensation.

Mr Davenport and another player, Kevin Henry, filed a civil lawsuit against the league last August alleging it was potentially discriminating against thousands of their peers.

Their case was thrown out, but the judge has asked for a full report on the score-adjustment issue.

The league has defended itself by arguing the settlement scheme was developed "with the assistance of expert neuropsychological clinicians" and "relied on widely accepted and long-established cognitive tests and scoring methodologies".

In a statement on Wednesday, it pointed out the manual does not require clinicians to adopt the racial binary in their diagnoses.

Clinicians have disagreed, although few have spoken out publicly on the issue. In one private email obtained by ABC News, a doctor involved in the program bluntly writes: "I don't think we have the freedom to choose. If we do, apparently many of us have been doing it wrong."

Growing legal pressure and media attention on the issue may be prompting a shift.

On Wednesday, the NFL issued a statement pledging to halt the use of race norming, make retroactive payments to players impacted by the policy, and develop new testing protocols in concert with a panel of experts that includes black doctors.

No major neurological organisations have weighed in with policy statements about the appropriate use of race norming, but Dr Possin hopes the NFL case will prompt a move toward more precise approaches that consider a person's lived experience.

"One danger to the continued use of race norms is it perpetuates a false idea that there are genetic differences in intelligence that fall along race lines and that's simply not true," she said.

"There are differences on average between blacks and whites because of differences in social experience."

Related topics

- Published3 June 2021

- Published28 May 2018

- Attribution

- Published5 June 2020

- Attribution

- Published6 June 2020