A Pride symbol vandalised in Canada's 'prettiest little town'

- Published

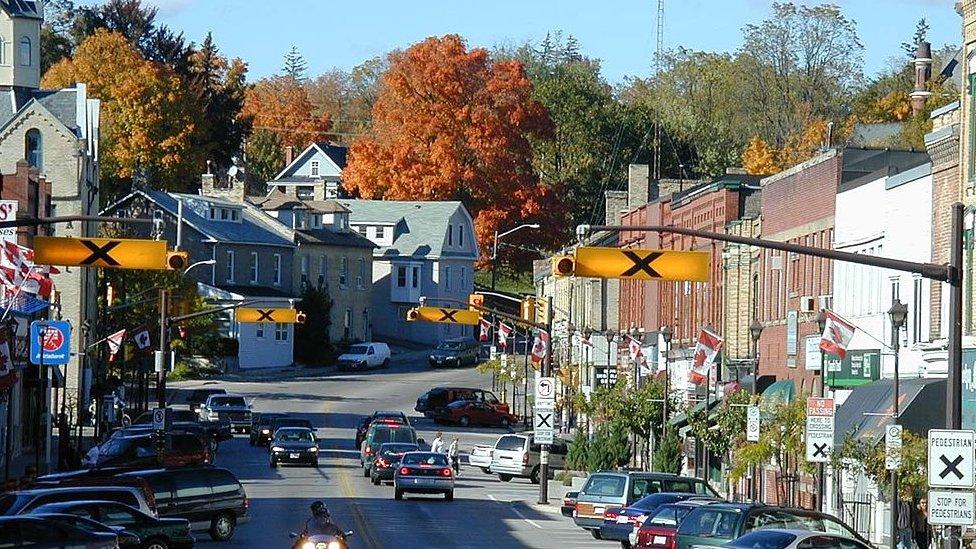

Paris, Ontario bills itself as one of Canada's prettiest towns

It took one night for a Pride rainbow pedestrian crossing on the busiest street of Paris, a small Canadian town just over an hour's drive from Toronto, to be smeared with burnt rubber. Was a rainbow a bridge too far for the town, or is a new era of progressive politics forcing Paris to change its stripes?

Dotted with Carolinian foliage, church spires and cobblestone architecture, Paris wears its unofficial tagline - 'Canada's prettiest little town' - proudly.

It's one of dozens of smaller Canadian communities growing in popularity as people desert big cities during the pandemic.

Nathan Etherington, 39, who spearheads Pride celebrations in Paris, calls the town "literally a microcosm of Canada" - a rural area near urban centres, with a large First Nations reserve nearby.

He was thrilled when the rainbow crossing passed 10-1 before council.

But his elation was short-lived: there have been several reports of vandalism on rainbow crossings elsewhere in Canada.

Paris's damaged Pride pedestrian crossing

In Elgin County last year, about 100km (62 miles) south-west of Paris, two young men were charged with mischief after spinning their tires across a rainbow crossing.

In Aurora, 160km north, police laid mischief charges over acts of vandalism - including spray painting - on another crossing.

So Etherington says he knew something could happen to the one in his town.

"I had already moved past it before [the vandalism] had even occurred," he says.

Placing the crossing on Paris' busiest road came with a risk, Etherington admits, but he says "symbolism matters".

"That's really what the crosswalk has become - it's a symbol of the discussion that needs to happen," he says.

Police confirmed they are treating the vandalism in Paris as a "mischief case", and are pursuing several leads.

The crossing has been vandalised and repaired twice since it was installed last month.

The idea for the crosswalk came from Brant County Mayor David Bailey, who campaigned for office as an openly gay man.

Bailey, a lifelong resident of the municipality, says he still remembers his teenage years, when "we were hiding, we were going to clubs through back doors, and we were getting eggs pelted at us".

Nathan Etherington spearheads Paris Pride celebrations

In Canada, homosexuality was decriminalised in 1969.

"When I was 16 years old, when it was 'illegal' to be me in my own country, I was trying to figure out life in a small town, knowing that I really wanted to stay there but knowing that, unless you moved away, you couldn't be yourself," Bailey remembers.

"And now, I'm the first elected openly gay mayor in Ontario," he says.

(The mayor of Canada's national capital Ottawa, Jim Watson, revealed in 2019 that he was gay, after spending much of his adult life in public office. Canada's first openly gay member of Parliament came out publicly in the late 1980s.)

Bailey says he doubts whether he would have been elected 10 years prior to his appointment in 2019. "My time was now," he says.

But, today, he says, "there is nothing homophobic about the County of Brant".

"There's always that handful of people who throw rocks at everything, that just don't like change. But Paris and the County of Brant have come a long way."

Paris has been grappling with the influx of new blood, exacerbating a decades-long divide between the long-time locals and the people who want change.

Bailey says his municipality is seeing a shift in diversity among residents that goes beyond sexual orientation.

"The face of Paris and the County is going to change dramatically in the next few years," he says.

He says it's not going to be easy for the municipality to accept all the changes "but they will accept it... because they're wholesome, healthy, friendly people".

Etherington was born and raised in Paris in a "very right-wing, Christian, Pentecostal" family and says as a child there was "no support, no comfortable place for me".

When he was 20 years old and working at a fast-food restaurant, a customer called him a homophobic slur.

"I went to the back room and cried for about 30 seconds, then the anger took over and I went back to the front window. I said, 'how dare you come in and discriminate against me in my workplace? I wouldn't do that to you'.

"And that's when he threatened to get out of the car and beat the daylights out of me. His wife stopped him."

But Etherington has felt the tide change in Paris since that incident almost two decades ago.

These days he feels wholly supported as an openly gay man, something about Brant County "which is really worth preserving and protecting", he says.

Local support for Pride in Paris

In the aftermath of the vandalism, Facebook community groups - the pandemic's answer to town halls - have been abuzz.

One person posted that a child they care for, who identifies with the LGBT community, said seeing the rainbow crossing had "made their day".

"That makes an impact that overwhelms all the hate, knowing that one young person has something that you never had growing up," Etherington says.

He has contacted around 18 people who left comments saying their Pride signs had been stolen from outside of their home.

"We had to have a vandalism strategy… So far, I've been able to replace every single sign that people have reported," he says.

The response in Paris has overwhelmingly been one of empathy. Several local churches, businesses and individuals have already volunteered enough funds to repair the crosswalk many times over.

Not everyone liked the idea of the pedestrian crossing in Pride colours on the busy street.

Local mechanic Justin Quarters, 29, argues its placement on "the absolute easiest spot to be vandalised was just asking for trouble".

Rhonda Garnier, 52, a primary school principal, lives in Paris with her partner Cathy Garnier, 55.

Initially, Rhonda also questioned having a rainbow crossing, thinking it was simply cosmetic when compared to things like helping underfunded help lines and support groups.

But after the vandalism, Rhonda changed her mind.

"It served as a really nice barometer for Paris. It allowed the hate to come to the surface and be smacked down, for a line to be drawn in the sand," she says.

Rhonda and Cathy Garnier were initially sceptical about the crossing but now support it

Rhonda says the community of Paris has welcomed her with open arms during the past decade, but she does "wonder everyday, when you leave the house, if something's going to happen".

Cathy says she checks each morning to see if their "Love is Love" sign is still in their yard, or if someone vandalised their property.

In 2019, police reported 263 hate crimes targeting sexual orientation countrywide, up 41% from 2018, according to Statistics Canada, the federal statistics agency.

It was the highest number of hate crimes targeting sexual orientation dating back to 2009.

But Cathy says of the perpetrators in Paris: "We don't know if they're just kids who just want to be little jerks."

Bailey says those responsible are likely uneducated and stressed by the pressures of the Covid lockdown in the province.

Rhonda agrees.

"Do I think the person who defaced that is hateful? No - I just think they're stupid," she says. "That's not who we are anymore."

"Sometimes I think the last dying breath of hate comes out in these moments, and I choose to believe that's what this is."

You may also be interested in:

Watch Andi's remarkable journey: 'I can finally be who I've always been'

- Published27 June 2021

- Published25 June 2021

- Published28 June 2021

- Published12 June 2021