Fire lookouts: The US Forest Service lookouts watching for fires

- Published

Many of us struggled to adapt to home working and isolation during the coronavirus pandemic. But the few remaining fire lookouts of the US Forest Service often live and work for weeks at a time on their own, scouring the horizon for any hint of smoke from remote lookout towers.

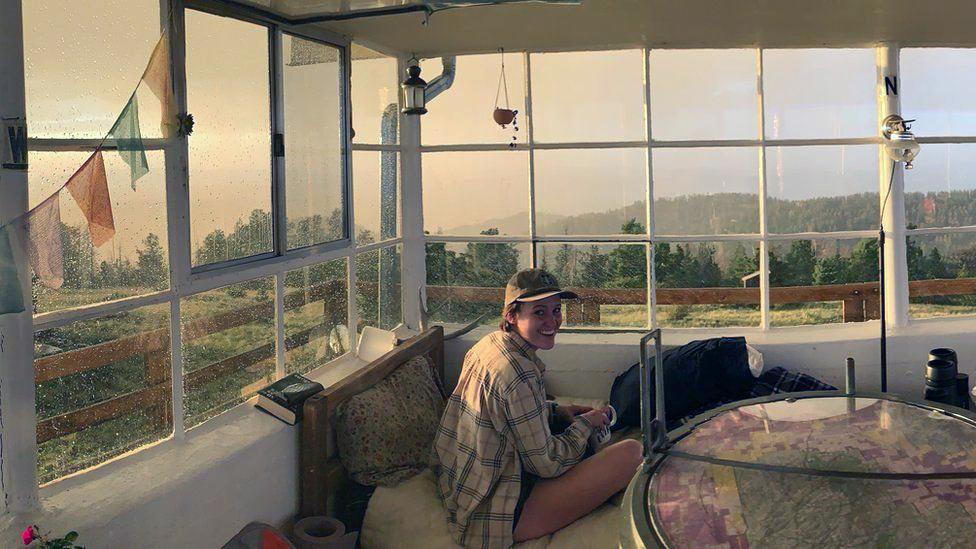

Kelsey Sims was at home in Ohio at the start of the pandemic. The 26-year-old had previously worked as a firefighter, spending two years on fire engines in wild areas of Montana, but had recently lost her job and had no idea what to do next.

"I applied and got a job here in New Mexico," she says, on the phone from her lookout tower in the south-western state. She flew out just as states began to impose strict measures to combat the spread of Covid.

"It was extreme restrictions on everything, and then I got here and I was literally alone," she says. "The pandemic really didn't hit me - I'm so blessed not to have dealt with it in ways other people have."

The fire season in the area begins in March or April and continues until early October, sometimes even later. Fire lookouts in the region can work long hours when the risk of fire is high - six days a week, for 10 hours at a time, all through the season.

"You can't really have a social life as a fire lookout," she says. "But I think most people know that going into the job."

Like many lookouts, Kelsey lives in her tower. There's no electricity or running water, and her lights and cooking equipment run on propane gas - "nothing super fancy," she explains. She has to bring all the food, water and supplies she needs up to the tower on her day off for the week ahead.

Kelsey Sims became a fire lookout as the Covid pandemic broke out

She lives and works in her tower six days a week during the peak fire season

On a typical day she wakes up five minutes before starting work at 07:00. "I only have to commute a foot," she says. She takes mornings slow, scanning the horizon and eating her breakfast before joining her colleagues on a video chat at 09:30. They discuss weather, staffing, and the fire situation - where there are blazes in the state and across the US. She keeps her tower clean in case any hikers visit. It's a historic lookout, built in 1952, and part of her job is to teach people about fire safety and prevention in the area.

"My mom doesn't really understand it," she says. "But if you're comfortable with yourself this is honestly the most peaceful job in the world. It's the most pure form of solitude imaginable."

When she's not working she makes TikToks about her work as a lookout, external, educating people further afield about the job. She recently got a dog called Roo to keep her company, and to pass the time she's teaching herself to cook and to play the bagpipes.

Kelsey has a new dog, Roo, and explains her work on her TikTok channel

Otherwise she spends her long days scanning the horizon for signs of fires - smokes, as the lookouts call them - and calling them in to colleagues, who despatch firefighters in engines and helicopters to tackle the blaze.

The equipment is elementary. Lookouts have a radio, binoculars, and an Osborne Fire Finder - a device used to determine the location of a smoke. The circular device features compass points and two sights. This allows lookouts to determine an azimuth, the term for a type of compass bearing, to mark the location of the smoke.

No lookout tower can be without one, explains Laura Rose, who works in Arizona's Prescott National Forest. Like Kelsey, Laura works six days a week through the season, although her tower is close enough that she can drive home each night.

"My lookout was built in 1936, and you basically do the job exactly the way you did it in 1936. Isn't that incredible?" she says.

The Osborne Fire Finder was invented decades ago to locate forest fires

US Forest Service lookouts still use the device to this day

Laura is in her third season as a lookout. At first, she struggled with the work. She has spent decades with the forest service, often doing physical jobs with lots of walking. Now, she works alone in the tower, without much space to move.

"This is a job where you're just looking, and not doing something physical - even with your hands," the 63-year-old says. "It was kind of anxiety-inducing at first."

But though the tower interior is only about 11ft by 11ft, it doesn't feel claustrophobic. Large windows and stunning views of nearby Spruce Mountain make Laura feel like she's in nature. She quickly settled into the role.

"You feel like you're on a perch," she says. "You don't feel like you're penned into a space or anything because the mountain is almost 8,000ft. It really has a big view of an excellent landscape."

And while she admits it can feel lonely, she has adapted to the solitude. "It does have a bit of an isolated feel to it. But I'm fine with it, it's not something that really bothers me."

Laura Rose is in her third season as a lookout

Her tower is in Arizona's Prescott National Forest

Laura believes she's spotted about a dozen blazes each season she's worked. Monsoons in the state bring electrical storms which can set off plenty of fires, with lightning firing out from the edges of the rain columns - meaning the water doesn't always quench the flames.

As someone who has worked in forestry for years, she has trained others at lookouts. "When I see a smoke I know a smoke," she says. "Trust your eyes, trust yourself."

This year is Reza Fakhrai's first fire season, and he's already managed to spot two smokes. The first, he says, was obvious. It tripled in size on its first day of burning, turning into a 700-acre fire. "That was kind of a no-brainer type of smoke," he says.

But the second was harder to spot. Reza's lookout oversees Santa Fe National Forest in New Mexico, with views as far as the mountains in Colorado to the north. This means smoke from fires in other states can drift over, obscuring visibility.

"I had to study that [second] smoke quite a bit through binoculars and eventually convinced myself that it was definitely a smoke that needed addressing."

Reza's lookout oversees Santa Fe National Forest

It has views as far north as Colorado

Firefighters managed to reach it within an hour and a half. On the radio they told him it was about half an acre in size, so they were able to quickly put it out. "It was a timely call, I guess," Reza says. "It's one of the many fires that's burning out here - they're not the big huge ones like in California, but they're certainly an ongoing problem."

In the last few years wild fires have ravaged huge areas of California, killing dozens and wiping towns off the map.

Scientists have blamed climate change for their growing prevalence and intensity. But they have also highlighted forest management as an issue: the need to clear dead trees and even to burn small areas in a controlled way to create fire breaks and prevent even greater, more destructive blazes.

As Reza talks on the phone, describing his views over the surrounding country, a 6,000 acre fire is burning to his east. Lightning ignited the forest about four weeks earlier, and authorities are managing that blaze instead of trying to fully suppress it.

"When we get an opportunity, when it's in favourable terrain and when we think we can handle, they choose to manage a fire," he says.

Authorities try to manage some forest fires, to prevent even greater burns in later years

While on duty Reza starts his days training with fire crews in the town of Cuba, before driving up to his post. Unlike other lookouts, Reza doesn't live in his tower - the 34-year-old stays in a travel trailer nearby while he's working, and on his one day off a week he drives back to Albuquerque to see his wife.

Reza previously spent 10 years working as a geologist in the oil and gas industry - a corporate job, following in his father's footsteps. But he had always had a desire to work outdoors with natural resources, and thought now was the time to take the job before new technology closed the remaining lookouts.

"We are being replaced, for sure," he says. Satellites can detect heat and flames on the earth's surface, while drones and aircraft can fly around and grid a certain area or look for smoke from the sky. "So there are a lot of replacements for lookouts," he said.

States across the US are closing fire lookout towers as new technology comes in, transforming some into accommodation. In New Mexico, the forest service has in recent years deployed drones, external to monitor blazes. And while there were once thousands of lookouts and towers across the US, now there are far fewer - the state of Wisconsin closed its last 72 lookout towers, external in 2016, for example.

But there remains a place for people on the ground looking out for fires. Lookouts know the terrain; they can help direct firefighting resources from their towers by radio. And by the time satellites detect fires they sometimes have grown too large, leaving authorities with fewer options to control them.

Reza has an even simpler explanation for why the job still exists. "I think the reason why they keep us around is because in the end we always end up being much cheaper - and that's really the name of the game in the federal government," he said.

Reza wanted to become a fire lookout "before the time is really up"

His wife has been extremely supportive of him taking the job. "She followed me around for my previous career in oil and gas and I think she saw the toll that that job took on me mentally and how it maybe just wasn't the best fit for me," he says. Raised on books by environmental advocate Edward Abbey and US naturalist Henry David Thoreau, he got the itch from a young age to do something outdoors - "something that's a bit out of the ordinary," he says.

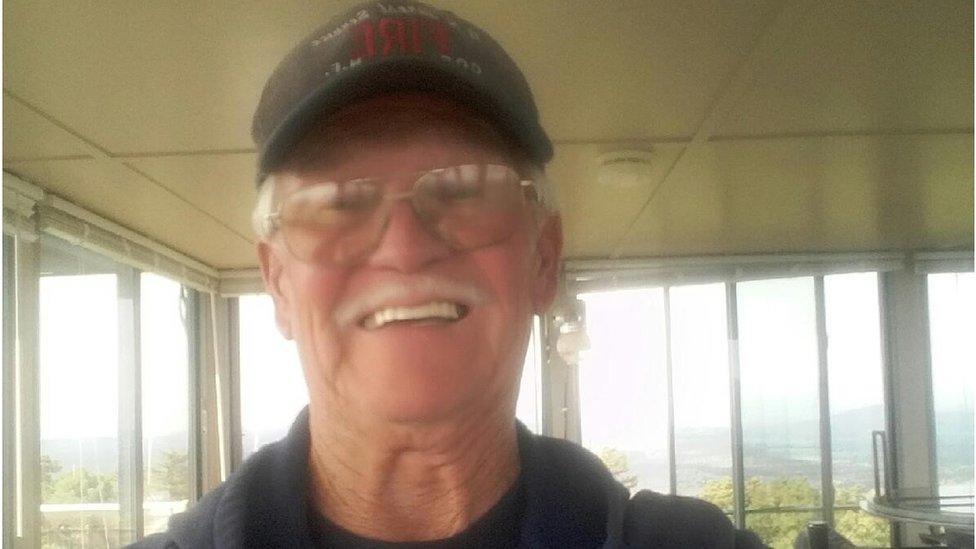

As a young man, Don Slocum trained as a dental technician. "Making crowns and bridges," he says, on the phone from his lookout tower in Arizona. But despite graduating, he realised that was not the career for him. "I'm kind of an outdoors guy," he says.

After a stint in the army Don spent 22 years as a park ranger in the US. One day, roasting in 46C (115F) weather on a desert lake patrol boat, he looked high up at a lookout tower and thought it looked like a nice job. "A little cooler, perhaps!"

The 76-year-old is now in his 14th season as a fire lookout. His tower sits 7,300ft high on Apache Maid Mountain in Coconino National Forest. He describes it as the "Cadillac of the lookouts" - built in 1961 but remodelled in the last decade. A previous tower he worked at was just a seven foot by seven foot box, that did not feel well prepared for winds and rains on the peaks. "I used to joke with people, if it's blowing to the right, we move to the left!"

Like Kelsey, Don lives in his tower - six days a week, ten hours a day, for months and months at a time. "It's lonely at the top, so to speak!" he says. To pass the time he likes to read, and to practise on the Osborne Fire Finder. "I start what we call shooting azimuths, to keep the skill level up mentally," he says.

This is Don's 14th season as a fire lookout

Like Kelsey, Don lives in his tower six days a week - so he has to lug food, water and fuel up with him

His wife Patricia - who he drives down to see on his days off - understands his love of the job. Working at the lookout with views far out over the varied landscape is almost a religious experience for him. "I wish I could articulate the reason - when you're up in this lookout, there's something," he says.

A lot of his lookout friends are in their 60s and 70s, a similar age to him. Some are retired teachers, while others are younger, college students looking for something different - "a hodge-podge of different people", he says.

Don describes lookouts as "a dying breed of people", and expects new technology will render the last few fire lookouts obsolete in the years to come. But people still ask him about the job and how they could get into it.

"A lot of times a wife will come up with her husband," he says. "And she asks, I want to get my husband out of the house for five months, what's he have to do to apply for it?"

All photos subject to copyright.

Related topics

- Published18 April 2021

- Published23 October 2020

- Published25 September 2020

- Published17 November 2019

- Published3 September 2020