Why Canada is reforming indigenous foster care

- Published

Christine Miskonoodinkwe-Smith has reconnected with her indigenous culture

The revelations that there are hundreds of indigenous children buried in unmarked graves at the sites of former residential schools have shaken Canadians. They have also increased calls for changes to the country's foster care system, where indigenous children are vastly overrepresented.

Christine Miskonoodinkwe-Smith, from Peguis First Nation in Manitoba, was taken by child services when she was about a year old, along with her sister, and adopted by a non-indigenous family in the province of Ontario.

The loss of family and cultural connections can be devastating to children in care.

"Not knowing your culture just drives an anger inside you," says Miskonoodinkwe-Smith, who is of Saulteaux descent. "It separates you from your very own identity in a way, because you have to live in two worlds. You're living in a non-indigenous world, but then you know there's another worldview, which is your culture."

Her adoptive parents eventually became emotionally and physically abusive and gave her up when she was 10, but kept her biological sister. She spent the rest of her youth with other non-indigenous foster families and in group homes.

She didn't get a chance to learn about her culture until her 20s.

"Once I started going to pow-wows and cultural events, it really made me change inside," said Miskonoodinkwe-Smith, now a writer living in Toronto.

"It made me more aware of the issues around what indigenous people have been through."

The grim discovery of approximately 215 children found buried in unmarked graves at the site of a former residential school near Kamloops, British Columbia in May, and similar discoveries at other sites like at the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, has brought renewed attention to the treatment of indigenous children in Canada.

Unmarked graves were found at the site of the former Marieval Indian Residential School on the Cowessess First Nation

Residential schools operated for over a century, part of an historical programme to forcibly assimilate indigenous youth into white society.

Many campaigners are now highlighting the links between that system and the estimated 40,000 indigenous children and youth in foster care, according to figures from the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), a national advocacy organisation.

Census data shows that more than half of the children in Canadian foster homes are indigenous, despite them making up less than 8% of the country's child population.

The child welfare system is run primarily by individual provinces, and the figures vary. In Manitoba, approximately 90% of children in care are indigenous.

Concerns about Canada's foster care system, and the unjust treatment of indigenous children, are not new.

For over two decades, Cindy Blackstock, an activist and member of the Gitxsan First Nation, has fought for the rights of indigenous children in care.

Cindy Blackstock has fought for the rights of indigenous children for decades

"The reasons why indigenous kids go into care are driven by poverty, poor housing, substance misuse and mental health and domestic violence, due to the multi-generational trauma of residential schools," says Blackstock, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society.

Blackstock has led successful legal battles for reforms to the system - and is still fighting Ottawa over the compensation for those affected by on-reserve child welfare practices.

What are residential schools?

The removal of children from indigenous homes has been a part of Canadian life since its early days as a European colony. By the late 19th Century, it had become government policy.

Beginning in the 1880s, some 150,000 First Nations, Métis, or Inuit children were taken away from their families to be placed in residential schools. The last of these institutions closed in 1996.

A landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which delivered its final report in 2015, found that sexual and physical abuse at residential schools was widespread. It estimated that at least 4,000 indigenous children died in those schools, mainly from disease or malnourishment.

The disproportionate removal of indigenous children by welfare agencies was part of the legacy of residential schools, which deprived their pupils of positive parenting, self-worth and a sense of identity, said the TRC.

"Children who were abused in the schools sometimes went on to abuse others," the commission wrote.

"Many students who spoke to the Commission said they developed addictions as a means of coping. Students who were treated and punished like prisoners in the schools often graduated to real prisons."

As the residential school system was wound down in the middle of the 20th Century, new child welfare policies were enacted that allowed government officials to take thousands of indigenous children into care, with little or no warning to their families.

This period, which lasted into the 1980s, has become known as the "Sixties Scoop".

Canada's "Sixties Scoop" saw indigenous children taken from their families. Now survivors are mapping out their stories

Although it was curtailed with new regulations, and a greater emphasis on indigneous-led child welfare agencies, the disproportionate flow of indigenous children into the foster care system has continued.

Canada's minister of indigenous services, Marc Miller, says there are now more indigenous children in care across the country than were ever in residential schools at any one given time.

Racism in the modern child welfare system has been well-documented and systematic, he says.

That could include officials applying rules inconsistently in a way that negatively affects indigenous people, or a refusal to let indigenous children engage with their culture.

What's being done?

The goal for child welfare officials should be to give indigenous families the help they need to keep their children in spite of any challenges they may face, says Jeffrey Schiffer, the executive director of Native Child and Family Services of Toronto, an indigenous-led agency providing culture-based programmes.

"After decades and decades of families being torn apart by systems of residential schooling and later foster care, it is so important that we provide circumstances in which families can stay together, and learn about indigenous culture and language, '' he says.

Only 3% of the calls the organisation receives result in a child being removed from their parent or guardian, says Schiffer.

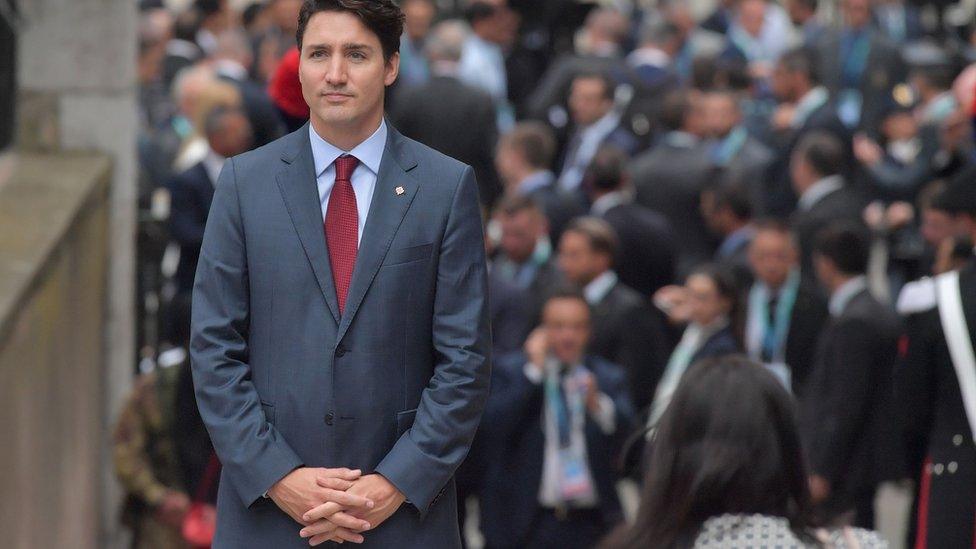

Prime Minister Trudeau, with Chief Cadmus Delorme, visits the site where Cowessess First Nation found hundreds of unmarked graves

When a child is removed, the focus is on trying to place them with extended family or community members.

The federal government must also fix widespread social problems that lead to situations in which children are removed from their parents, Blackstock says.

Indigenous leaders point to high child poverty rates, higher than average suicide rates, and chronic infrastructure problems with water and housing on reserves as key issues.

The Liberal government has worked to increase funding for indigenous youth since Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took power in 2015, says Miller.

"It isn't the end of the story, but it works towards moving that system away from the heavy hand of the law, to one that is really lifting up prevention alternatives."

There are some other slow changes taking place.

Cowessess First Nation made the recent discovery of approximately 750 unmarked graves at the site of the former Marieval Indian Residential School.

On Tuesday, it signed a multimillion dollar agreement with the federal and provincial governments that would give the First Nation management over child and family services, which Chief Cadmus Delorme said will reflect "our culture, values, and priorities".

That partnership was possible due to new legislation - passed in 2019 - affirming indigenous peoples' right to enact jurisdiction over child and family services in their own communities. Cowessess is the first to ink such a deal under the law.

At the formal signing ceremony, Delorme said: "The end goal is one day, there will be no children in care."

Related topics

- Published15 July 2021

- Published24 June 2021

- Published27 May 2017

- Published6 June 2021