Afghanistan: What's the impact of Taliban's return on international order?

- Published

The Biden administration's rush for the exit in Afghanistan has been accompanied by a similar rush to judgement among pundits and commentators who, by and large, have castigated the US president for a decision that many see as unnecessary and a betrayal, both of those who served in Afghanistan and of the Afghan people themselves.

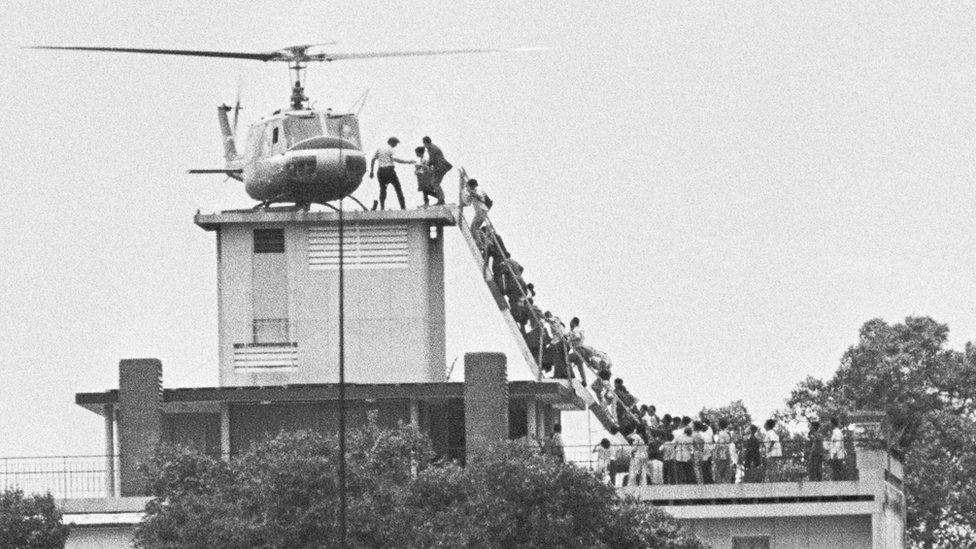

The heartbreaking images from the airport in Kabul only reinforce this message. And there is justifiably a good deal of emotion to go round. The West has invested a lot of blood, time and money in Afghanistan. The Afghan people, much, much, more.

It is hard to argue with the criticism of the Biden administration's precipitate departure. Afghanistan may indeed be un-salvageable, its governing structures too unrepresentative and corrupt. This though only underscores the argument that Afghanistan was not "lost" in the past two years but during the previous 20.

Nonetheless the decision to cut and run is being seen as a terrible blow to US credibility - to its reliability as a partner, and indeed to its moral standing in world affairs. How does this square with Mr Biden's clarion cry on taking office, that America was back?

Comparisons are being made with Vietnam - the similarities with helicopters shuttling US nationals away from a falling city being too much for the newspaper front-pages to resist. But in reality - despite the superficial similarities -there are some important differences, too.

South Vietnam collapsed some two years after US troops left. Indeed it looks as though the Americans expected their Afghan allies to soldier on for a significant period without them. The US was humbled by Vietnam - its population deeply divided and its military morale damaged. But while Vietnam turned out to be a tragic side-show in the Cold War, the US still ultimately won that contest. Nato was not weakened. US allies around the globe did not shy away from expecting US support. The US remained the pre-eminent superpower.

Afghanistan is altogether different. Internal divisions in the US over this conflict have in no way been comparable to Vietnam's. The Afghanistan mission was certainly unpopular at home but there were no mass rallies against it.

Joe Biden: 'I stand squarely behind my decision'

Crucially though, today's international context is dramatically different from that of the 1970s. The US - indeed the West in general - is engaged in multiple contests, in few of which they are outright winners. The Afghan collapse is potentially a disaster in the so-called war on terror. But in the wider conflict between democracy and authoritarianism, Washington's failure can only be seen as a serious set-back.

There will be smiles in Moscow and Beijing, at least for now. The Western model of liberal interventionism - promoted as a means of spreading democracy and the rule of law - has perhaps been tested to destruction in Afghanistan. One cannot see much enthusiasm for similar undertakings in the future.

Those of Washington's allies who joined in the Afghanistan project are smarting. They feel badly let down. Even British ministers, jealous of their oft touted "special relationship" with Washington, have been openly critical of President Biden's decision.

And for America's European allies in general, it underscores how dependent they are upon the US and how little their views count once the White House decides to go in one particular direction.

So bad news for the West. But how long-lasting will be the smiles in Beijing, Moscow and even Islamabad? It was Pakistan that nurtured and gave safe haven to the Taliban for its own geo-strategic purposes. But if renewed Taliban rule produces a simple turning back of the clock - if international terrorism finds a renewed haven - then Pakistan may find that the growing turbulence in the region has decidedly negative consequences.

China is happy to see the US failure. Indeed, if Mr Biden's reason to pull out from Afghanistan was due to his desire to re-focus US national power to rival a rising China, then this step has simply given China an opportunity to expand its own influence in Afghanistan and beyond.

China, though, must have concern, too. Its shares a short border with Afghanistan. It is actively persecuting its own Muslim minority and must be concerned at the possibility that anti-Beijing Islamist terrorists might seek to use Afghanistan as a base. No wonder then that Chinese diplomacy over recent weeks has been so eager to court the Taliban.

Russia, too, must have worries about the return of instability and terrorism. Maybe it feels a little better about itself now that the US has similarly been humbled by Afghan tribal fighters, just as the Soviet Union was in the late-1980s.

But its chief interest is the security of a large part of Central Asia, many of whose states are allies of Moscow. This summer Russia moved tanks to the Tajikistan-Afghan frontier for exercises intended to demonstrate its determination to prevent any spill-over from an Afghan collapse.

So in the short-term, the Afghan debacle certainly benefits the West's opponents. But their attitudes were not going to change anyway.

What really matters are the ramifications among Washington's allies. What will they take away from the Afghan experience? Beyond the immediate crisis, will the NATO countries, Israel, Taiwan, South Korea or Japan see the US as a less reliable partner? If they do, then Mr Biden's decision to quit Afghanistan will prove fateful, indeed.

- Published16 August 2021

- Published17 August 2021

- Published17 August 2021

- Published19 August 2021

- Published17 August 2021

- Published17 August 2021