Canada election: How vaccine mandates became an issue

- Published

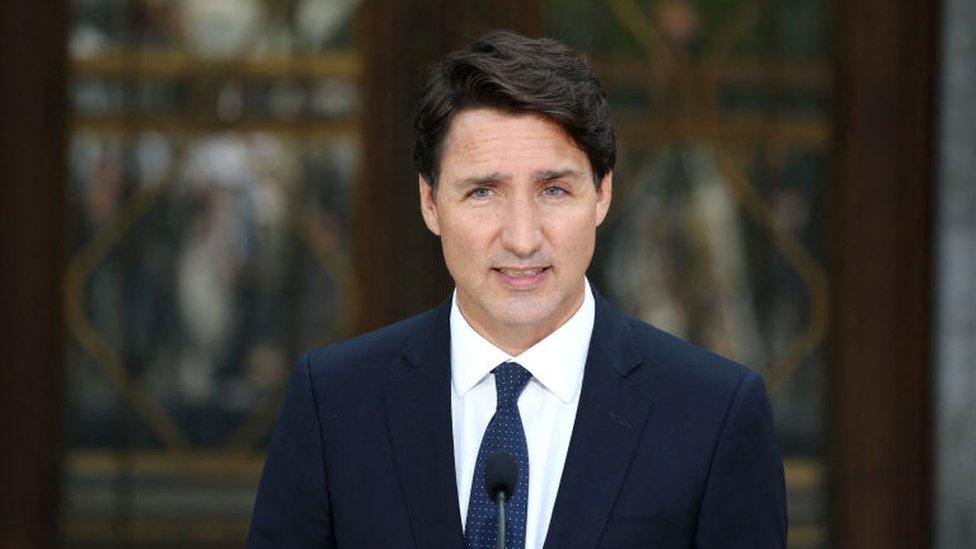

Vaccine mandates have emerged as an early wedge issue in Canada's snap federal election - called by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau two years before his current mandate expires.

Announcing the election on Sunday, Mr Trudeau said the autumn vote would allow Canadians to have their say on the country's pandemic recovery.

The Liberal leader has announced his government would mandate Covid-19 vaccination for bureaucrats, transportation workers and most air and rail travellers across Canada by the end of October.

Opposition leader Erin O'Toole - the most likely party leader to unseat Mr Trudeau - has come out against the mandate, saying he supports daily testing for such Canadians instead. He's also accused the prime minister of opting for a "divisive" vaccine strategy and playing politics with the pandemic.

Here's how vaccine mandates might shape the early days of the campaign.

What's the Liberal plan?

On Friday, just two days before the election was called, Mr Trudeau vowed to make vaccines mandatory for public servants, and Canadians travelling by air, train and ship.

His Liberal party has so far offered few details on enforcement.

On the campaign trail on Tuesday Mr Trudeau said there would be "consequences" for those who opt out of vaccination without a "legitimate medical reason", but did not elaborate further.

It's a slight change of tone for the prime minister, who in March said he thought vaccine mandates were "fraught with challenges".

"I think the indications that the vast majority of Canadians are looking to get vaccinated will get us to a good place without having to take more extreme measures that could have real divisive impacts on community and country", he previously said in an interview with Reuters.

It's also at odds with a since-deleted memo to deputy ministers posted to the government's website by Canada's chief human resources officer, which said the government would consider alternatives for those who refuse vaccination, such as testing and screening.

The civil service has said the memo was removed because it was "inaccurate" but the episode has spurred accusations of a cover-up by Mr O'Toole's Conservative Party.

Where does the opposition stand?

After dodging questions on vaccine mandates early on, Mr O'Toole formally came out against the vaccine requirements on Sunday evening.

Instead, the Conservative party would require unvaccinated government workers to take daily Covid-19 rapid tests and require rapid tests or proof of a recent negative test for air and train passengers.

Canadians "want a reasonable and balanced approach that protects their rights to make personal health decisions", he said.

Canada's opposition Conservative party leader Erin O'Toole campaigns in Quebec City

The broad strokes of Mr Trudeau's plan are supported by Canada's left-leaning New Democratic Party (NDP), led by Jagmeet Singh. On the campaign trail this week, Mr Singh called on the Liberal's to have their vaccine mandate in place by next month not October, and said disciplinary measures - including firing - should be used for those who fail to comply.

Both the NDP and the Liberals have required their candidates be vaccinated. The Conservative party has not followed suit.

A 'risk-free strategy'

Mr O'Toole has also criticised the Mr Trudeau for politicising Covid-19 vaccines, calling the move "dangerous and irresponsible".

In terms of politicising the pandemic, Canada's neighbour is a cautionary tale. The US vaccine programme has been hamstrung by partisan politics. Vaccinations are now a better predictor of US state election outcomes than almost any other demographic factor, external.

But while US politics and culture often migrates north, the proposed vaccine mandate seems unlikely to divide Canadians to the same extent, said Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant, a Canadian politics professor at Queen's University.

"I think it's a pretty risk-free strategy for the Liberals because there's strong support in Canada for vaccination, not only as evidenced by the number who voluntarily got them, but also opinion polls have shown again and again that vaccine hesitancy - much less vaccine opposition - is quite low," she said.

More than 80% of eligible Canadians (those aged 12 and older) have received at least one dose. A poll by Nanos Research for the Globe and Mail from earlier this month found an overwhelming majority of Canadians - 78% - would support or somewhat support a ban of unvaccinated people from gatherings in public places.

But vaccination rates vary across provinces, with Saskatchewan and Alberta are slightly lower than some neighbouring provinces, with first-shot rates of those eligible at a little over 75%. Both provinces are typically Conservative strongholds.

"Here's O'Toole's problem," Prof Goodyear-Grant said - that some of his base is out of step with most of the country.

Even so, the space between Mr O'Toole and Mr Trudeau is pretty thin.

"Everyone seems to be on board with maximising vaccine uptake," said Raywat Deonandan, a global health epidemiologist and professor at the University of Ottawa. "From a public health standpoint, it looks good to me."

Mr O'Toole has described vaccines as a "critical tool", calling them safe and effective. His plan does not make vaccines mandatory for civil servants and travellers, but it does require daily testing for those who opt-out - perhaps a strong incentive to get the jab.

From all of Canada's major party leaders, Dr Deonandan said, "the ultimate message is pro-vaccination".

- Published9 April 2021

- Published13 May 2021

- Published15 August 2021