Debt ceiling: What's next for the US debt limit

- Published

US lawmakers are running out the clock in a standoff over how much money the government can borrow

US lawmakers have temporarily put off a dangerous game of brinkmanship over lifting the debt ceiling - a limit on how much the US government can borrow.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen had warned Congress that the country would reach its ceiling by 18 October.

Republicans dared Democrats to resolve the conflict alone. Democrats called that move reckless. The showdown prompted fears of a default on the national debt.

But with the deadline only days away, Congress has voted to extend the debt limit through early December. On Thursday, President Joe Biden signed the bill into law, putting off the drama for a few weeks.

A default is still unlikely and has never happened in US history but if it did, it would have catastrophic implications for the US and the global economy.

Impasses over the debt ceiling are not new in Washington politics, but amid a sluggish economic recovery from the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, there were some jitters in financial markets.

Here's what you need to know about the debt ceiling debate.

What is the debt ceiling?

The US government spends more money than it collects in taxes, so it borrows to make up for the shortfall.

Borrowing is done via the US Treasury, through the issuing of bonds. US government bonds are seen as among the world's safest and most reliable investments.

In 1939, Congress established an aggregate limit or "ceiling" on how much debt the government can accumulate.

The ceiling has been lifted on more than 100 occasions to allow the government to borrow more. Congress often acts on it in a bipartisan manner and it is rarely the subject of a political standoff.

As the country has become more bitterly partisan, however, lawmakers have used the debt ceiling vote as leverage against other issues.

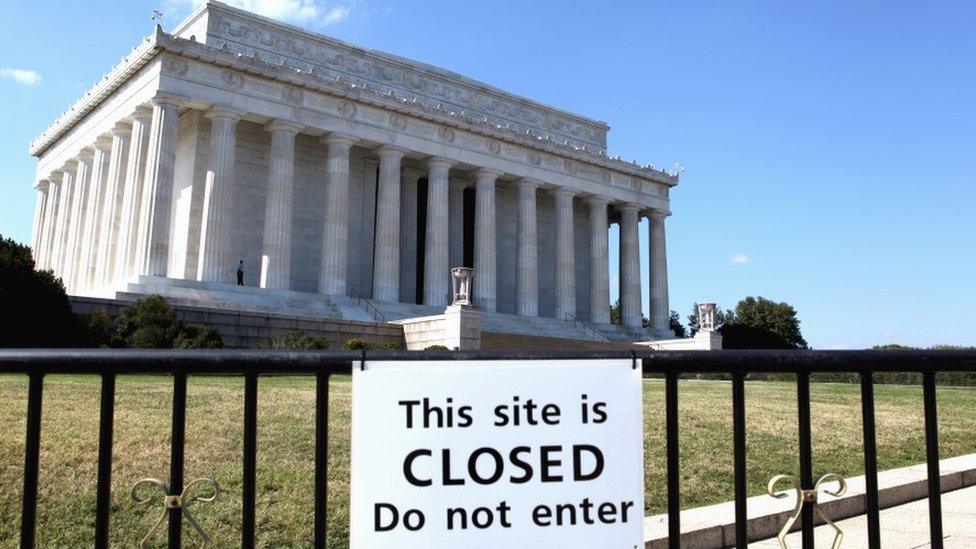

In a 2013 standoff, the last time the US was in serious danger of going over a "debt cliff", Republicans put up a blockade over the spending plans of President Barack Obama, a Democrat.

President Barack Obama negotiated intensely with Republicans to end a standoff over the debt ceiling in 2013

But, if history is any guide, lawmakers typically back down at the eleventh hour. This appears to have been the case again this month.

What would have happened without a raise?

For the first time ever, sometime in the second half of October, the US would have defaulted on its debts - which currently stand at around $28tn (£21tn).

Such an event would cause delays or bring service adjustments to every single government programme currently available, while also affecting federal funding for individual states.

A Goldman Sachs report has estimated the US Treasury would need to halt more than 40% of expected payments and financial aid to US households.

The Pentagon released a statement last week expressing concern that service members too may not be paid in full or on time.

Default may also trigger a spike in interest rates and ruin America's creditworthiness, making the US a more expensive place to live and damaging the economy. It would also bring turmoil to the stock market.

In a Wall Street Journal opinion piece last month, Secretary Yellen warned of "a historic financial crisis" that would leave the US "permanently weaker" if the debt ceiling was not raised.

Not raising - or temporarily suspending - the debt ceiling also threatens the health of the global economy, which would compound the impacts of the ongoing once-in-a-century public health crisis.

Investors around the world may sell off US assets and become less trusting of the US dollar, which has functioned as the world's reserve currency for decades.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has called for an end to Washington's "counterproductive brinkmanship" over the debt ceiling. It also suggested the cap should be replaced with an alternative financial mechanism.

What are Democrats saying?

Last week, Mr Biden condemned what he called "hypocritical, dangerous and disgraceful" Republican opposition.

Mr Biden said it amounts to "playing Russian Roulette with the economy".

There are 50 Democrats in the Senate, but in order to pass a measure on the debt ceiling without changing Senate rules, they require at least 10 Republican votes.

Democrats have pointed out that raising the debt ceiling is about paying off existing obligations rather than paying for new ones, and that Mr Biden's policies have only contributed to 3% of existing debts.

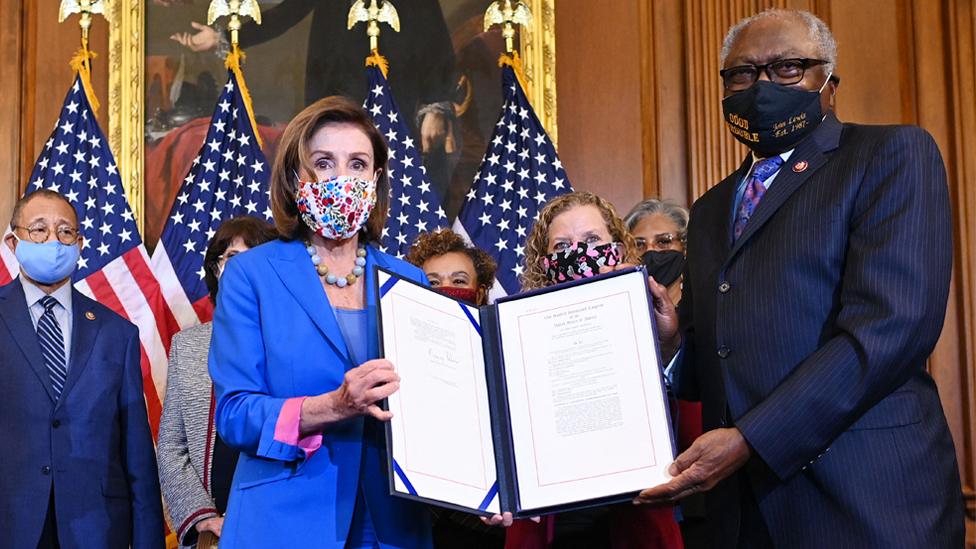

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, seen here with the top Democrats in Congress, has warned of a "historic financial crisis" if the US defaults on its debts

They also note that, during Mr Biden's predecessor Donald Trump's term, they joined with Republicans to raise the debt ceiling three times.

What are Republicans saying?

Senate Republicans have said raising the debt limit is the "sole responsibility" of Democrats because they hold power in the White House and both chambers of Congress.

They are frustrated by new spending proposals that Democrats are trying to push through without Republican support, through a procedural tool called "budget reconciliation".

Minority Leader Mitch McConnell tweeted last month that his party "will not facilitate another reckless, partisan taxing and spending spree".

Mr McConnell and other party leaders contend that if Democrats can use reconciliation to achieve their economic policy goals, they can also use it to take action on the debt ceiling.

Democrats have expressed concern over using reconciliation, saying it is too complex and time-consuming a route to take.

How might this get resolved?

After two attempts to bring up the debt ceiling measure through regular order in the Senate failed, Mr McConnell proposed an agreement last week that Democrats have now accepted.

As part of the offer, Republicans will come along with Democrats to raise the debt ceiling by a set amount - $480bn (£352bn) - to ensure bills are paid through 3 December.

Some Republicans, including former president Donald Trump, have grumbled that this amounts to "folding to the Democrats", but the temporary measure has now passed through both chambers of Congress.

Under the agreement, Congress will still need to vote again in December to avert a default.

The short-term fix gives the two parties more time to address their issues, which clearly remain unsolved.

Shortly after the Senate passed the bill, Mr McConnell wrote a letter to President Biden promising to "not provide such assistance again if your all-Democrat government drifts into another avoidable crisis".

Separately, lawmakers also kicked the can down the road last week when they passed a separate short-term bill to keep the government funded until December - so there may be a new round of headaches with the holidays right around the corner.

Related topics

- Published1 October 2021

- Published1 October 2023