US-Canada border: After 19 months, families to reunite

- Published

The world's longest land border has been closed for nearly 19 months.

The US-Canadian border has opened both ways to non-essential travel for the first time in 19 months. The closure has kept thousands of bi-national families split throughout the pandemic.

In March 2020, Jaslyn Declercq and her partner, Thomas Musgraves, began to plan their wedding.

The relationship had been a long-distance whirlwind after the pair met in an online chat room in 2017.

One year to the day on from their first conversation online - both Valentine's Day and Mr Musgraves' birthday - Ms Declercq drove four hours from her home in Tillsonburg, in southern Ontario, to Carey, Ohio to surprise Mr Musgraves and meet him in person for the first time. Two months and a handful of visits later, Ms Declercq became pregnant with their daughter, Maddie.

For almost two years, Ms Declerq made the drive to Ohio twice a month and the pair began to sketch out their plans for the future - marriage and Mr Musgraves' move to Canada.

Then, at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the US and Canada announced they would shut their shared land border to all non-essential travel. It threw an unwelcome block right in the middle of their 270 mile (434 km) commute but the couple wasn't overly concerned.

Watch: Emotional families reunite as US lifts travel ban

"We thought OK, it's going to suck, but it's only 30 days," said Ms Declerq, a 32-year-old mother of five. "We can do 30 days."

But that original month-long travel ban would be extended 18 more times, becoming the longest border restriction in both countries shared history. On Monday these restrictions will finally be lifted, allowing the reunion of thousands of families like Ms Declercq's.

From 8 November, the US allowed vaccinated travellers to cross the US-Canadian land border, following a similar move by Canada in August. A few days after the reopening, Ms Declerq and Maddie plan to drive down to Ohio to see Mr Musgraves.

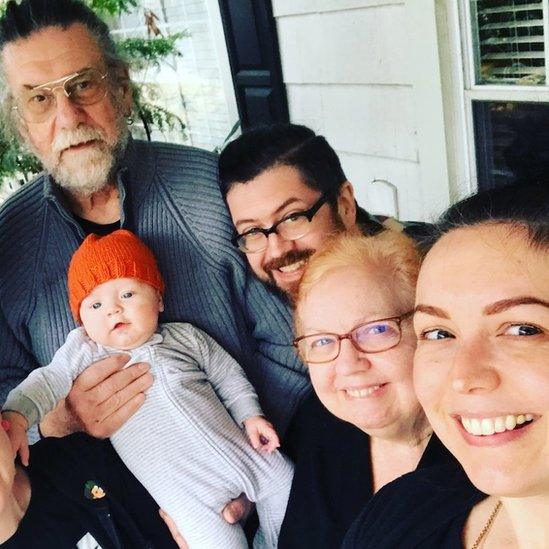

Thomas Musgraves and his daughter, Maddie, were separated for much of the pandemic

The travel ban had an asterisk. While both countries barred trips by land, the US continued to allow Canadians to fly in.

It was welcome news for those with means, including Canadian snowbirds hoping to fly south for the winter, but for thousands of families separated by the border, the exception was meaningless.

"We created an avenue for the well-to-do to cross the border, but for just day-to-day travellers, we made very few exceptions," said Christopher Sands, director of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute.

Especially for those in border towns - with few, if any, direct flights - a once straightforward drive became a convoluted and expensive journey.

"That's a very classist thing to say: 'You can just fly to see your family,'" said Devon Weber, founder of Let Us Reunite, an advocacy group for families separated by the border. "What was a 20 minute trip is now 12 hours and three airports."

For Ms Declercq and Mr Musgraves, it was almost unmanageable. Mr Musgraves took on a second job, working at a bowling alley in addition to night shifts at a manufacturing plant, to help save up for a round-trip flight from Canada.

"I saved up everything I had just so we would be able to spend Maddie's birthday, kind of, together," Ms Declercq said. She and Maddie flew in on Thanksgiving morning and stayed until 10pm on 6 December. Two hours later - officially Maddie's second birthday - she would no longer be eligible to fly for free.

All told, with flights, baggage and the obligatory Covid-19 tests, the trip cost $1,000 (C$1,246; £740). The drive there would have cost around $40 in gas.

Ms Weber's family will be all together this month for the first time in nearly two years

Ms Weber, an American citizen, lives with her husband, a Canadian, and their son in Montreal. The ban stopped her parents from visiting their only grandchild for nearly a year. And while she could drive in and out with her American passport, the roughly 10-hour drive with a toddler amid the challenges of the pandemic felt unfeasible.

"It was heartbreak," she said.

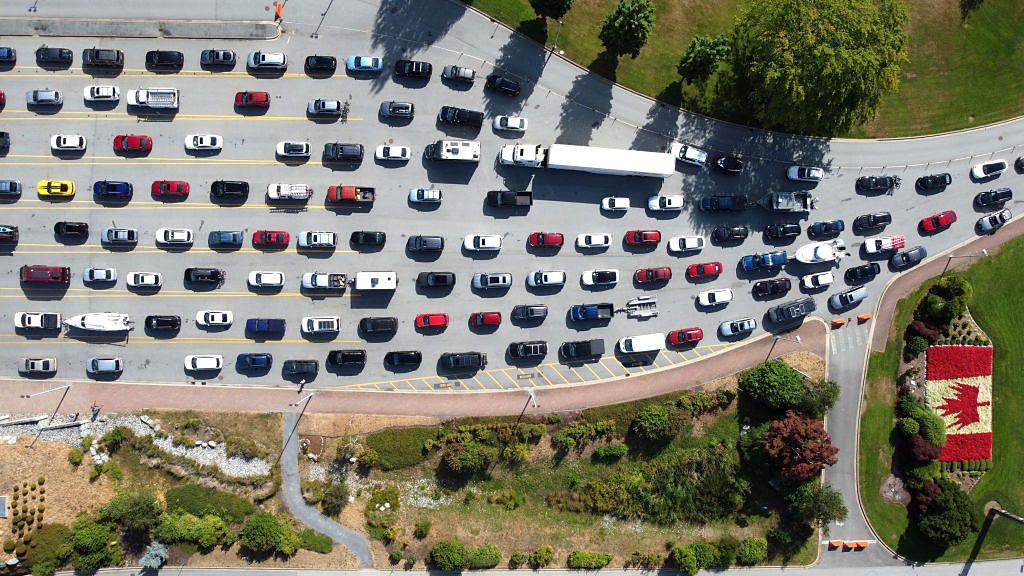

With the travel bans in place, non-commercial land border crossings to Canada dropped nearly 95% in the first six months of the pandemic, according to the Canada Border Services Agency.

In August 2020, Canada created an exemption for immediate family to visit loved ones, and Mr Musgraves was able to make the trip to Canada. He spent every one of his allotted vacation days - two weeks - in mandatory quarantine in Tillsonburg with Maddie, Ms Declercq and her four other children.

"It was amazing," Ms Declercq said. "Two solid weeks of quality time we hadn't had."

But between the visits, their relationship suffered. Mr Musgraves struggled with feeling that he wasn't really Maddie's dad, seeing her only over FaceTime and watching her grow closer to her uncle, grandfather, and the father of Ms Declercq's older children.

Exasperated by the lengthening separation and worn down by the uncertainty, they would fight, often late at night, and contemplate breaking up.

"There were a lot of times we would want to say 'we're done,'" Ms Declercq said. But in the morning they would decide to keep going.

In October of last year, Canada created a second exemption, this time for extended family - the grandchildren, grandparents, siblings, adult children and long-term partners of citizens or permanent residents. The United States did not reciprocate, for either family or extended family.

So on a whim, Devon Weber started a Facebook group to see if there were other families in her position. Overnight, 800 people had signed up to Let Us Reunite. The are now 3,000 families in the group.

For some, the closure of the land border turned a 30 minute drive into a hours-long journey

With Let Us Reunite, Ms Weber gathered stories and resources, lobbying lawmakers in both countries for family exemptions along the land border.

But little was done.

"This just wasn't prioritized within either administration," Ms Weber said.

Ms Declercq, also part of Let Us Reunite, reached out to her local member of parliament 76 times asking for help. She says she has yet to hear back.

On this issue, the coordination typical to the US-Canadian relationship "just wasn't there", said the Canada Institute's Mr Sands.

He added: "The human cost didn't exist anywhere in people's calculations."

To some, the economic cost was more obvious.

On a typical day, 400,000 people travel between the US and Canada, in addition to $2bn worth of goods and services. The vast majority of Canadians - somewhere around 85% - live within 100 miles of the US border.

For border towns like those dotted along southern Ontario and Quebec, northern Washington, New York and Vermont, where local economies depend on their neighbours' tourism, the cross-national bond is especially close.

There, the border shutdown was measured by absence. Canadians looking for deals were missing from upstate New York's shopping malls and restaurants. And for two summers, Americans were kept from their lakeside cabins perched on northern Ontario's lakes.

One particular US town, Point Roberts in Washington State, is only accessible by land with a trip through Canada.

"It's the longest undefended border, like everyone says," said Ms Weber.

"No one ever thought twice about crossing the border to go have dinner," she added. "With dating apps you set a radius of however many miles. The dating app doesn't know there's an international border."

Chelsea Perry and her husband of Calgary, Alberta meet with friend Alison Gallant of Bellingham, Washington from opposite sides of the USA-Canada border - once a regular occurrence

Still, for governments, the health risks of open borders loomed large.

"Frankly, it was always right to limit border crossing in general during the worst of the pandemic," said Raywat Deonandan, a global health epidemiologist and professor at the University of Ottawa. "I wish both sides had done that more rigorously."

But to Ms Declercq and Ms Weber, the insistence from both governments that the land border closure was in place solely for public health was inconsistent with flights coming and going each day and, eventually, the opening of bars, restaurants and sports arenas in both countries.

"I believe that Covid is a real disease, I believe in science, but no one was ever able to explain to us why it is safer to fly on a plane than it is to drive in your own private car," said Ms Weber.

For now, at least, that drive is possible. In two weeks, Ms Declerq and Maddie will drive to Ohio, just in time for US Thanksgiving and Maddie's third birthday.

Ms Weber, her husband and their son will also make a trip, driving to New York where Ms Weber's family will be all together for the first time in nearly two years.

"I was so exhausted from everything that it was almost hard to be excited. The fact that it took over 19 months for the US to do anything is extremely frustrating," she said.

"But I'm happy."

Additional reporting by Hannah Long-Higgins

Related topics

- Published13 August 2020

- Published10 August 2021

- Published13 October 2021