Kyle Rittenhouse case: Why it so divides the US

- Published

Two men argue outside court

Few US trials in recent years have generated such acrimony. What is it about the Kyle Rittenhouse case that so divides the country?

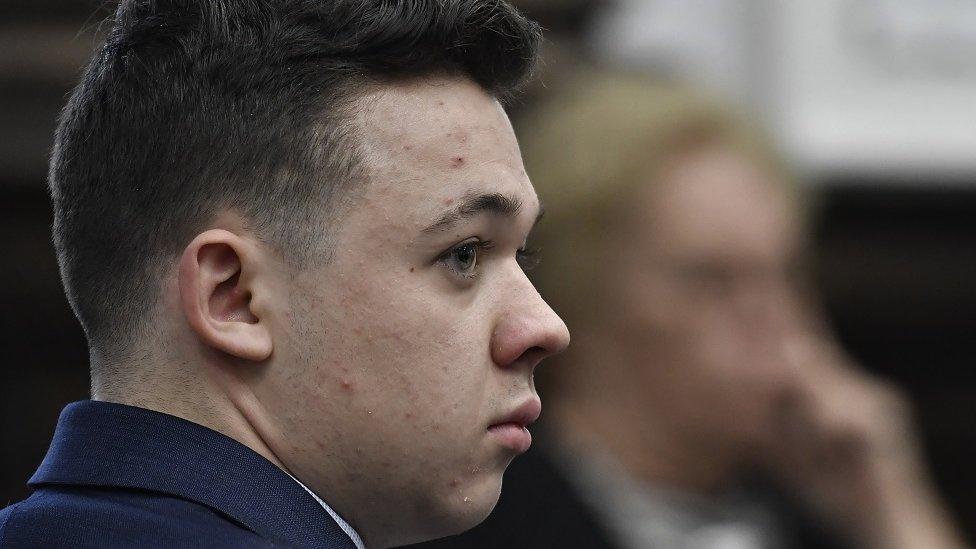

Inside the courtroom, the 18-year-old was visibly shaking as he heard the jury clear him of all five charges, including intentional homicide.

He killed two men during racial unrest in Wisconsin, but successfully convinced the jury he only used his semi-automatic weapon because he feared for his life.

Meanwhile, outside court cars drove past tooting their horns and cheering. Some leaned from windows to shout "Free Kyle!" and "We love the Second Amendment!"

Some were distraught at the verdict - one man collapsed on the courtroom steps in tears, saying if Mr Rittenhouse had been black and brandishing a weapon like that, he would have been shot dead.

Here's why the case provoked such deeply held emotions.

Self-defence

Kyle Rittenhouse's acquittal hinged on the specific details of Wisconsin's self-defence laws, taking into account Mr Rittenhouse's state of mind at the moment of shootings. The first occurred when Joseph Rosenbaum tried to grab Mr Rittenhouse's gun, the next two after two men - one of whom was armed - confronted Mr Rittenhouse following Rosenbaum's shooting.

The law considers whether Mr Rittenhouse believed himself to be in imminent threat of harm, but it does not factor in the choices he made in the hours and days beforehand that put him in the middle of a volatile situation, with guns drawn and tempers flaring.

Watch: The jury delivers the Rittenhouse verdict

The trial could prompt renewed consideration of self-defence laws across the US and whether they sufficiently weigh the totality of circumstances involving the use lethal force, particularly in a society where restrictions on the possession of firearms have been loosened.

The trend up until now has been to expand the right of self-defence in many states through "castle doctrine" and "stand your ground" laws that give individuals a presumptive right to use force to protect their homes and themselves, rather than to back down from a confrontation.

The divisiveness of the Rittenhouse trial could further fuel the debate over whether those laws go too far - or not far enough.

Race

Race is not central to this case, but for one man it is.

Jacob Blake, who is black, was shot seven times by a white police officer in Kenosha last year.

It was that shooting which sparked the violent protests in the first place. The police officer remains in the force. Mr Blake said in an interview that if Mr Rittenhouse had been of a different ethnicity, "he'd be gone".

Mr Rittenhouse was not immediately arrested after he shot three white men - two of them fatally - despite surrendering to police.

Black Lives Matter protesters outside the court say it is "white privilege" that has allowed the teenager to even have a fair trial.

Controversially, in closing arguments Mr Rittenhouse's defence attorney Mark Richards referenced the Blake shooting saying: "Other people in this community have shot people seven times and it's been found to be OK, and my client did it four times in three-quarters of a second to protect his life."

It's renewed this debate over exactly who is allowed to possess guns and then proclaim self-defence when they kill someone.

Guns

The Rittenhouse trial has once again highlighted laws restricting gun possession and use in America that varies widely by state and local jurisdiction. Often the regulations are less than precise, the product of intense legislative debate over the types of firearms covered and under what circumstances the laws apply.

A day before closing arguments in the Rittenhouse trial, Judge Bruce Schroeder ordered that one of the charges - that Mr Rittenhouse violated a state law prohibiting a person under 18 from possessing a "dangerous weapon" - be dropped because the rifle Mr Rittenhouse was carrying wasn't prohibited to him.

The decision turned on the length of the firearm's barrel, which would have been prohibited if it were a few inches shorter.

Gun-control activists have cited this as yet another example of the kind of loophole that could be remedied by more uniform national gun laws.

While the 30-year-old Wisconsin law contains a provision to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to go hunting, they view the weapon Mr Rittenhouse was carrying as clearly "dangerous" in the circumstances he used it.

Gun rights activists, on the other hand, have celebrated Mr Rittenhouse's right to possess such weapons and use them to defend himself.

"If it wasn't for 17-year-olds with guns," tweeted Ohio Republican Senate candidate Josh Mandel, "we'd still be British subjects."

The judge

Bruce Schroeder is the longest-serving circuit judge in the Wisconsin state court system. He was appointed by a Democratic governor in 1983 and has won election to his seat seven times since then, each by overwhelming margins.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the judge would become a focus in such a high-profile, nationally televised trial, but the unusual American tradition of electing judges has made a delicate political situation even more fraught.

Over the years, Judge Schroeder has developed idiosyncrasies, such as allowing defendants to conduct the random drawings that select their final jury and quizzing jurors on esoteric trivia. He's also established a reputation as a pro-defence jurist - one further cemented by his testy exchanges with prosecutors during the Rittenhouse trial.

Bruce Schroeder

Given the highly charged political nature of the trial, many of those quirks and choices have been scrutinised for evidence of bias. His rulings to drop the illegal firearm charge and saying the men Mr Rittenhouse shot could not be called "victims" were criticised by many on the left.

Even his choice of mobile phone ringtone, the patriotic anthem God Bless the USA - a staple of Donald Trump rallies in recent years - made headlines as possible evidence of his political proclivities.

Legal analysts have generally concluded that Judge Schroeder's rulings have been within the norms for such proceedings, but with the impartiality of the entire US criminal system challenged in last year's protests against institutional racism and police shootings - including the one in Kenosha - those norms are under scrutiny, as well.

Vigilantism

The facts of that night have never been up for debate - Kyle Rittenhouse killed two men and injured a third.

Instead the jury had to work out why he did it. He was being chased by a group of people when he fired the fatal shots. Was he acting in self-defence or was he a dangerous vigilante provoking an already volatile situation in a city he did not belong to?

Many groups who want tighter gun control say it was the latter. They are worried that by being cleared of the charges, Mr Rittenhouse's case now sets a precedent - that anyone can turn up to angry protests with a gun, but without facing any consequences.