Long December looms for US Democrats

- Published

It's going to be a long December for Democrats, and there's reason to believe next year may not be any better than the last.

That's the feeling in the party that, for the past 10 months has controlled the presidency and both chambers of Congress but finds it's moving against strong political headwinds at this point.

While significant achievements have been realised - a massive Covid relief bill and a historic level of infrastructure funding - the US public seems more concerned about the state of the economy and the continuing disruptions from a Covid-19 pandemic that could see another winter spike in infections and deaths.

Some of that is beyond the control of Biden and the Democrats.

What is squarely on their agenda for the month, however, is a series of legislative obligations and aspirations that could determine the success or failure of the first year of the Biden presidency.

It could also be all Biden gets during his entire first term in office, given that politicians will be busy campaigning for re-election next year and the prospect that Republicans could take back control of at least the House of Representatives at the start of 2023.

Democrats in Congress successfully passed a resolution that avoided a government shutdown last week, but that's just the start of their work.

Here's a look at what's left to do.

Better 'Build Back Better' Soon

To paraphrase Richard Nixon, this is the big enchilada for Joe Biden and the Democrats.

It's the nearly two-trillion-dollar spending package that increases funding for government health-insurance programmes, expands tax credits for low-income families, provides government-funded universal preschool, creates a family and medical leave programme and invests roughly $500bn in addressing climate change.

This would be (mostly) paid for by increases in taxes on corporations and wealth earners, as well as through stepped-up revenue-collection enforcement.

The bill passed the House of Representatives in October but it is stuck in the Senate, as Democrats wrangle over the exact scope and cost of the legislation.

Because the Democratic majority in the Senate rests on Vice-President Kamala Harris' tie-breaking vote, the party only has a limited number of opportunities for a straight up-or-down vote and, consequently, has had to combine all these different parts of Biden's legislative agenda into one big package.

That's created a cumbersome process that has dragged on for months now - and leaves some Democratic priorities, like immigration reform and voting rights, out in the cold.

Meanwhile, anything that might make it in the bill is subject to the whims, desires and delays of every Democratic senator.

Negotiations, as they say, are ongoing. But the longer the process takes, the longer Democrats have to wait to reap any political benefits from the legislation and the greater the chance some new obstacle appears that tanks the whole thing.

Debt ceiling blues

The thing about kicking a can down the road is you eventually catch up to it. Then you're right back where you started. Such is the situation with the debt ceiling, the legal requirement that Congress authorise any increase in the overall US national debt, a number that has been growing by leaps and bounds of late.

Back in October, Democrats and some Republicans voted for a limited increase in the debt limit to avoid what would have been a first-ever, economically cataclysmic default on the US national debt. Republicans did so grudgingly, however, with Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell arguing that since Democrats run Congress, they should vote to extend the limit on their own.

Shortly thereafter, Democratic Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer gave a speech blaming Republicans for politicising a solemn national obligation to pays its bills. That prompted McConnell to lash out, promising that when the next debt limit approached in December, his party wouldn't offer any help at all.

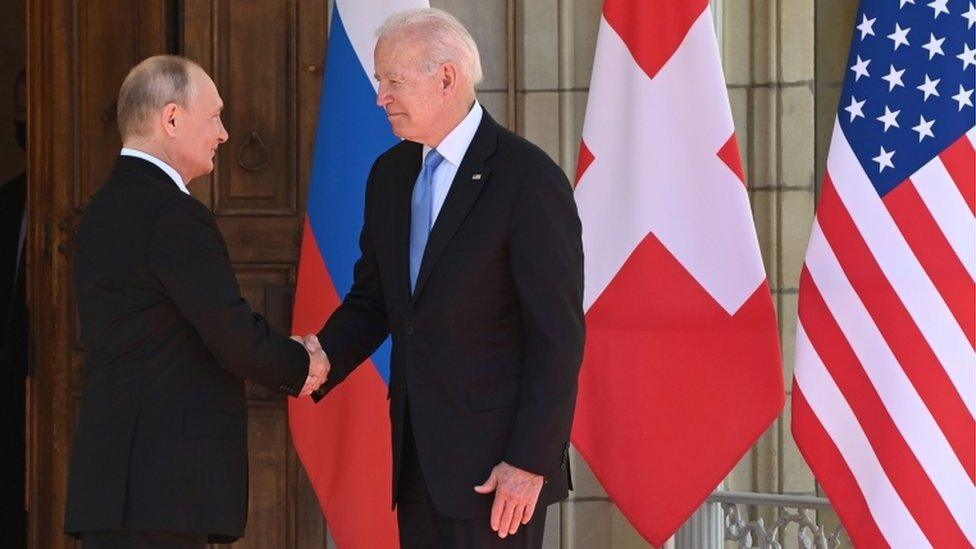

Democrats, in happier times, sign the bipartisan infrastructure package

That brings us to the current standoff, with the new debt limit set to be reached on 15 December unless Congress acts.

Democrats have several options at this point to resolve the crisis.

They could do as Republicans demand, holding their bare congressional majorities together to approve an increase without Republican help.

That would require some elaborate parliamentary manoeuvres in the Senate, however, delaying work on the party's other legislative priorities (see below). It also, Democrats fear, sets up their party's officeholders for attack by Republicans as profligate spenders when the congressional mid-term elections roll around next November.

The other option is to force a showdown in the hopes that Republicans, facing the prospect of a US debt default, blink once again.

The thing about games of chicken, however, is that if no-one swerves you could end up with a head-on collision.

Guns and bombs away

This should have been the easy part.

Defence authorisation is one of the few spending bills Congress reliably passes, having done so every year for the past six decades. Few politicians, even during the highest moments of partisan acrimony, want to risk being accused of being soft on the military or unenthusiastic in their support for US soldiers and sailors.

The House of Representatives approved its version of the National Defence Authorisation Act by a comfortable bipartisan majority back in September. That teed up the Senate to follow suit - and everything has been downhill since then.

A handful of Republicans (and a few Democrats) are pushing for votes on a variety of changes to the legislation, including (deep breath) spending cuts, sanctions relating to a Russia-to-Germany energy pipeline, new language supporting Taiwan, a condemnation of Uyghur forced labour in China, modifications to US Afghanistan policy, weapons aid to Ukraine, inclusion of women in the (currently inactive) military draft and the termination of the 20-year authorisation of military force for the post-9/11 "war on terror".

The Senate got a late start on considering the legislation to begin with, and as the clock ticks towards the new year, the rush of demands and alterations is proving daunting.

There's even a proposal to tie the debt-limit extension to the defence authorisation in the hopes of killing two birds with one stone (but, more likely, just wasting stones).

For success in the Senate, Democrats will have to get everyone on board, including the moderate Joe Manchin

Senate leaders have tried to trim the thousand-plus proposals down to a select few, but those efforts have been unsuccessful so far.

Anything the Senate does eventually pass will have to go back to the House of Representatives for another vote, meaning that even if the chamber gets its ducks in a row the legislative struggle could come down to the year's final days.

An eye on China

It may seem like the Senate is the major source of legislative headaches for Democrats - and given the chamber's robust protection of minority-party prerogatives, that is mostly the case.

There's one other piece of legislation - a $250bn grab-bag of proposals to invest in technology research, enact new trade restrictions and prioritise US-made products for infrastructure spending - that has been approved by the Senate and is currently languishing in the House of Representatives, however.

The bill, called the US Innovation and Competitiveness Act, is meant to level the business and investment playing field with China. It's the brainchild of Senate leader Schumer, which might explain why it cleared his chamber with (relative) ease back in June.

Some liberals in the House view it as a sop to big corporations, however. Some businesses fear the legislation will damage US-China trade relations. The Chinese government, for its part, has vehemently opposed the bill.

Given that congressional Democrats have bigger fish to fry at the moment, prospects for a resolution anytime soon seem dim.

Related topics

- Published5 December 2021

- Published19 November 2021

- Published3 December 2021