Why are certain school books being banned in US?

- Published

A growing number of US parents are alleging that school books are obscene or otherwise harmful to children. It's creating an increasingly divisive political battle that could spill over into upcoming national elections.

Yael Levin-Sheldon, a mother of two who lives near Richmond, Virginia, recently heard about a book that a teacher in an area school brought into the classroom. She made a note of the title, The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person.

The title alone, Levin says, is racist - and it's not the kind of book that should be available to children in public schools.

"Now think of it saying, 'on being a better black person'," she said. "Would that be ok?

Levin-Sheldon is the Virginia chapter president of the conservative parents-rights group No Left Turn in Education. Her organisation compiles a list of books it says are "used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students" and "divide us as a people for the purpose of indoctrinating kids to a dangerous ideology".

The list includes Margaret Atwood's dystopian novel The Handmaid's Tale and White Fragility by Robin Diangelo. The Black Friend, a New York Times best-selling memoir by Frederick Joseph recounting his challenges as a black student in a predominantly white high school, isn't on the list. At least, not yet.

Books such as Joseph's - offering critical views on topics like US history or race - gained new prominence in school curricula and library collections as a response to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 and educational efforts to address concerns about persistent racism in the US. No Left Turn contends that the works should be taught in context, along with other texts that provide a different (and assumedly more positive) view of America's past. And parents, Levin-Sheldon adds, should have the choice of opting out of those lessons.

Other works, however, particularly ones that touch on human sexuality in explicit detail, should be outright prohibited, the group argues.

"When it comes to pornography and paedophilia," Levin-Sheldon says, "that's when we want those books removed."

This, she adds, is all her group is seeking. It's not too different from what free-speech advocates and educators say they would like, as well - a conversation between parents, teachers and school librarians, balancing moral and educational interests and conducted with the best interests of the children in mind.

In practice, however, it hasn't always worked out that way.

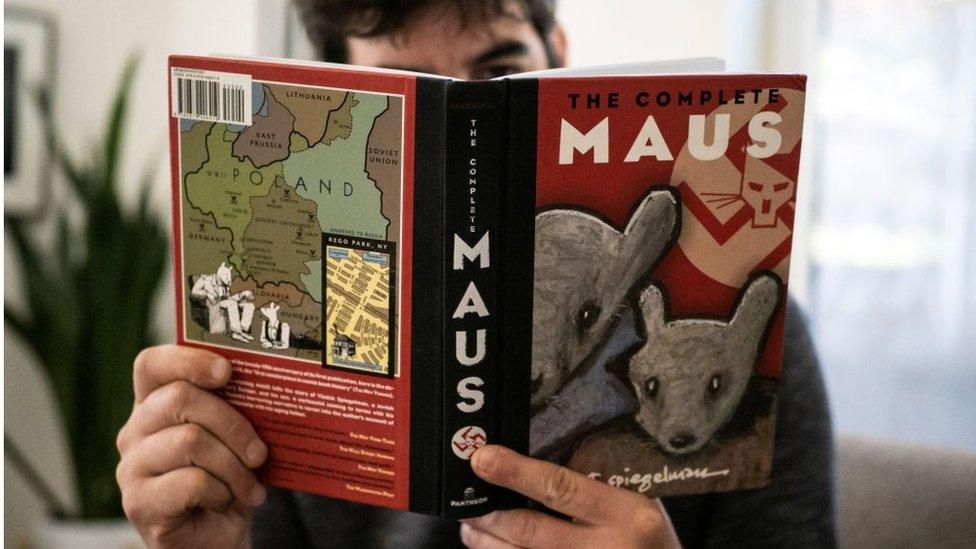

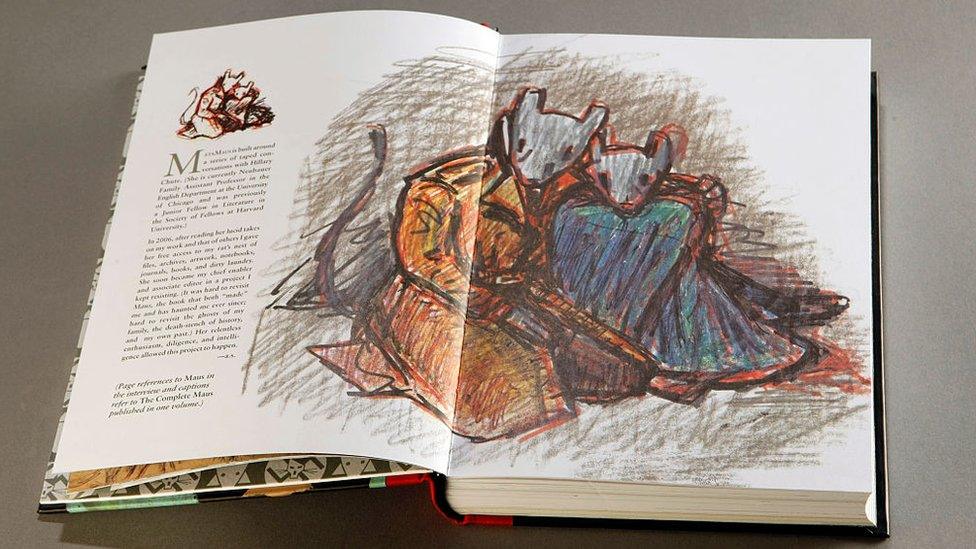

Maus, which depicts the suffering of Jews during the Holocaust, was banned in Tennessee

A rising tide of complaints

A state legislator in Texas produced a list of more than 850 books that he contended may cause students to feel "discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress" because of their race or sex. A Dallas Morning News review found 97 of the first 100 books on the list were written by ethnic minorities, women or LGBTQ authors.

A school district in San Antonio pulled 400 of those books from its libraries without any formal review process or specific complaints from parents.

A Tennessee school board removed Maus, a Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, from its eighth-grade curriculum because of profanity and anthropomorphised mouse nudity.

In Polk County, Florida, a school removed 16 books pending review, including award-winning novels The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini and Beloved by Toni Morrison, because they contained "obscene material".

Challenges have come from the left, as well. A school district near Seattle, Washington, dropped the 1960 Harper Lee classic To Kill a Mockingbird from its curriculum because of its depiction of race relations and use of racist language.

Characters' use of racist epithets also prompted efforts last year to limit the teaching of John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men in school districts in Mendota Heights, Minnesota, and Burbank, California.

The American Library Association keeps track of the number of complaints lodged against books in school libraries and has recorded a marked increase over the past year. According to preliminary data, from September through November of 2021 the association tallied 330 incidents. The total number reported for all of 2019, the last year schools across the US were in-person for the entire year, was 377 - suggesting that the final 2021 numbers ultimately will dwarf previous amounts.

The cumulative effect, says Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the association's Office for Intellectual Freedom, is significant damage to open discourse and learning across the country.

"We are a government, a society that purports to protect freedom of speech, the freedom to access information to make up our own minds, to engage in a broadly liberal education," she says. "And we're now finding that we have a movement to shut down that conversation, to deny those rights, particularly to young people."

'Covid lemonade'

According to Tiffany Justice, co-founder of the parents group Moms for Liberty, the surge in parental interest can be attributed, at least in part, to the remote learning policies schools implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic. For the first time, they say, many parents had an up-close view of what their children were being taught - and they didn't like it. She calls it "Covid lemonade," because the pandemic had a silver lining.

"We had never really been able to get parents as invigorated as they have been seeing the curriculum up close and personal while they were sitting with their child doing the work," she says. "We saw it as an opportunity to really engage parents even more and to get them involved in their children's education."

Social media has also proved to have a potent effect on the scope of the movement. Activists says it has helped their groups organise across the US, as parents learn that they are not alone in their concern. On the other side, groups like the American Library Association have found the same books identified in complaints turn up again and again, as lists - like the one on the No Left Turn websites - are circulated online.

"Social media is amplifying and driving both the messages of these groups that are pursuing a particular agenda, as well as individual challenges that crop up in a community," Caldwell-Stone says.

At the heart of the issue is a debate over the role of parents, schools and the rights of students in the classroom. Both Levin-Sheldon and Justice point out that until children turn 18 they are minors, and parents should be able to review the ideas and subject matters to which their children are exposed - even if that's not supervision all parents want to exercise at home or in the classroom.

Free-speech proponents counter that libraries are meant to serve an entire community of students, not just the ones with the most prudish parents. And although students are not adults, they still have rights - and agency. A dialogue between parents, teachers and librarians is important, but if teenagers seek out information on a topic of interest, they should have access to it.

"There's this notion that young people are in search of the most illicit material in every area of their lives, all the time," says Jonathan Friedman, director of Free Expression and Education at PEN America, an author's free-speech group. "I don't think that's true. I think people go to a library there's usually an alignment between reader and text."

The politics of anger

As the push to pass judgement on - and remove - certain books from schools has become a national drive with national attention from conservative and liberal media, tempers have become increasingly frayed.

A school board meeting in Flagler County, Florida, to discuss the removal of the book All Boys Aren't Blue devolved into obscenity-laced protests and counter-protests. (The board's decision to approve the book's use was ultimately overruled by a county official).

Meetings in other parts of the US have had to be cancelled or delayed because of threats against public officials. During a school board meeting in Carmel, Indiana, last July, where parents were taking turns reading out explicit passages from books that they believed should be removed from their school library, a man was arrested after a handgun fell out of his pocket.

Levin is quick to note that her group does not approve of such parental conduct and they seek to train their members to behave "respectfully and professional" at school board meetings. Justice agrees, calling her members "joyful warriors", but adds that parents have reason to be angry.

"Yeah, they're upset," she says. "Their kids aren't learning in school. They're sending their kids to school and their kids are learning more about - who knows? Not reading and writing."

A protest against critical race theory at a school in Virginia

Anger can be a potent force in politics, and conservative politicians - and Republican-dominated legislatures - have sought to harness the passion.

Last November, Republican Glenn Youngkin won the Virginia governorship by campaigning on education and parental rights. One of his television adverts featured a mother who objected to Morrison's Beloved being taught in her son's high-school English class.

As November's mid-term elections approach, with control of the US Congress and many state governments at stake, more candidates on the right are following suit.

Matt Krause, the Texas legislator with the 850-book list, is running for state attorney general. On Tuesday, the Indiana state Senate approved a bill that would allow the criminal prosecution of school librarians for disseminating "material harmful to minors". The Oklahoma legislature is considering a bill that would ban public school libraries from offering any books on sexuality or gender identity.

One thing Americans find hard to talk about

Friedman warns that efforts to remove books will have an adverse impact on librarians and school officials, who could engage in "soft censorship" by pre-emptively pulling titles they worry could spark controversy. It could also have a chilling effect on authors and publishers, who might shy away from controversial topics and stifle their creativity.

"If you are telling a story that's on the borderline of any of these issues right now, you're going to think twice about writing in a way that might get banned or draw national attention," he says. "You're not going to publish that book; you're not going to give that talk publicly about it."

Ashley Hope Perez is one of those authors feeling the pressure. In a recent issue of Texas Monthly, she describes how she was harassed after her book Out of Darkness was criticised as being obscene in meeting of a school board near Austin.

"Ugly phone messages calling me a 'degenerate piece of -', emails that were little more than expletives strung together, social media comments saying I was 'literally SATAN' and suggestions that I hang myself," she writes. "The attacks on Out of Darkness say far more about our cultural moment than they do about my book."

She notes that her book was first published six years ago with little controversy. The political ground, it seems, has shifted significantly since then.

More by Anthony

- Published31 January 2022

- Published1 February 2022