New Republican splits over Trump and riot

- Published

US political observers were recently treated to a split-screen spectacle of Republican Party fratricide.

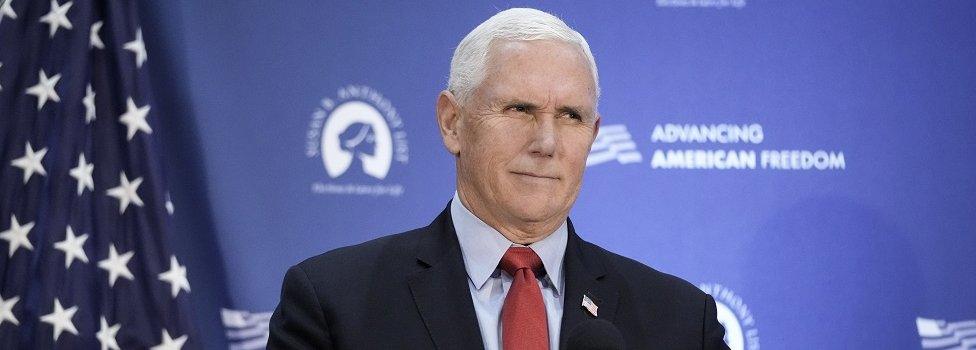

In Florida, former Vice-President Mike Pence was criticising his former boss by name for the first time since joining the Republican presidential ticket in 2016. And in Utah, the Republican National Committee was censuring two of its own for working with Democrats to investigate Donald Trump and the 6 January Capitol attack.

The day's events highlight the unpredictable political cross-currents as Republicans gear up for what they hope will be successful November congressional and state elections and a bid to unseat President Joe Biden in 2024.

Politicians, and prospective candidates, are making calculations on how to succeed in an environment where Mr Trump is out of office but not out of power.

Here's a look at how some of the major players are navigating the waters.

Mitch McConnell

On Tuesday, the Senate minority leader made headlines by saying that the 6 January attack on the US Capitol was a "violent insurrection for the purpose of trying to prevent the peaceful transfer of power".

He also took issue with the move by the Republican National Committee to censure Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger, the two Republican members of the House of Representatives who are serving on the committee investigating the violence at the Capitol.

That McConnell holds these views isn't exactly breaking news. He was sharp in his criticism of Mr Trump's actions - and responsibility - in the weeks after the Capitol attack. Behind closed doors, according to the Washington Post, McConnell was even more candid, saying that his party was spending too much time highlighting "the only liability we have".

McConnell, as savvy a political insider as there is, views the Capitol attack - and the talk of fraudulent elections that incited the violence - as his party's political Achilles' heel in what would otherwise be positive political climate for Republicans with the November mid-term congressional elections approaching.

McConnell isn't on the ballot in November, so Mr Trump's attacks on him - and they came quickly after his recent remarks - will do little harm. But his only hopes of winning his old job as Senate majority leader back next year is if Republicans net a Senate seat in November - and his calculation is that Trump, and his supporters, are making that job harder.

Kevin McCarthy

In his heart of hearts, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy may feel the same as Mr McConnell regarding Mr Trump and his impact on Republican mid-term electoral success. The Californian, after all, offered his share of criticism of the then-president in the days after the Capitol attack.

Since then, however, Mr McCarthy has assiduously courted the former president and tried to avoid getting drawn into the public debate over Ms Cheney and Mr Kinzinger's fate in the party. That's because while Mr McConnell seems confident in his hold on the leadership position among Senate Republicans (a more moderate and institution-minded group), the Republicans in the House of Representatives are an aggressively pro-Trump crowd. If his party takes back control of the House in November, McCarthy will need near-unanimous support from Republicans to be elected speaker of the House.

Already, there are some more extreme members of his party, such as Georgia Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor-Greene, who have expressed doubts about Mr McCarthy. If her doubts, and those of others who share her views (a number that is likely to grow after November's elections), grow McCarthy could find himself in the majority in the House but blocked from the top job.

Ron DeSantis

For an accurate guide of which way the political winds are blowing in the Republican Party, the best place to look is not Congress but among the aspirants to the party's presidential nomination in 2024. To win the White House, a Republican will have to win primary contests across the nation, and not just prevail in one state or congressional district.

At the moment, an early contender for the prize (should Trump himself not run) is Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. And while he and Trump have jostled a bit of late, there's no question that the Florida governor views any potential path to higher office as dependent on the good graces of the former president and, more importantly, his cadre of devoted supporters.

When asked recently about Ms Cheney's censoring, he said that she had gone "off the rails" and is out of step with her party. He maintained that Mr Trump is a friend and that talk of a rift between the two is "total bunk".

Mr DeSantis, you might recall, was the candidate who first campaigned for governor with a television advert that featured one child in a "Make America Great Again" onesie and another "building a wall" out of play blocks. The Florida governor, and many other who seek office, are going to hold tight to Trump as long as they can.

Chris Christie

If Mr DeSantis is pursuing a frontrunner's course for the White House, currying favour with Mr Trump and his supporters, there are a few potential candidate who may be eyeing a less crowded, long-shot path that involves resistance, not supplication.

A politician like former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who ran unsuccessfully for president in 2016 and subsequently endorsed Mr Trump, has been relatively outspoken in his criticism of the former president over the past year.

He's called the 6 January attack a riot that was aimed at pressuring Vice-President Mike Pence and congressional Republicans to overturn the election results. And he's said Mr Trump "didn't get a lot of stuff done" while he was president - an incomplete border wall, no infrastructure law and no repeal of Democratic healthcare reforms.

"The management style is the problem," he said of Mr Trump back in November.

At the moment, alienating Mr Trump's base - and possibly drawing the ex-president's ire - doesn't seem like a winning play. If the ground shifts, however, and Mr Trump is viewed in a less favourable light among Republican voters by 2023, risk-takers like Mr Christie could find themselves at the head of the pack, instead of in the rear.

Mike Pence

Speaking of Mr Pence, he finds himself in an unusual - and unusually uncomfortable - position for a former vice-president. Under normal circumstances, someone with his credentials would find himself with a leg-up in future electoral contests. While ex-veeps seeking the presidency don't always win the job, they frequently get their party's nomination - Al Gore, George HW Bush and Walter Mondale being a few recent examples.

The nature of the number-two job is that, while it comes with little in the way of public glory it does allow the occupant to build the kind of grass-roots party support needed to win primary contests.

The grass-roots base of the Republican Party - the Trumpist portion of it, at least - views Mr Pence as a traitor, however, because he didn't accede to Mr Trump's demand that he reject congressional certification of Mr Biden's presidential victory.

So if Mr Pence can't campaign for president - a job he clearly wants - as a front-runner, he'll have to do it as an insurgent. Like Mr Christie, he can try to wear his willingness to stand up to Mr Trump as a badge of honour.

"President Trump is wrong," Mr Pence said last Friday, calling the idea of his being able to overturn the election as "un-American".

At least so far, Mr Trump has held off making a full-on attack on his former number-two. But former White House adviser Steve Bannon has offered a flavour of what's in store, labelling Mr Pence a "stone-cold coward" who would carry his failure to support Mr Trump to his grave.

Mr Pence doesn't have a great hand, but it's the only one he can play.

Ronna McDaniel

While Mr Pence was busy name-checking Mr Trump at a conference in Florida, the Republican National Committee was passing a resolution condemning two of Mr Trump's sharpest critics in Congress, Ms Cheney and Mr Kinzinger.

The resolution didn't just accuse the two of hurting the Republican Party, it went on to say that their congressional investigation into the 6 January attack was persecuting ordinary citizens engaged in "legitimate political discourse".

That line left the Republican committee's chair, Ronna McDaniel, scrambling to do damage control. She fired off a press release saying the party wasn't referring to the attack on the Capitol itself and blaming the media outlets that reported it as such for being biased.

The resolution, however was passed by near-unanimous voice vote, with no discussion of its contents in general or the "political discourse" line in particular. Within the Republican Party rank and file, the language attacking the committee, its investigation and its Republican members is common.

There have been reports that Ms McDaniel - the niece of Senator Mitt Romney, a prominent Republican Trump critic - considered herself to be in an "impossible spot", torn between the party elders in Washington and the grass-roots activists who backed the resolution. After it passed, Mr Trump called Ms McDaniel personally to thank her for her support.

All this reflects how rapid and complete the shift within the Republican Party apparatus has been. Back in 2016, when Mr Trump first ran for office, it was the party infrastructure that resisted his ascent, right up until his formal nomination at the national convention in Cleveland.

Now, it is the rank-and-file membership of the party, the grass-roots activists who serve as national committee members and state and local party officials, who are some of the fiercest Trump loyalists.

This is a reality that Ms McDaniel, by her actions, tacitly acknowledged. Republicans who consider a break with Donald Trump will have to understand that they are not just fighting the former president, but the party itself.

Related topics

- Published31 January 2022

- Published1 February 2022