War in Ukraine: The danger of wishful Western thinking

- Published

A man walks away from a building hit by Russian fire in Kharkiv on 25 March

In the second episode of Volodymyr Zelensky's very funny comedy series, The Servant of the People, one of the spooky bad guys says of Zelensky's character, the newly elected President of Ukraine: "He's known for being iron clad and brave."

That was the point I reached for the remote, pressed pause, and took a deep breath.

The 2015 series has just starting airing here in America, and for those of us who are new to it, it's a bit surreal. Every time you catch yourself chuckling, you then start to feel sad. It's emotionally draining. I find I can't watch more than an episode at a time and I do so with a certain dread. Friends have told me they can't watch it at all.

And it's not because it's bad. It's a good show and Zelensky is a talented actor. He's charming and self-deprecating. No, it's hard to watch, because we fear what's going to happen to the real President of Ukraine.

There's another scene in that same episode where the new president, Vasyl Petrovych Holoborodko, is introduced to his security detail body double. A smarmy political flunky turns from the double to Zelensky and says, "He'll die from a sniper bullet for you," then he laughs out loud at Zelensky's look of horror. "But," the flunky chortles, "I think it won't come to that."

And then your stomach turns, because right now it feels like the whole Western world is watching Ukraine and just praying that it won't indeed come to that.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visiting wounded Ukrainian troops on 13 March

No-one would wish any of this suffering on Ukraine. But for the moment Zelensky and the brave people he leads are heroes in a world that has been short of them.

We've come out of a dark period of ugly political division and tragic medical crisis and we are longing for something good to believe in. Forty four million brave Ukrainians seem to have risen to the challenge and given us cause for hope in the power of the underdog.

We root for them. We are amazed by their resilience. We long for them to survive and stay free. So it's understandable that we may fall victim to what one analyst eloquently described as Western wishful thinking.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

APPROACH TO KYIV: Battle on capital's outskirts

MOSCOW SHIFT: Change of emphasis or admission of failure?

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

After the invasion one US senator told me confidently that whatever happened, the Ukrainian people would be free. It was the optimism I've come to expect, and appreciate, from US politicians. And we hope it will be true.

History reminds us, however, that good doesn't always prevail. Not against Russia anyway.

Ask the Syrians, still stuck under the boot of the Assad regime, their cities destroyed by Russian bombs. Ask the Chechens, who saw their capital flattened on the orders of Vladimir Putin. Or, ask the countless brave Arabs, Iranians, Belarusians and Myanmarese who risked their lives to protest against oppressive rulers, with little to show for it.

In the suburbs of Ukraine that have become Putin's latest battlefield, David has indeed given Goliath an almighty shock. But, make no mistake, Russia is still a daunting adversary.

One senior European diplomat who understands Putin is convinced that the Russian president has no interest in negotiating any settlement. Rather, he thinks, Putin is using this moment to regroup and resupply, ready for another, potentially more devastating assault. Were hopeful Westerners at risk of underestimating Russia's military chances, I asked? Yes, he nodded.

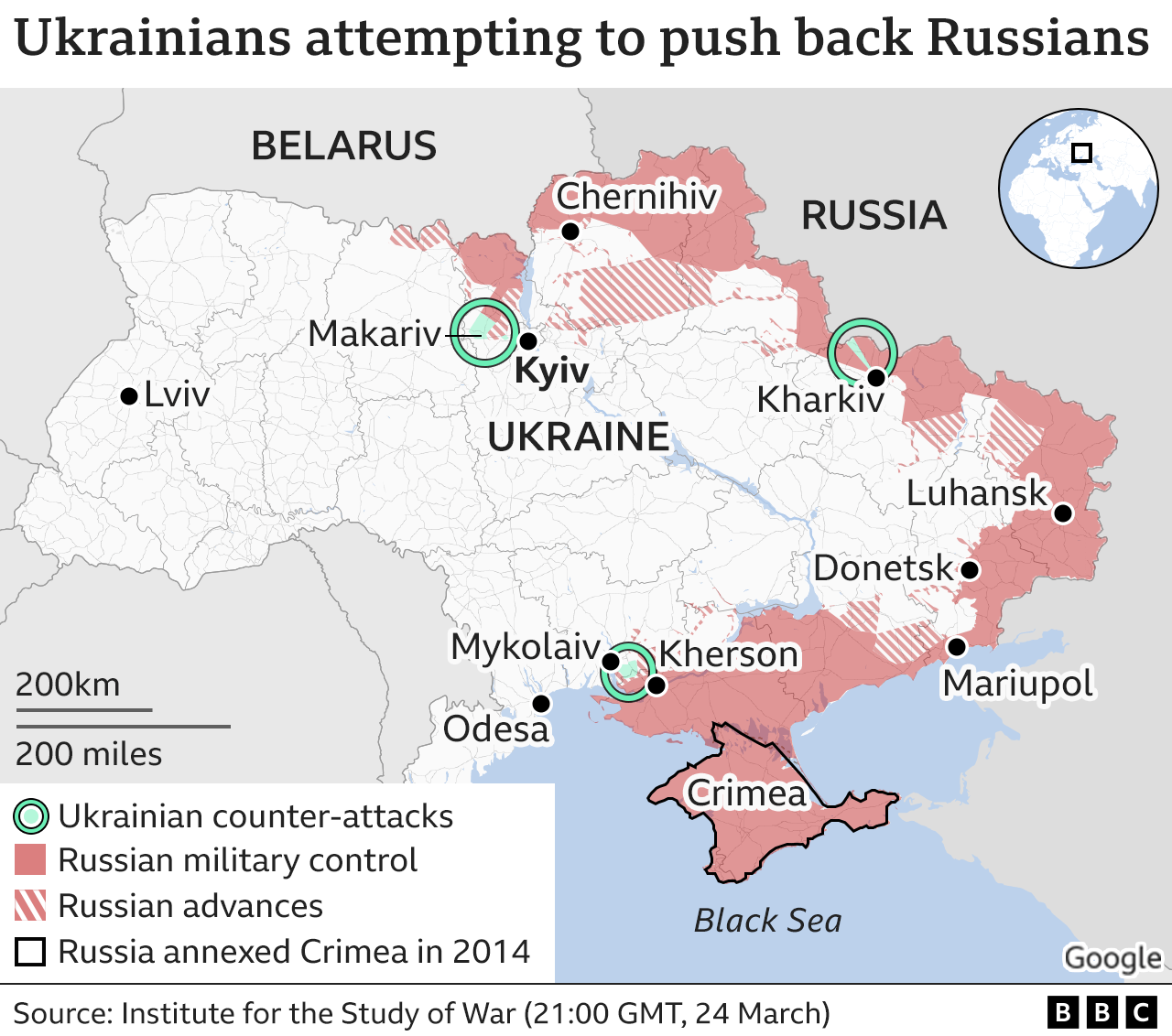

Ukraine campaign map on 24 March

Russia's military boasts 900,000 active duty troops and two million reservists - more than eight times that of Ukraine. It still has a massive arsenal and a satellite state in Belarus from which it can draw more troops, as well as the ability to recruit mercenaries from countries like Georgia, or Syria. It has cyber warfare capabilities it has not yet fully unleashed. It has 4,500 nuclear weapons it has threatened to use, and chemical weapons that the West has warned it might.

The Russians have performed much worse than anyone expected, but they have made some territorial gains, making slow but steady progress around Mariupol and threatening to cut off Ukrainian forces near the breakaway eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. Often, this progress has come by flattening civilian neighbourhoods. Ignoring or diminishing those gains, or the remaining power of the Russian military, won't help Ukraine. Indeed it could hurt it.

The Ukrainians' success depends on two things, their own phenomenal courage, and, just as critical, the steady supply of military hardware that it's getting from Western countries. If those countries, or the public in those countries, start for a moment to think David has beaten Goliath then the flow of weapons could slow or stop. That would be catastrophic for the Ukrainian resistance.

President Biden has spent this week in Europe shoring up the Western alliance. But there's a growing recognition this fight will go on for longer than either Russia or the West anticipated. The Ukrainians may need arms supplies for months to come. The alliance will need to keep its resolve in order to match Putin's determination.

This is no time to be unrealistic. Wide-eyed realism will help Zelensky more than wishful thinking.

- Published1 March

- Published24 March 2022

- Published22 March 2022

- Published20 March 2022