Katty Kay: Why inflation in US is bad for Ukraine

- Published

Boy, did I need to get out of the bubble. I've been in Washington DC since the invasion of Ukraine and it's distorted my perspective on America. A few days in Florida have been a healthy wake-up call.

Washington is a city that's heavy on foreign policy experts. Between the US state department, the foreign embassies, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the dozens of think tanks that specialise in national security, it's a town that lives and breathes global affairs.

It is easily the most international city I've ever lived in, and I've clocked up a few around the world. My friends here include Venezuelans, Senegalese, Argentinians, French, Italian, Indians, Canadians, Trinidadians. Most of them are engaged in public policy in some way.

So, living in Washington, it's easy to forget that the rest of this huge country isn't consumed with world events. And for the past few months the capital of the world's superpower has been obsessed with one issue, and one issue only, Ukraine. In a way that I have never seen here.

My neighbour, a former Pentagon official, is flying a very large Ukrainian flag from his second floor window. It flutters down half the front of his tall house. A couple of blocks away some concerned Washingtonians have repainted their huge garage door bright yellow and blue. Colourful, if not subtle. The Ukrainian embassy is a five-minute walk from my front door. Its front steps are littered with bouquets of flowers, supportive messages, and, rather incongruously, the odd teddy bear.

These kinds of gestures won't make any difference to Ukrainians themselves of course, but they are a useful way to gauge local sentiment. As is what the US press chooses to cover.

I'm fortunate to appear on the US TV network MSNBC as a commentator on current events. It's a role I've had for 15 years, since the war in Iraq. In all that time, all through Iraq and Afghanistan, I've never known US cable channels devote so much time, for so many weeks in a row, to a foreign story which American soldiers aren't even serving in.

MSNBC, CNN, Fox News all have correspondents in Ukraine, reporting live all day and all night ever since the invasion. They haven't missed a day. US networks have spent a fortune covering this story, and they, like other global news organisations, including the BBC, have done it really well. Even now, Ukraine still regularly leads TV news bulletins here.

This may seem an odd observation to people who don't live in the US. Why wouldn't American television spend the bulk of its coverage on Ukraine? It's a war. It's a huge, important story. Perhaps the defining story of our time.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky speaks to US Congress

Trust me, it's very unusual. Especially since it's not clear how much American audiences beyond the rarefied world of Washington are really interested.

A poll by the University of Maryland suggests Americans are following events closely, support Ukraine over Russia and approve of sending military help to Kyiv. Last weekend churches in small towns across the US sent Easter prayers to Ukrainians.

But how much are Americans prepared to sacrifice?

That same polls suggests a healthy majority do not support sending US troops, and a third don't think inflation is a price worth paying to help Ukraine. The poll was conducted from mid to late March and the price of energy has only risen since then.

Another poll by Quinnipiac University, released on 31 March, shows inflation outstripping the war as Americans' top concern - by a long way. Thirty per cent of adults surveyed in the poll said high prices are their top priority, only 14% said the invasion of Ukraine.

This may explain why in Florida the only stripe of blue and yellow I saw was the sunny meeting of sky and sand. I didn't see any "We stand with Ukraine" signs or Ukrainian flags taped to apartment windows. I imagine there are a few somewhere, but we drove through several neighbourhoods and didn't spot any.

What concerned Floridians I spoke to was the high price of petrol and food, and the lack of rain. Two friends told me rather ruefully that they hadn't really focused on the war and felt disconnected from it.

That's not a good sign for either the White House or Ukraine.

Chris Jackson, a senior vice-president at Ipsos, which has produced another poll (this is the country of opinion surveys) summed it up: "The American people are supportive of Ukraine, up to a point."

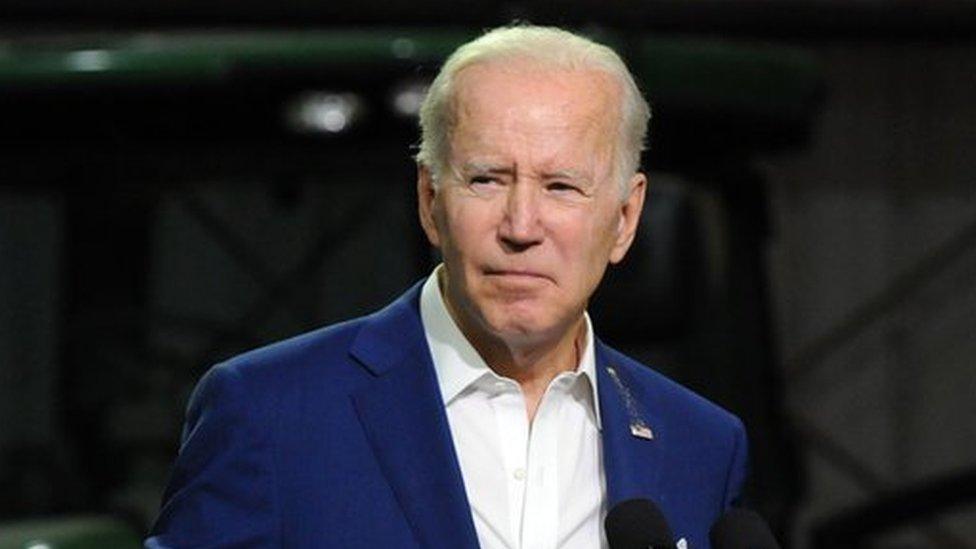

Where that limit of support lies may well depend on the high price of petrol. So far polls suggest Mr Biden gets more of the blame for that than Mr Putin. The longer the war drags on, the higher food and energy prices will rise in the US.

Early in the war Mr Biden told the American people that they would indeed feel the cost of this war - he said he was not going to "pretend this will be painless". But he framed it as an existential choice: "If we do not stand for freedom where it is at risk today, we'll surely pay a steeper price tomorrow." That was back on 15 February, when most people assumed this would be over quickly. Two long, brutal months later, can the president sustain the nation's will to sacrifice, and for how long?

We've seen in the ongoing French election that politicians who ignore local issues to focus on the Ukraine conflict do so at their peril. Marine Le Pen surged in the last two weeks of campaigning before the first round of voting in France in large part because she talked a lot about, you got it, the high price of petrol and food. President Macron had spent most of the campaign telling voters how busy he was managing France's response to the war.

US mid-term elections - where control of Congress will be decided - are now six months away, but US officials warn the war in Ukraine will drag on longer than that. Soon those timetables will collide.

So while the Biden administration is sending more weapons to Ukraine, the administration is also making a concerted effort to talk publicly about domestic issues.

Last week the White House dispatched a senior domestic policy adviser, Susan Rice, to appear on TV shows to announce a new gun control initiative. At the end of an interview, I asked her about the war. Rice used to be the US Ambassador to the United Nations so it seemed a fair question since President Zelensky had been scathing about the global body. But, tempted though she said she was, Rice wouldn't answer the question. Her brief was to talk solely about US domestic policy, not Ukraine. It was a bit awkward, and quite telling.

A Ukrainian soldier holding a Javelin missile during exercises in 2021

The family and I are back in Washington now, nursing a nagging feeling that none of this bodes well for Ukrainians.

Ukraine needs American politicians to continue to feel it is worth spending billions of dollars on weapons for a fight that is 5,000 miles away. For that to happen, it needs those TV editors to continue running news reports about the war. If the audience loses interest, if ratings fall, then the story will start to slip.

The Ukrainian refugees who have come here have been welcomed but there just aren't very many of them. It's not like Poland, or other European countries, where millions of refugees are bringing personal tales of suffering that make the war seem closer. Nor does the existential conflict between democracy and autocracy resonate so much outside the policy hothouse of Washington.

I have found that Americans are, by nature, extremely generous people. They certainly don't want Ukrainians to suffer. But this is a big country, with big problems of its own, not least the fact that right now it is costing people twice as much as they usually budget just to drive to work. Note to self: get out of town more often.

Related topics

- Published21 April 2022

- Published12 April 2022

- Published9 March 2022

- Published13 April 2022

- Published26 January 2023