Nova Scotia shooting: First-hand accounts heard in probe of Canada tragedy

- Published

Flowers lay at a crime scene at the side of the Plains Road April 2020 in Debert, Nova Scotia

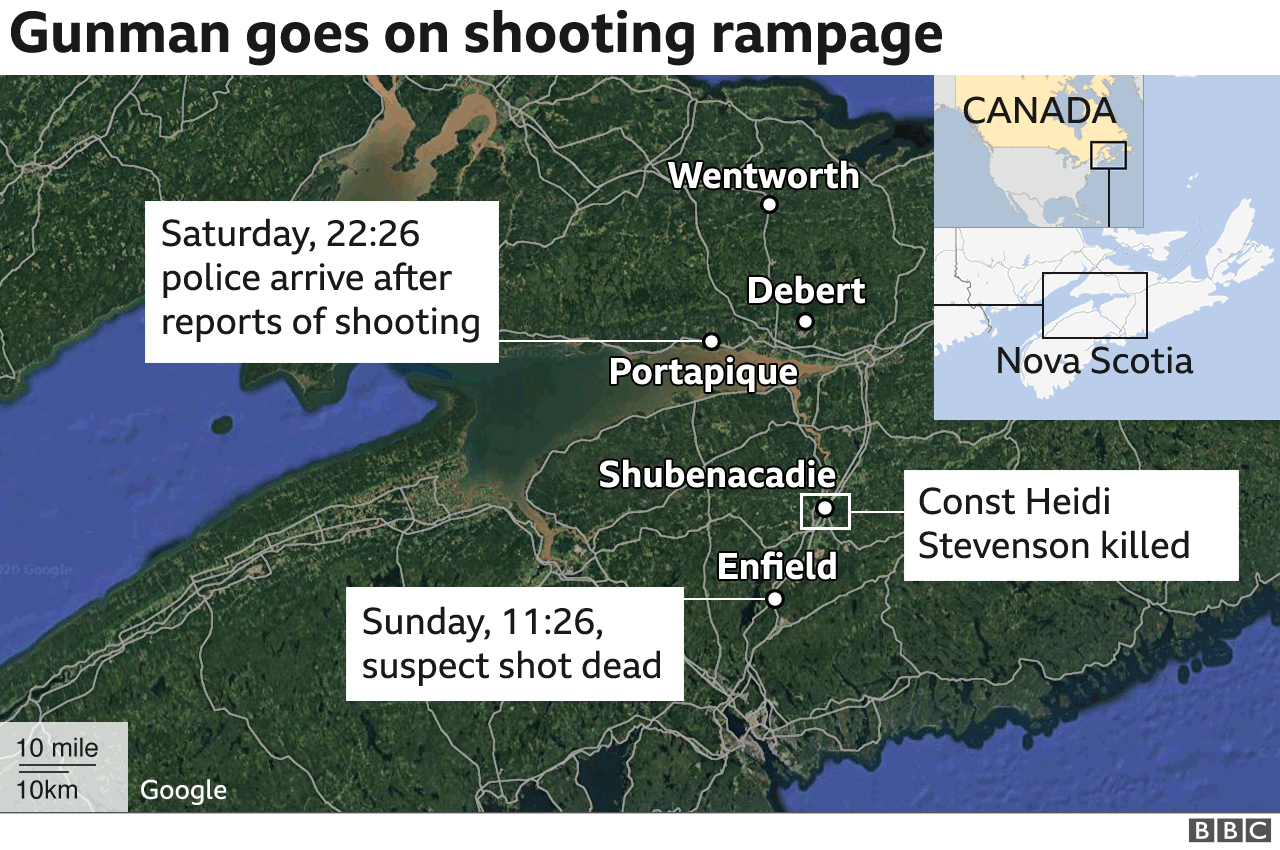

In April 2020, a gunman posing as a police officer went on a shooting spree in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

It left 22 dead, including a pregnant woman, a primary school teacher, a 17-year-old teenager and a police constable. A public inquiry is now looking into how Canada's worst mass shooting unfolded.

First-hand accounts from responding officers, as well as witnesses and experts, have helped paint a picture of a "vindictive" gunman who methodically killed his victims, sometimes setting their homes ablaze and shooting their pets.

But despite the details from their statements, the joint federal and provincial inquiry has left many questions unanswered at the halfway point of its public investigation.

Warning: This story contains disturbing details

The inquiry, which launched in October 2020 amid fierce public pressure, has shed new light on what happened when Gabriel Wortman, a 51-year-old dental technician, went on a 13-hour rampage across some 100km of the Nova Scotian countryside.

Public hearings began in February this year.

Attorney Sandra McCulloch, who represents some of the families of Wortman's victims, told the BBC that, at this point, many are concerned it is not "digging in deeply enough" into the events of 18-19 April 2020.

"They want to know what happened, for the good or for the bad," she said.

In the months since the investigation began, a slew of details have emerged. Here are some of them.

'He has a cop car'

The carnage began on a Saturday evening, in the seaside community of Portapique, which has a year-round population of just about 100 people and 30 homes, no sidewalks, and no street lights.

Thirteen would die in the rural enclave over a 40-minute period, while another nine would be killed the next day.

The first 911 call to police came from the home of Greg and Jamie Blair.

According to inquiry documents, Jamie called 911 at 10:01pm local time on Saturday, to say that a man she identified as "Gabriel" had just shot her husband outside and had parked a fake police car in their driveway.

"There's a police car… it's decked and labelled RCMP, but it's not," she said, according to a transcript of the call.

Wortman then entered the home and killed her in her bedroom while she was on the phone with 911. Her two children, ages 9 and 11, were hidden nearby.

They escaped to their neighbour's home, again calling police at 10:16pm, and repeated that the attacker was driving "a police car".

Despite multiple warnings from witnesses and others about the fake cop car, it was only at 10:17 am the next day - more than 12 hours later - that police posted a public warning about the replica RCMP cruiser on Twitter.

The fake cop car may have helped Wortman avoid detection, police said after the shooting, and the families of some victims have said it caught their loved ones unawares.

Inquiry investigators heard that police wrestled with how to release the image of the vehicle, external without causing panic and overwhelming 911 services.

Police tweeted that they believed a police car was being used by the gunman

Wortman owned multiple vehicles. Some he set fire to on Saturday night, some were registered under a company name. He also owned more than one decommissioned police car, which created confusion among investigators.

Since the shooting, a moratorium on the sale of surplus police cars has been put in place in Canada.

'I mean, it's a war zone'

The inquiry also heard from the first officers on the scene in Portapique, PC Stuart Beselt and his colleagues, constables Adam Merchant and Aaron Patton, who described the scene as a "warzone".

The police officers had been patrolling different parts of the county and weren't sure what they were heading into as they rushed towards the rural community, following a call from dispatch, barrelling along highways at over 100km/hour.

They arrived at around 10:30 pm, shortly after the call from the Blair children, to the sound of gunshots and the sight of multiple fires burning throughout the community, including the perpetrator's own cottage.

Realising they were dealing with an active shooter the three officers dressed in body armour, armed themselves with carbines - or long guns - and began to look for the gunman on foot. They feared that a search in a police cruiser would have made them vulnerable, they told the inquiry.

They having to use Google Maps on their phones to orient themselves in the pitch-dark woods, finding bodies as they chased the sound of gunfire.

They were the only police on site for some 90 minutes, as RCMP was unable to track officers on site with GPS and there was concern police could accidently shoot each other.

And there was risk of ambush from the unseen gunman.

They had a close call when they spotted a flashlight in the woods they thought was Wortman's.

In fact, it was a resident, Clinton Ellison. He had gone out looking for his brother, Corrie, only to stumble across his body.

Clinton saw the RCMP flashlight and turned off his own, fearing he'd been spotted.

The three constables also checked on the Blair children who hid with two other who had lost their mother that night.

Leaving them and going after the shooter was "the single hardest decision that we made that night," said PC Patton. The four children were evacuated shortly after midnight.

In the end, the three constables never came face-to-face with Wortman in the four hours they spent in Portapique.

The commission believes he left Portapique using a private dirt track with access to a nearby highway around 10:45 pm local time, evading authorities.

'I wanted to know who we were looking for'

RCMP dog handler Craig Hubley went into work early on Sunday morning, after getting a text message from his sergeant about the active shooting case.

At the command centre were photos of the gunman, and PC Hubley recalled "trying to burn them into my mind's eye".

"I wanted to know who we were looking for," he told the inquiry.

His colleague, Constable Ben MacLeod, had been in Portapique for hours.

PC MacLeod said that by Sunday morning there was speculation that the gunman may have killed himself somewhere in the woods overnight, but this proved wrong.

It's believed he actually spent about six hours overnight in an industrial park in a community about 24km (15 miles) away.

He began his killing spree again sometime between 6:35 am and 9:00 am on Sunday morning in Wentworth, a hamlet about 45km from Portapique. There, he shot Alanna Jenkins and Sean McLeod and set their home on fire before killing their neighbour Tom Bagley.

There had been a "lull" in the violence overnight but when the emergency calls began to come in once more, "we all knew" the gunman "had gone active again", PC MacLeod said.

More calls soon came in.

The shooting of two more victims - Kristen Beaton and Heather O'Brien - left PC Hubley feeling "defeated... [when it] seemed like we were seconds behind him," he told the inquiry.

CCTV footage shows PC Hubley as he spots the gunman at the petrol station

Then, as he and PC McLeod stopped to fill their truck at a petrol station, noticed the man who had driven a grey hatchback car parked next to them.

"He was wearing a white t-shirt and he looked very sweaty, very rundown," he recalled. "Like he had...lost a fight or had just finished a big one."

He realised he was staring at the face he had studied that morning. At that moment, the gunman lifted a pistol. He lifted his own weapon and fired multiple rounds.

Five firearms were later discovered in Wortman's car, including an RCMP-issue Smith & Wesson he had taken from one of his victims, RCMP Constable Heidi Stevenson.

Wortman did not own a firearms licence and had smuggled some of the weapons across the border from the US, according to inquiry documents.

Some of the victims of Canada's largest mass shooting

Who are the victims?

Greg and Jamie Blair

Jolene Oliver, Aaron Tuck, and their daughter, Emily Tuck

Joy and Peter Bond

Lisa McCully

Frank and Dawn Gulenchyn

Joanne Thomas and John Zahl

Corrie Ellison

Alanna Jenkins and Sean McLeod

Tom Bagley

Lillian Campbell

Kristen Beaton

Heather O'Brien

Constable Heidi Stevenson

Joseph Webber

Gina Goulet

Lessons learned and still to be learned

The inquiry is currently looking into why a province-wide emergency alert, which would have sent warnings to people's phones, radios and televisions, was never sent to warn residents about the danger.

Nova Scotians have questioned the police response, which relied on social media to alert residents of the manhunt for the gunman.

Attorney Ms McCulloch also said that the families she represents are anxious to hear from the gunman's common-law spouse, who was severely beaten by the shooter and physically restrained the first night of the attack after an argument with Wortman.

She was able to escape and fled into the woods, where she hid throughout the night.

Police had initially charged her and two others with unwittingly helping provide the killer with the guns and ammunition but the case was later referred to restorative justice, meaning the charge will be dropped after she completes a government programme.

The move cleared her to testify to the inquiry.

Related topics

- Published24 July 2020

- Published17 July 2020

- Published24 April 2020