The sudden silencing of Guantanamo's artists

- Published

A sketch by Muhammad al-Ansi, stamped with approval for release from the prison at Guantanamo

A few weeks ago, Khalid Qasim got some news he'd been waiting 20 years for. He had been cleared for release from the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

Qasim has been in Guantanamo nearly half his life, aged 23 to 43. Like almost all the men sent there, he has never been charged with a crime.

His release order does not mean freedom, yet. It is merely the starting gun on a long process of resettlement that, going by previous resettlements, could take years. Where he will be sent, neither he nor his lawyers know.

While he waits, Qasim will paint.

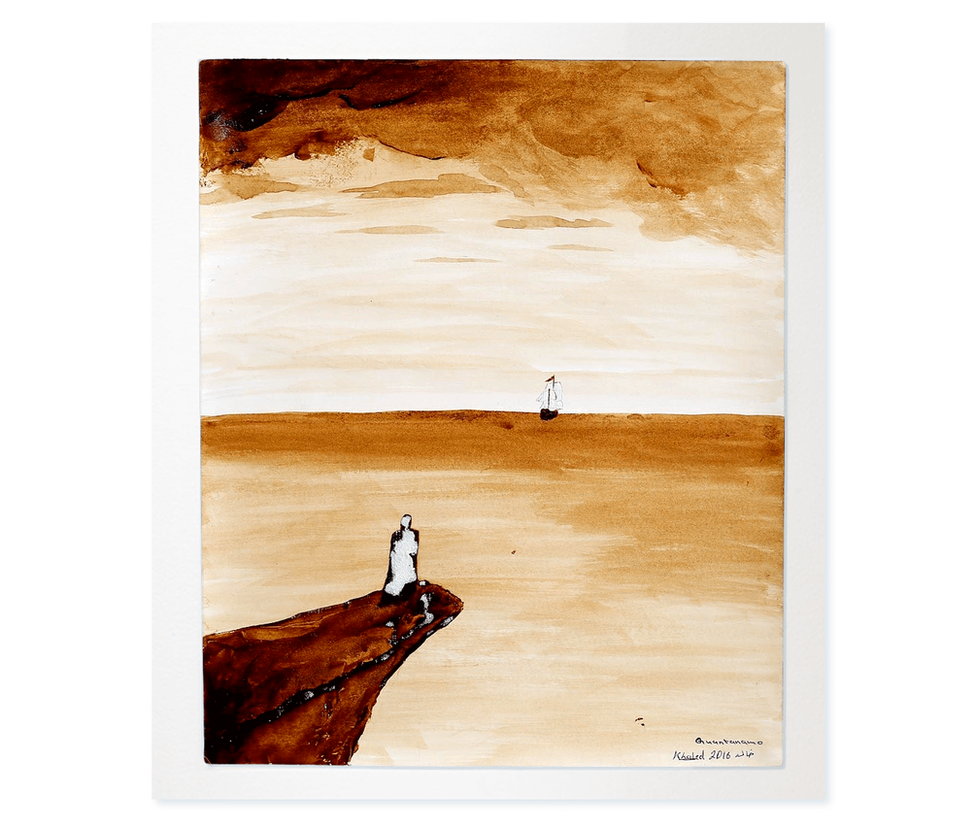

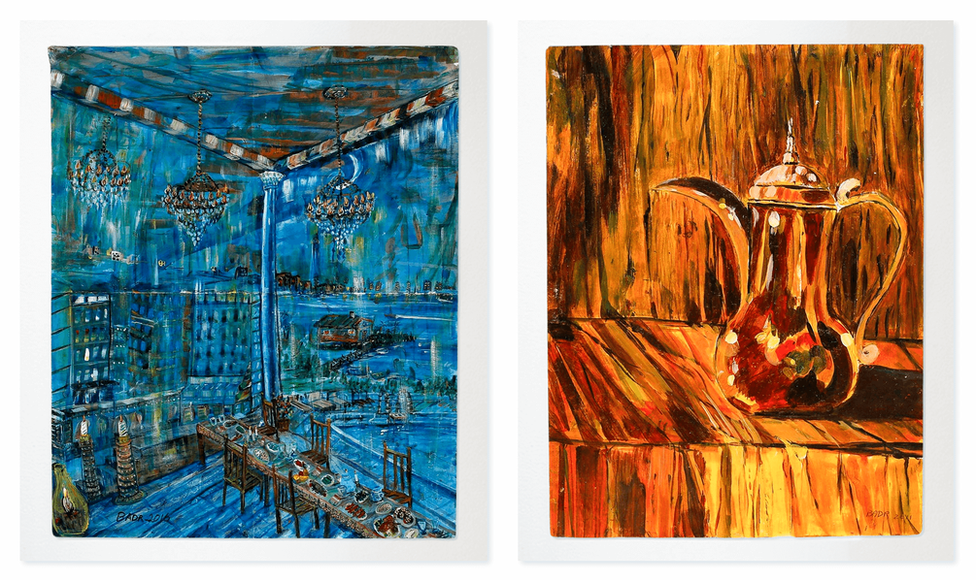

A painting by Khalid Qasim of a remembered scene from his home in Yemen

During his long detention, Qasim has created scores of intricate paintings and other artworks, from seascapes, to scenes of fire, to a series of lone candles that commemorate the men who died in Guantanamo.

"The easiest way to explain it is that it's a way of telling others about what I feel," Qasim said, via his lawyer. "It's a feeling I have. It's a part of me. I'm putting Guantanamo on canvas."

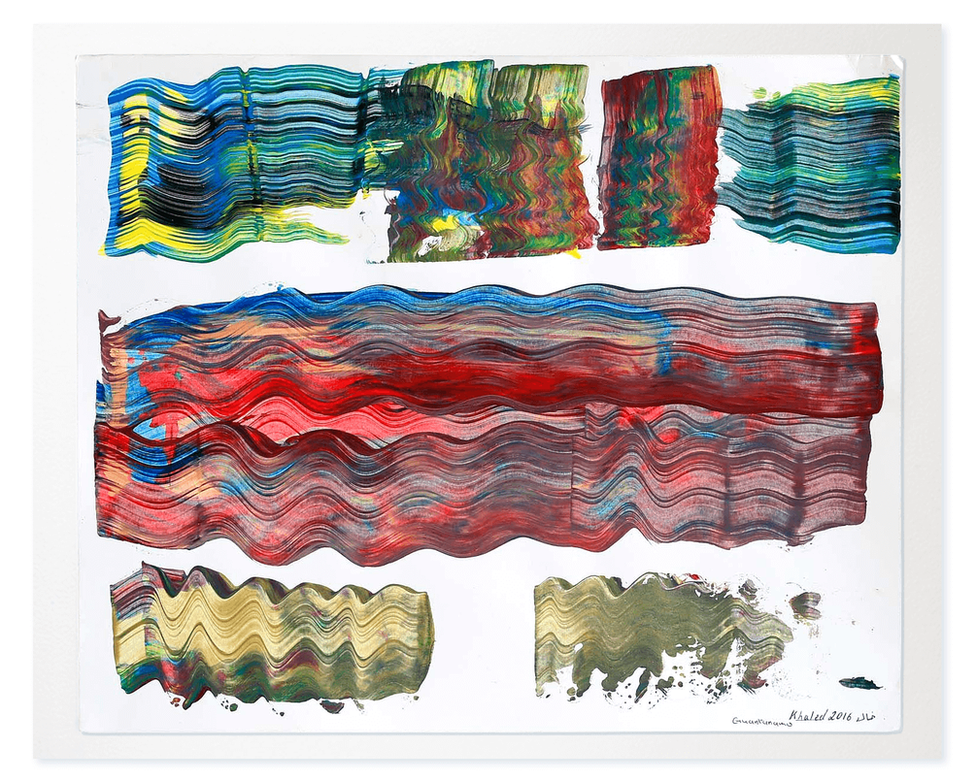

Qasim rarely puts Guantanamo on canvas in a literal sense. He is drawn to images of the sea, to images of ships and trees. He paints abstracts in vivid colours and still life scenes with deep blacks and dark expanses. He has used coffee and gravel from the exercise yard to create textures and ready-to-eat meal boxes to make mixed-media work.

"This is my life," Qasim said, of his art. "It was my life here."

But when Qasim is transferred out of Guantanamo, in months or years, he will not, as things stand, be allowed to take his art. It will remain the property of the US government, which may store or destroy it.

Keeping his art in Guantanamo would be "the same as keeping me here", Qasim said.

"The art I made is me," he said. "If they keep my art here, my soul will stay here."

Khalid Qasim, 2016

This was not always the case. Until the end of 2017, Guantanamo detainees were allowed to take their art with them when they were released, or give it to their lawyers to take out.

The artists could bring their work to meetings with their lawyers, who would submit it along with their meeting notes to a team which vetted it for classified material or national security issues.

Artwork deemed sensitive - paintings depicting torture, for example, or hunger strikes - was not allowed out, but otherwise the work was given back to the lawyers to take away.

Then in late 2017, under the Trump administration, it became clear that art was no longer being allowed out. Like lots of things in the world of Guantanamo, there was no official notification to the lawyers, no memo. Artwork was all of a sudden simply bounced back from the vetting team to the detainees.

Khalid Qasim created nine solitary candles for the nine men who died in Guantanamo

Then the vetters at Guantanamo began marking the descriptions of the art in the lawyers' notes as classified. "Now they are not even allowed to bring the art to the meetings," said Mark Maher, who represents Khalid Qasim. "It's very frustrating for the men."

In response, four lawyers penned a letter to military officials asking for the ban to be overturned - pointing out that convicted US state and federal prisoners were permitted to make, send out, exhibit and sell their art. The lawyers got no reply.

"If they have a reason I would love to hear it," said Maher. "I don't know what the justification could be for not allowing this art out into the world. We have requested that the men be allowed to leave with it, and the response we've had has been silence."

Inside the walls of Guantanamo, Moath al-Alwi has finished a new ship. It is called Eagle King, and it is his biggest and most intricate yet, with anchors, decks, an array of masts and sails and an eagle atop the bow rigging with its wings spread wide.

Al-Alwi, a Yemeni, has for the past few years been making remarkable model boats and galleons from found prison materials - sails cut from old T-shirts, rigging from unravelled prayer caps, a steering wheel made from a bottle cap, connected by dental floss to a shampoo bottle rudder.

Before Eagle King was complete, al-Alwi's biggest model was Giant. When he finished Giant's sails and fastened its rigging, "the most beautiful thing happened", al-Alwi said, in a conversation relayed by his lawyer. "I felt as if I were in the middle of the ocean. I felt waves hitting the ship from every direction, and I felt I was rescuing myself."

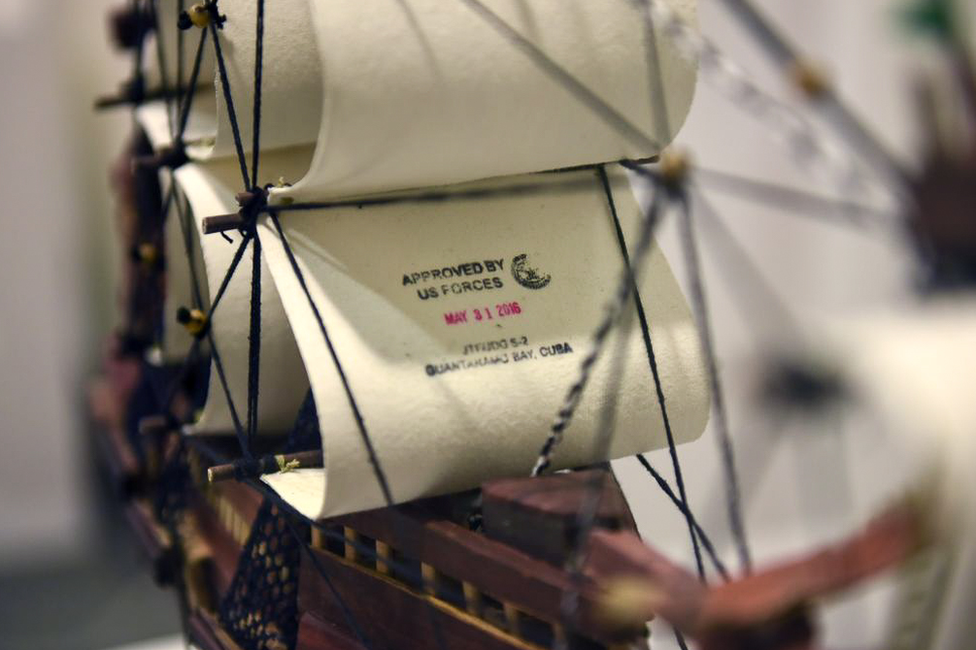

Giant, by Moath al-Alwi, on display at the John Jay College, New York

Al-Alwi was cleared for release earlier this year, but he cannot go home because the US deems Yemen unstable, so a third country will have to be found. He will likely follow other former detainees into a restrictive environment in an unfamiliar country, while his models remain in Guantanamo or are destroyed.

As well as Eagle King, al-Alwi has completed work on another new boat, this one called Hope. No photographs of it exist, and his lawyer's descriptions of it in her notes have been classified. But al-Alwi was able to describe it in an unclassified phone call. It is smaller than his large galleons, he said. The colours are softer - pastels. He has drawn flowers and doves on the sails.

"Despite being in prison, I try as much as I can to get my soul out of prison," he said. "I live a different life when I am making art; it makes me live within my soul. It makes me feel free."

A Guantanamo release stamp on the sail of a ship made by Moath al-Alwi

The trouble began with a show in New York. Before the rule change in 2017, Al-Alwi's lawyer, a New Yorker named Beth Jacob, had been taking large volumes of art with her when she left Guantanamo, from al-Alwi and her other artist-clients.

Ark was the first model she took out. When she submitted it to be vetted, unlike with paintings there was no convenient back side of a canvas to stamp, so the prison staff used one of the ship's sails. It did not bother al-Alwi. "I wanted the prison stamp to be clear on the sail so people would know the ship comes from Guantanamo," he said.

Jacob bought an extra seat on her commercial flight home from Miami and contacted the airline in advance to clear it, but she was still thrown off the flight with the model - told only that the pilot refused to fly with it.

Ghaleb al-Bihani, 2015

Next came Giant, which was even bigger. Instead of attempting to board a commercial flight back to New York, Jacob drove Giant to her daughter's tiny studio apartment in Miami Beach, where it sat for months in its carry case, wrapped in blankets, a seat for the cats, until an Israeli clarinettist from her daughter's orchestra agreed to drive it up north, as he was going anyway.

The artwork slowly accumulated in Jacob's office, out of sight, until 2017, when she invited a friend of a friend, Erin Thompson, a professor of art crime at John Jay College in New York, to take a look.

"I assumed it would be work about Guantanamo, scenes of life there. Instead I'm seeing all these beautiful melty, dreamy landscapes and seascapes," Thompson recalled. "I had to know more."

So Jacob put a call out on a Guantanamo lawyers' email group, and other lawyers with filing cabinets full of art responded. Thompson decided to put on a show at the college. "I thought the art was beautiful and I wanted other people to have the same reaction," she said.

A ship in stormy seas, painted by Sabry al-Qarashi

Thompson's exhibition brought together 36 pieces of work by current and former detainees. Al-Alwi's model ships were there, and some of Qasim's seascapes. The exhibition was modestly attended. "The show opened with like, two newspaper articles. I was doing things like begging my dentist to come," Thompson said.

Her dentist didn't come, but the US Department of Defense took notice, and apparently became concerned that some of the art was available for sale. (The exhibition catalogue stated that the only work potentially available for sale was by former, not current, detainees.)

About two weeks after Thompson's exhibition, the Guantanamo art policy suddenly changed. A Pentagon spokesperson confirmed to the Miami Herald, external at the time that the change stemmed from a concern about sales, but otherwise the government has said virtually nothing. The Pentagon told the BBC only that detainee art was "considered the property of the US Government and, as such, will remain in the custody of the JTF [Joint Task Force - which runs the prison] at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility".

Abstract, Khalid Qasim, 2016

Since the ban was put in place, one detainee has been able to leave the prison with his art. The rule was waived for Ahmed al-Darbi - a confessed al-Qaeda member - in exchange for his co-operation testifying, the Pentagon said at the time. But for the others, their work remains the property of the government. What puzzles Thompson and Jacob is why the authorities would be concerned about former detainees making money. The whole idea was that the men were supposed to start supporting themselves after release, Jacob said. "If a guy gets a job, are they worried about him making money? If a guy sells a picture, isn't that a plus?"

Neither the lawyers nor Thompson ever heard from the government about sales. Thompson did hear from some relatives of 9/11 victims. She got some complaints, she said, but also encouragement. A group of 9/11 widows got in touch to thank her for getting the prison back in the news, at a time when people had all but forgotten about it, and Thompson took them on a tour of the gallery.

No one would have taken any real notice of the exhibition if the defence department hadn't reacted by banning artwork leaving the prison, Thompson said.

"Of course then it became a big story," she said. "And lots of people came to the show."

Djamel Ameziane, 2010

There are still 36 detainees in Guantanamo, and they are still allowed to make art. But they cannot show it or keep it. A group of former detainees is preparing to publish an open letter on their behalf to the US president, Joe Biden, asking him to overturn the Trump-era ban.

"Art helped us to survive at Guantanamo, to overcome the hardship and difficulties. It was our only escape from the prison's pain and loneliness," the letter will say. "We painted the sea, trees, the blue sky, ships, we painted our hope, fear, dreams, and our freedom."

The detainees have the support of various artists and curators. "It makes a huge difference if the public understands that these men are poets, painters, writers, thinkers, that they are people," Laurie Anderson, the American artist, told the BBC.

"They have experienced great suffering and they have processed that suffering and found a way to express it," she said. "And it benefits the American public to see that."

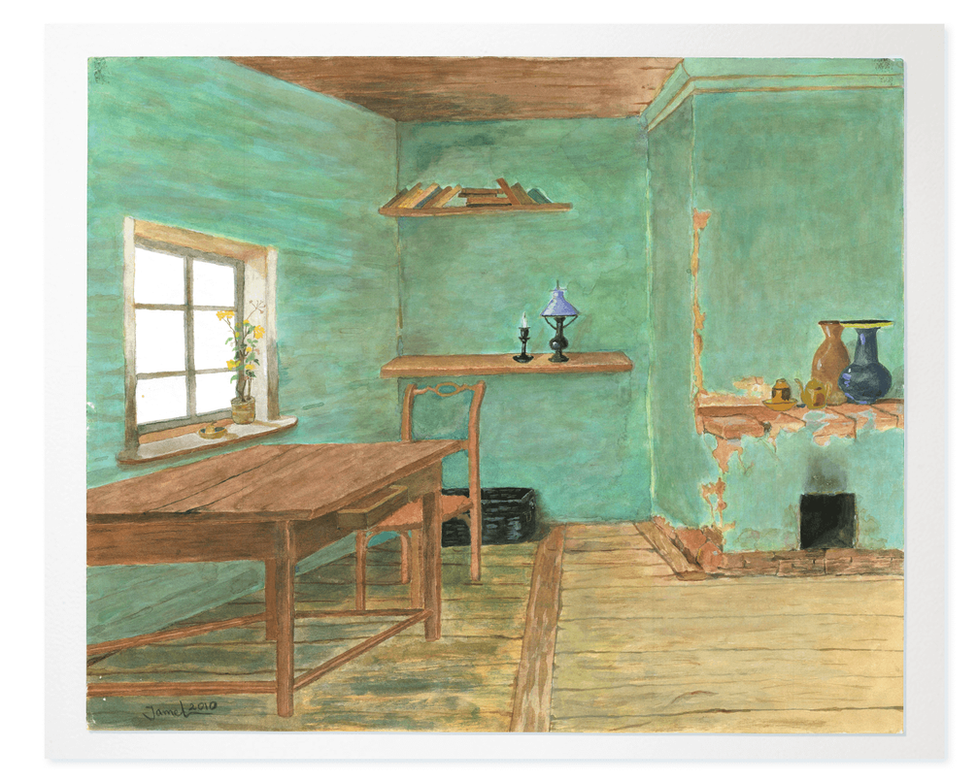

Ahmed Rabbani, a 20-year detainee, paints tea scenes, where he can imagine gathering with family

Inside Guantanamo, the ban has had a discouraging effect on the artists, said Ahmed Rabbani, a 20-year detainee and painter who is awaiting transfer. "Before the rule changed, I would make one piece a week, sometimes more than one a week," Rabbani said. "Now when I create a new piece, I get disappointed and discouraged. If I can't take it with me, why make it?"

Rabbani is a skilled painter who has painted vivid scenes of tea settings with no people present - scenes he can populate in his imagination with his absent friends and family. Sometimes there are empty plates, references maybe to his hunger strike protests against torture. And, of course, he has painted the sea.

Al-Alwi, the shipbuilder, has recently begun to paint too. He has created a series of four pieces he calls The Story of My Imprisonment. No one outside the prison has seen them, but he described them over the phone. He said he had painted a man standing alone on a beach, through various phases of his life, as the moon rose and fell. By the third painting, the man had died. In the fourth, a boat finally arrived at the shore.

"When the boat came, they did not find the man, but they saw the tomb and put some flowers next to it," Al-Alwi said. "They left a note that it was too late."

Graphics by Lilly Huynh

- Published13 June 2022