Four states voted to abolish slavery, but not Louisiana. Here's why

- Published

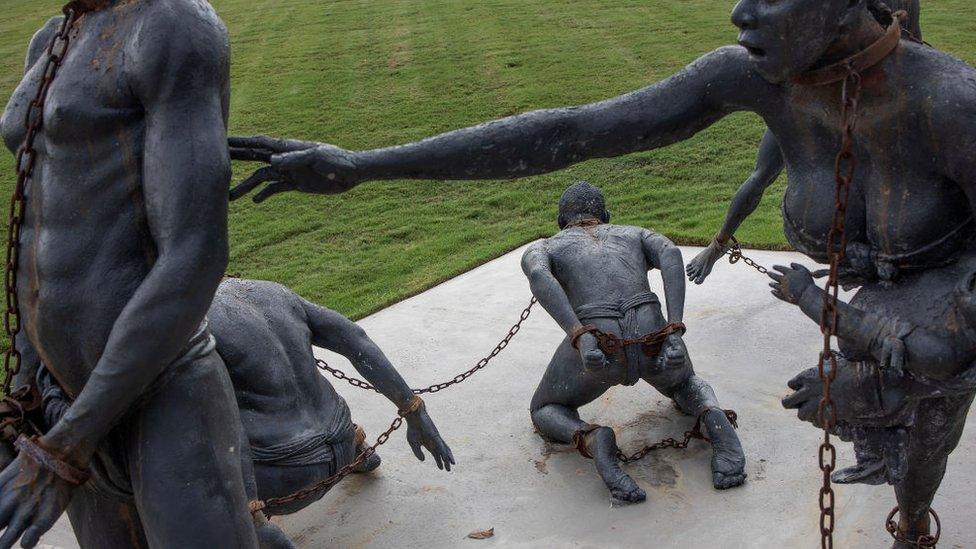

A monument to slaves in Montgomery, Alabama

Four US states have voted to remove language from their state constitutions that said slavery is legal as a criminal punishment.

But Louisiana voted to keep the slavery exception after the legislator who had sponsored the ballot initiative turned against it.

Edmond Jordan said he had realised that the measure could have inadvertently expanded slavery.

Advocates of the initiative say it is needed to prevent prisoner abuse.

They hope to remove the same exemption from the US Constitution's 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery but kept a loophole.

Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont all voted on Tuesday to remove exemptions allowing slavery or involuntary servitude from their state constitutions in an effort to ban slavery entirely.

But with all ballots counted from Tuesday's midterm elections, six out of every 10 Louisiana voters opposed the amendment.

The outcome could enable prisoners to challenge forced labour in the criminal justice system, say legal experts.

Some 800,000 prisoners currently work for pennies, or for nothing at all, according to experts. Seven states do not pay prison workers any wage for most job assignments, and prisoners can be punished if they refuse to work.

So why did Louisiana reject the change?

Mr Jordan, a Democratic state representative for the city of Baton Rouge, says he pulled his initial support for the measure after a closer reading of the proposed law led him to believe that it could have actually expanded protections for slavery.

Currently, the law states that "slavery and involuntary servitude are prohibited, except in the latter case as punishment for a crime".

The proposal he authored would have removed the phrase "except in the latter case as punishment for a crime" and added a clause saying that the measure "does not apply to the otherwise lawful administration of criminal justice".

"Slavery" is currently banned under the law, he says, but the use of the word "latter" in the existing law means that "involuntary servitude" is still technically legal as punishment.

Although there is "almost no difference" between slavery and involuntary servitude, Mr Jordan says, the removal of the word "latter" would have left it saying that slavery and involuntary servitude are both permitted for the "lawful administration of criminal justice".

In an interview with BBC News on Wednesday, Mr Jordan said he pulled his support because he wanted to "do no harm" and that keeping the law as it stands now means "we're no worse off today than we were two days ago". He says he plans to revise the bill and campaign for it to pass in 2023.

Asked if he had concerns that the proposed law could have allowed slavery, he cited the Supreme Court's decision in June to invalidate the national right to abortion after 40 years as established law.

"If you had asked me that question a year ago I would have told you that the likelihood of it being a threat would have been slim to none, because it's banned on the federal level.

"But after the reversal of Roe v Wade - the reversal of things we once thought were well-settled law - I don't want to take the chance on something we think is well settled."

But Curtis Davis III, a former Louisiana prisoner who was pardoned after 25 years when his murder case was re-investigated, said he believes "political horse trading" was at play behind the scenes.

He suspects Mr Jordan and the state's legislative black caucus withdrew support for the measure because the state is one of a handful that still sentences prisoners to "hard labour".

Mr Davis believes that lawmakers were concerned the new language in the charter could have potentially invalidated court sentences handed to thousands of prisoners in Louisiana.

Mr Jordan denies that hard labour contributed to his decision. Prison labour is a multi-billion dollar industry in the US.

Mr Davis says the "lawful administration of criminal justice" wording would have prevented mass releases, and says that it would be a legal issue for courts to decide.

But Mr Davis says he's not disappointed that his state did not change the law.

He said the real goal is to change the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution, which supersedes state constitutions.

In order for the 13th Amendment to be changed, it would require a two-thirds majority from both chambers of US Congress, or by a constitutional convention in which two-thirds of state legislatures vote to support the change.

There are still more than a dozen states that include language permitting slavery and involuntary servitude for prisoners, according to the Associated Press news agency. Several other states make no mention of slavery or forced prison labour.