Why politicians keep misplacing classified documents

- Published

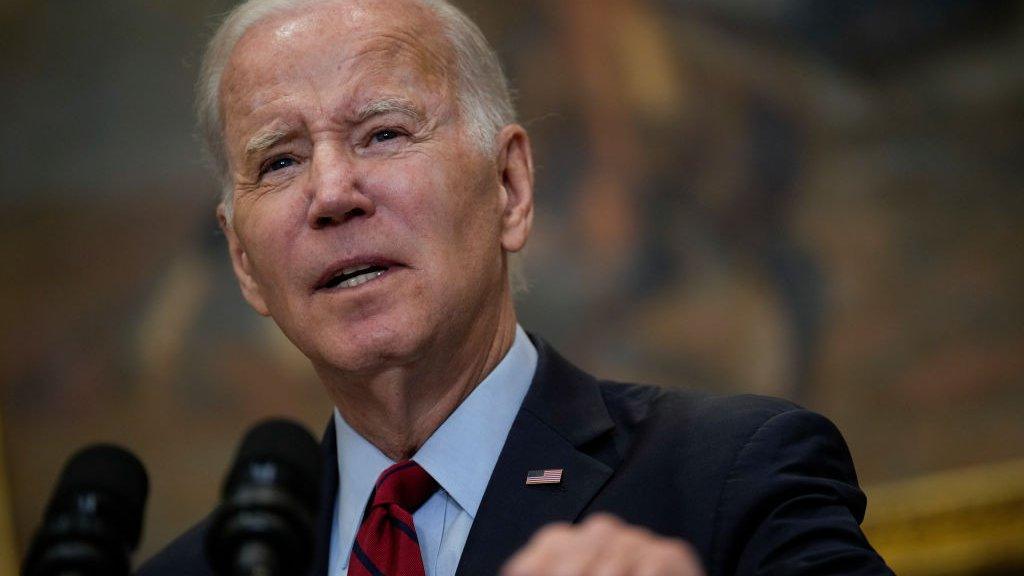

Watch: Biden says documents weren't sitting out on the street

For top US officials, it appears the words "top secret" are sometimes treated as more of a suggestion than a rule.

Former US Vice-President Mike Pence is the latest in a long line of politicians to have classified documents turn up at his home.

Both President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump are currently facing investigations into files found in their possession.

Mr Pence and Mr Biden notified authorities when the documents were discovered. The FBI raided Mr Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate to recover classified and sensitive material, including documents labelled "Top Secret", the highest security classification. The Justice Department has also alleged the Trump team deliberately obstructed their investigation.

But they are far from the first politicians to be found potentially mishandling sensitive material.

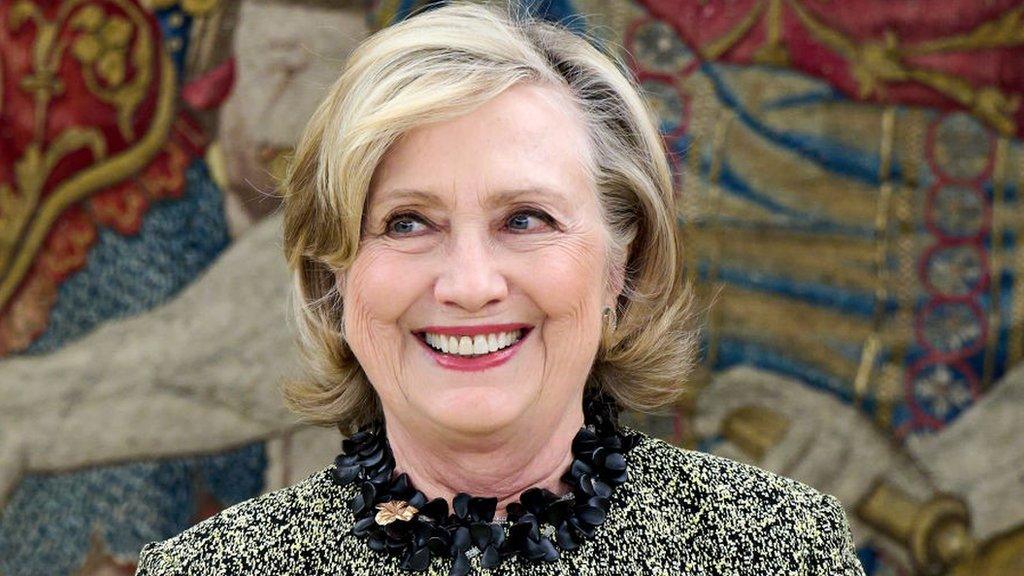

Many statesmen including Hillary Clinton and a former Canadian foreign minister have landed in trouble for not following security protocols.

"Misplacing classified documents is very common, happens all the time," said Tom Blanton, who runs the National Security Archive, an independent repository of government documents based at George Washington University.

Should more documents be declassified?

While it is unclear exactly what was in the documents Mr Pence had in his possession, Mr Blanton said there is a wide range of information that can be classified. Some materials, like travel briefings, may be classified even if they contain mostly public information from news articles.

Such files are supposed to be declassified after a period of time, but because it does not automatically happen, there is inevitably a backlog - which is partly why officials are "drowning" in classified information.

Other classified documents, labelled "Sensitive Compartmented Information" (SCI), contain details that could expose intelligence sources.

Several documents marked SCI were found at Mar-a-Lago, Mr Trump's Florida home, according to photos released by the FBI.

Are Trump's documents different?

But the big difference between others' missteps, and Mr Trump's, is how the mistakes were handled after they were discovered, says national security legal expert Brad Moss.

"You notify the authorities, you make sure that the documents are properly returned to the relevant government entity and taken away from the unauthorised location. That's the way you're supposed to do it," he said.

"What you don't do is what Trump did, which was spend 18 months delaying, obfuscating, obstructing the inquiry."

The search at Donald Trump's home is highly unusual and marks a major step by prosecutors investigating his actions

Mr Moss said that it is not unheard of for people to end up in court if they are caught with documents they should not have.

Under the Espionage Act and other federal security provisions, any unauthorised retention, mishandling or transmission of documents violates the law. But authorities rarely prosecute, save for two reasons, Mr Moss said: Intent or obstruction.

If authorities believe a document was kept intentionally to sell, or leak, the person responsible could face serious legal consequences, as happened in the case of ex-CIA boss David Petraeus.

Petraeus was charged with giving classified documents to his former mistress and biographer. He reached a plea deal with the justice department, avoiding felony charges but getting sentenced to two years probation and a $100,000 fine.

Charges are also likely if the person responsible for the documents obstructs an investigation into their mishandling.

Embarrassing errors

But most of the time, the repercussions of mishandling classified documents are more political than criminal.

Who can forget the revelation in the autumn of 2020, weeks before the election, that Mrs Clinton had stored work emails on a personal server when she was Secretary of State? The FBI investigated, and she was cleared of criminal wrongdoing.

Although her aides were chastised for being "extremely careless", it was found she did not knowingly share sensitive information.

American officials are not the only ones who can be accused of carelessness.

Maxime Bernier, Canada's foreign affairs minister under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, was forced to resign in 2008 after his then-girlfriend went on television and said he had left secret documents in her apartment. The press had a field day.

In 2011, UK minister Oliver Letwin was admonished when a picture emerged of him dumping government documents in the rubbish.

He apologised and an investigation found that none of the papers had been classified. Nevertheless, he was made to sign a pledge to change how he handled personal data.

Why does this keep happening?

Mr Blanton said that part of the problem is the sheer volume of classified documents that passes through top officials' hands. Many of those documents did not even need to be classified or should be automatically de-classified after a few years, he said, but "you get the sense people get blasé about it".

Another problem, according to Mr Moss, is that high-level officials - whether they are the president or a member of cabinet - are often not properly trained in security best practices in the same way that a senior aide may have been. And because of their status and security clearance, they are given unparalleled access to sensitive materials.

When civil servants make an error, they can have their security clearance revoked or be suspended or fired.

But telling the most powerful person in the room they are doing it wrong is easier said than done.

"Better training would fix it, but in reality, that'll never happen," Mr Moss said. "Once you get to that level of authority, you tend to take a very broad view of your powers, and the extent to which anybody can tell you how to do anything."

- Published12 January 2023

- Published20 October 2011

- Published12 June 2023

- Published6 November 2016