Four key findings in Maryland clerical abuse report

- Published

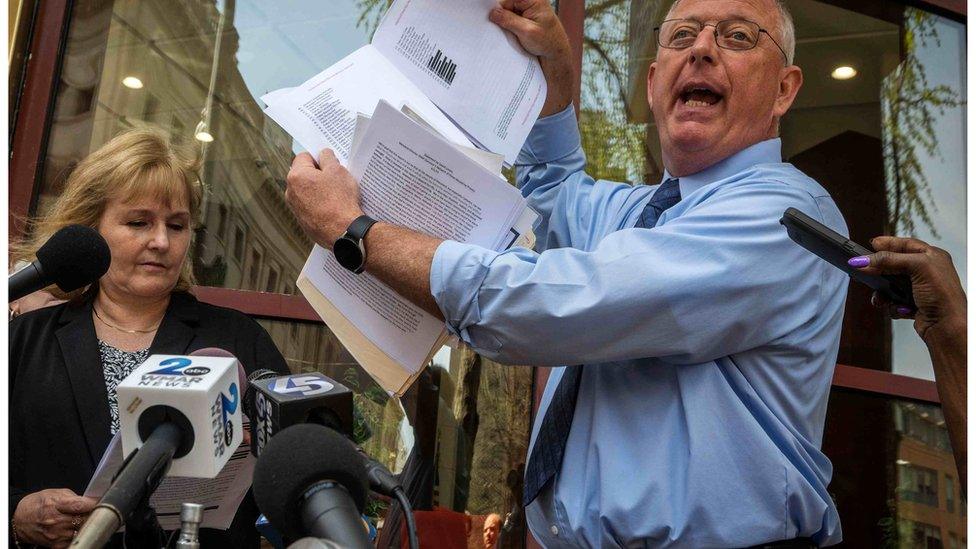

Dave Lorenz, a local advocate for victims of abuse, holds aloft the damning report

More than 600 children were sexually abused by over 150 Catholic priests and others associated with the Archdiocese of Baltimore over the last 80 years, a newly released state report has found.

Maryland's top prosecutor accused church officials of a decades-long cover-up, and a "staggering pervasiveness" of sexual abuse in a long-awaited, 463-page document.

Investigators began their work in 2018 and their report has been met with shock and anger by victims and campaigners.

Baltimore Archbishop William Lori apologised to the victims and vowed that this "reprehensible time in the history of this Archdiocese" would not be ignored or forgotten.

Here are the key takeaways from the report.

The abuse involved hundreds of victims

Hundreds of thousands of documents dating back to the 1940s were examined.

More than 600 children were abused by the 156 people included in this report, wrote Maryland Attorney General Anthony Brown. "But the [actual] number is likely far higher."

Isolated and vulnerable children were often the target of abuse, according to the report.

Often they were young people with close ties to the church - altar servers, choir members, participants in church youth organisations, and those who worked in church housing answering telephones.

"The incontrovertible history uncovered by this investigation is one of pervasive, pernicious and persistent abuse by priests and other archdiocese personnel," said the attorney general at a press conference.

The Church protected the abusers

The report accuses the Baltimore archdiocese of routinely and methodically covering up abuse by clergy in the Catholic church, for decades.

"Time and again, bishops and other leaders in the church displayed empathy for the abusers that far outweighed any compassion shown to the children who were abused," the report said.

The report lists numerous instances of church leaders appearing to protect accused clergy members, rather than holding them accountable.

Abusers remained in post or were moved to another parish, any investigations that did happen were conducted by other clergy and not independent investigators, the report said.

Archbishop Lori said, in a statement posted online, external that the accounts of abuse were "shocking and soul searing".

"It is difficult for most to imagine that such evil acts could have actually occurred. For victim-survivors everywhere, they know the hard truth - these evil acts did occur."

Victims are still feeling the trauma

Jean Hargadon Wehner, who was abused in Baltimore as a teenager by her Catholic high school's counsellor and chaplain, told reporters at a press conference that she's "still angry", the Associated Press reported.

Ms Wehner said her abuser was A Joseph Maskell, who is listed in the report for having abused at least 39 victims. Before he died in 2001, he denied the allegations and never faced criminal charges.

Kurt Rupprecht, who was abused at his parish in Salisbury in the 1970s, said: "We're here to speak the truth and never stop. We deal with this every day. It is our life sentence."

He added in an interview with local media that the primary feeling was relief because now there could be a "social reckoning, a public reckoning".

Terence McKiernan, president of Bishop Accountability, a victims' advocacy group, called the report "a shocking addition to our understanding of clergy abuse of children in Baltimore".

Prosecutions could still happen

Lawyers for the state had previously asked a court for permission to release the report last year.

The request was not granted until last month, after a Baltimore Circuit Court judge ruled that a redacted version could be made publicly available.

This version omits the names and titles of 37 people accused of wrongdoing. The names were obtained from church officials via grand jury subpoenas and are thus considered confidential in Maryland. However, the judge said a more complete version could be released in the future.

Also this month, lawmakers in Maryland passed a bill to end a statute of limitations on abuse-related civil lawsuits which says victims of child sex abuse in the state cannot sue after they turn 38.

The bill, which now sits on the state governor's desk, would eliminate the age limit and allow for retroactive lawsuits.