Mark Bryant counts US shootings. He no longer remembers the names

- Published

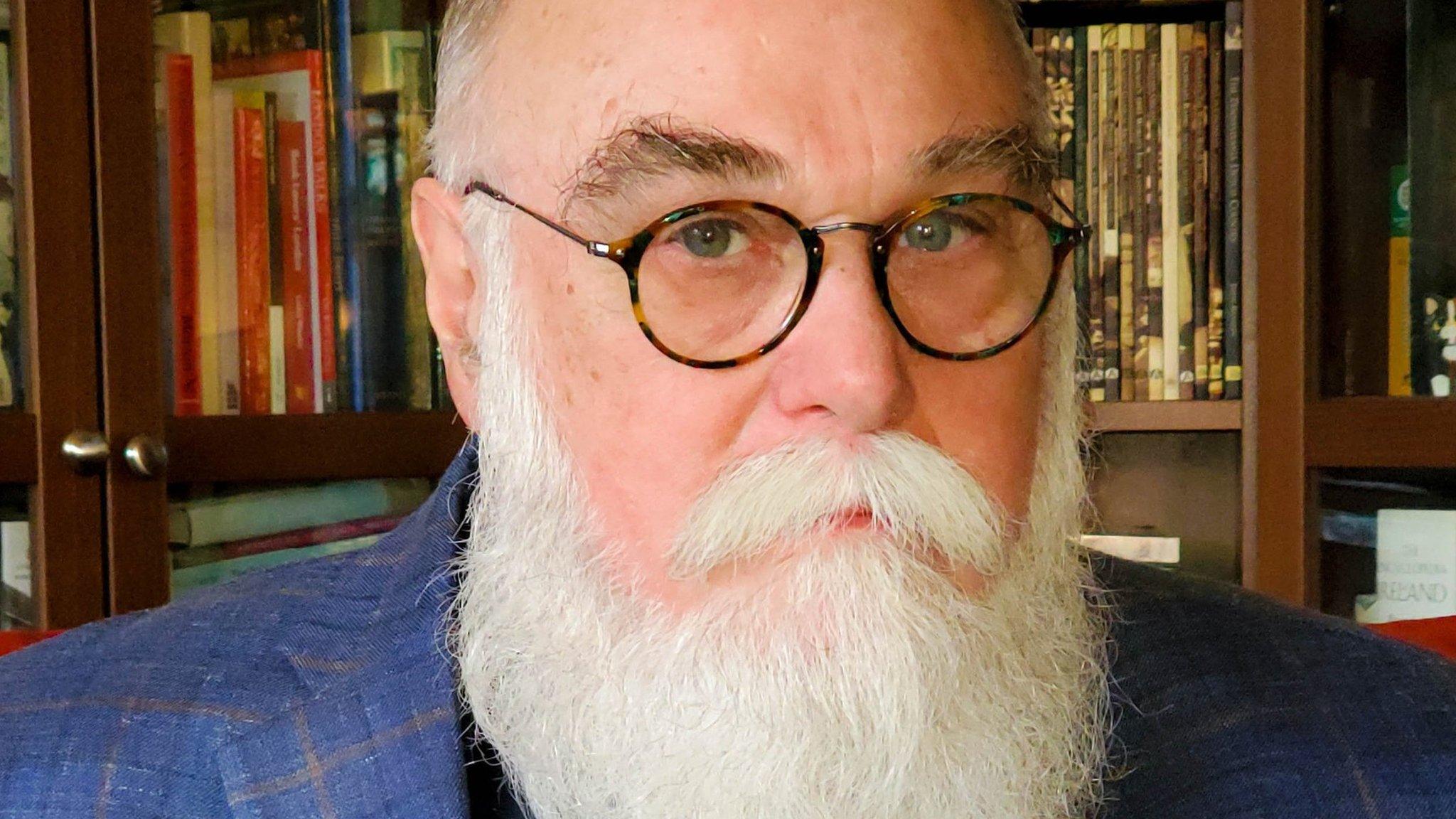

Mark Bryant, executive director of Gun Violence Archive

Mark Bryant counts shootings for a living.

It's an around-the-clock job in the US - where more than two people died from guns every hour last year.

He's been doing it for nearly a decade, serving as the executive director of the Gun Violence Archive, external, a tiny non-profit that attempts to track every incident of US gun violence in real time.

For Mr Bryant, years of counting the dead have come at a cost.

"When we first started this, I would see a child killed and I could remember her name. I could remember the age, what city she was in and the circumstances of that shooting. Now, I cannot do that," Mr Bryant says.

"It just doesn't stick anymore."

Mr Bryant spoke with BBC News earlier this month, the day after five people were killed in a mass shooting at a Kentucky bank, and two weeks after six people were killed in a mass shooting at a Tennessee elementary school.

During the interview, Mr Bryant's phone beeped with the notification of yet another mass shooting. This one was at a funeral home in Washington DC - 20 minutes after a service had ended for another man shot and killed in March, police later said.

There have been at least 170 mass shootings in the US in 2023 - defined by the Gun Violence Archive as four or more people shot, minus the gunman - in which at least 233 people died, including the shooters themselves.

It's a sign of how many such incidents there are in the US that this figure will likely already be out of date by the time this story is published.

But mass shootings are only a small blip on the radar compared to the everyday horror of the totality of gun violence incidents in the US.

As of 26 April, 13,386 people died in gun violence incidents this year. This includes the 20-year-old woman who was shot after entering the wrong driveway. Thousands more have been injured, like the 16-year-old boy who was shot after knocking on the wrong door.

Mr Bryant, a self-described data nerd, started the Gun Violence Archive in 2013, having spotted a "big gap" in the availability and accuracy of up-to-date statistics. He sought to do something about it.

"When we got this thing started we thought this was going to just be five years, but we just kept growing and kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger," Mr Bryant says.

So did American gun violence.

Nearly 6,000 more people died from guns in 2021 than in 2016, according to the Gun Violence Archive

Between 2016 and 2021, the number of deaths from gun violence increased by 6,000, or almost 40%; the number of teens killed or injured by guns was up 47%; the number of children killed or injured by guns, was up 60%.

Tracking these gruesome statistics has taken a toll on Mr Bryant, who says he sleeps about six hours a night, going to bed at 05:00 and waking up at 11:00.

"I've gained weight since I've started doing this job… I'm not taking as good care of myself as I should," he says.

"My wife came in the other day and literally I was asleep[at the computer]. I had my hand on the mouse and the other hand on the keyboard."

Mr Bryant keeps watch over the grim toll of US gun violence from his home in Kentucky. The organisation's other 24 contracted employees also work remotely and are spread across the country.

To provide what effectively amounts to a 24-hour ticker of gun violence data, Mr Bryant said he and his team go through 3,000 to 4,000 sources daily: law enforcement websites, local news, social media and blogs.

"It's not hard physically, it's hard mentally," he says. "I've gotten callous. Nothing surprises me anymore."

"If I got a beep right now that said there's a mass shooting with 42 people shot, I'd be like, OK, there's the rest of my day."

For some of his staff, however, it's not that easy.

"We've had other employees, other folks, one too many babies got killed and they just could not handle it anymore," Mr Bryant says. "I'm constantly hunting for new people."

Fatal mass shootings, like the one at a bank in Louisville this month, count for just a fraction of US gun violence deaths

One might think that being so acutely aware of the harm caused by guns - the number one cause of death for teens and children in the US - would make Mr Bryant anti-gun. It does not.

He fired his first gun when he was five years old; he learned to shoot from the dads of eastern Kentucky who would gather after church on Sundays and take aim at the rats running along the garbage dump.

"I own handguns, target pistols, revolvers," he says, most of them inherited.

"An uncle would die, and his wife would go 'here, take this'… so I ended up with this weird collection."

"I'm not against guns," Mr Bryant says. "Somebody has made the assumption that I'm doing this project that I must be against guns but lo and behold, I own guns."

"One thing I don't do, I don't have rifles. I don't hunt," he says. "I don't have an interest in an AR-15. I don't have an interest in assault weapons."

The more the American gun violence epidemic has grown, the more demand there has been for clearly sourced, reliable statistics.

And Mr Bryant's work shows no sign of slowing.

"I don't understand what makes people that way," Mr Bryant says. "There's a lot of anger and hate."

Watch: Why are these Americans turning in (some of) their guns?

The archive began as a project for the website Slate and formally launched with financial help from a businessman with an interest in enhancing transparency.

It has become a go-to source for BBC News and most major US media outlets, lawmakers and even the Supreme Court - those looking to make sense of American gun violence.

Although the FBI and Centers for Disease Control both collect similar data, their information generally isn't released until months - or years - after the fact. Comparatively, Mr Bryant said the archive adds most shootings to its website within roughly 72 hours.

"There's a level of irresponsibility in guns that needs to be solved so people don't die," he says. "I want to stop the violence."

The very act of assembling statistics on a fraught, politically and emotionally divisive topic like gun violence, however, has brought pressure and scrutiny.

"I sometimes tick off people on the gun violence prevention side and I certainly sometimes tick off people on the gun rights side, but my best day was when I published a piece of information and both of them were angry with me," he says.

"That told me I was doing my job correctly."

"We are statistics only. We literally just plot along numbers," Mr Bryant says. "Just keep on counting. That's what we do - just keep on counting."

Related topics

- Published21 April 2023

- Published8 August 2023

- Published15 April 2023

- Published17 December 2024