Their plane went down - how this WW2 Canada crew survived

- Published

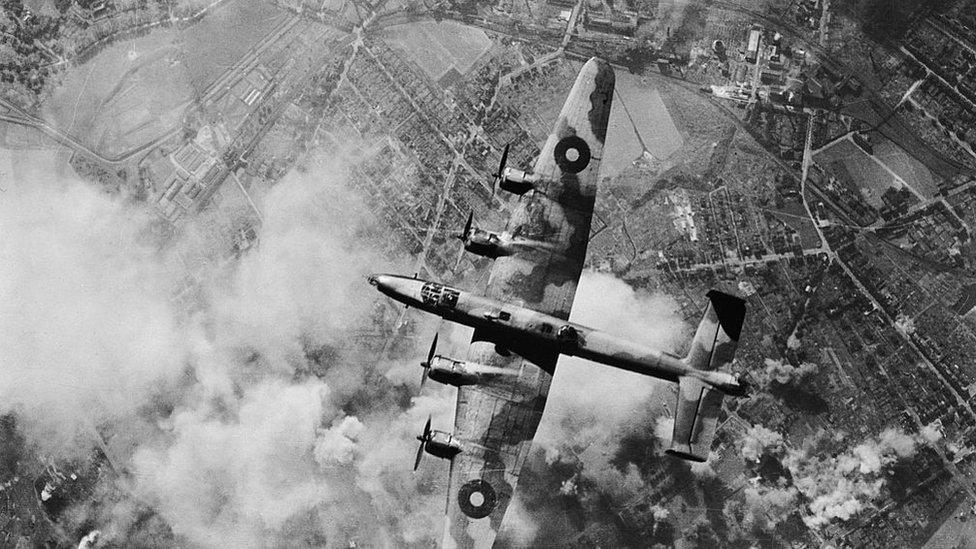

A Handley Page Halifax flies over the smoke-obscured target during a daylight raid on an oil refinery in the Ruhr

On 1 May, 1943 a plane carrying a mostly Canadian crew went down in the Netherlands. Eighty years on, the BBC is retelling the events of that fateful day - and their far reaching consequences - as part of our ongoing project "We Were There", which features British veterans telling their own stories for future generations.

For as long as Janet Reilley can remember, the first day of May has been one of remembrance for her family - of lives lost and saved in combat.

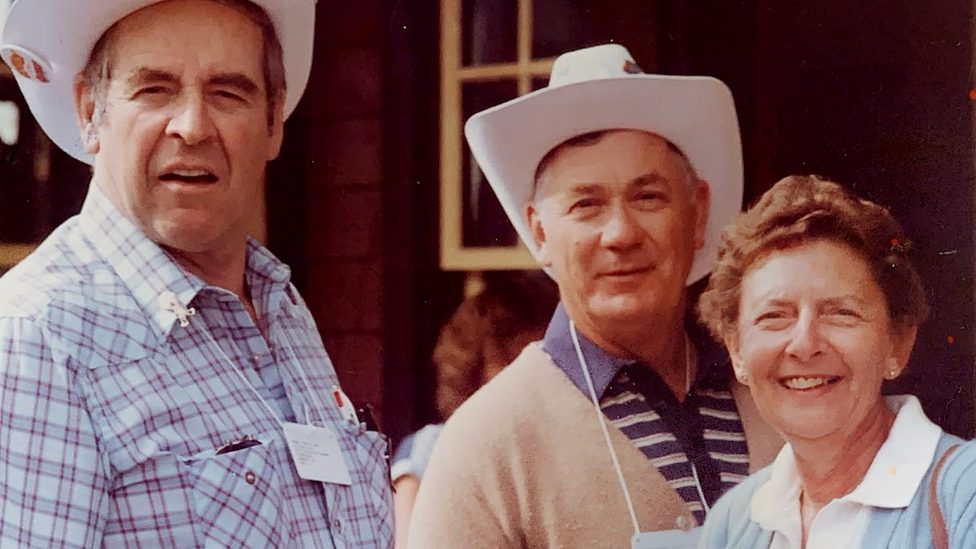

Her father "Mac" Reilley would pick up the phone to his friend "Buddy" MacCallum, to remember the events of 1943 that shaped their young lives - and their futures.

Few of "the greatest generation" who fought during World War Two remain to bear witness. Now, it's up to their descendants to keep their memory alive, so that others might understand the bravery, sacrifice and trauma of one of the 20th Century's defining conflicts.

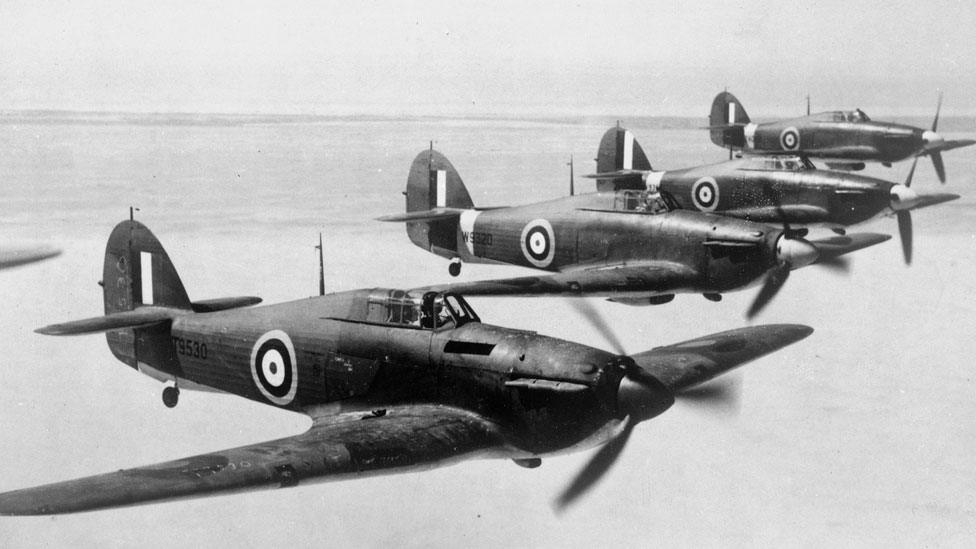

This particular story, of the crew of a Handley Page Halifax heavy bomber, is about how a small group of young Canadians flew in the skies over Europe during the Battle of the Ruhr. That plane was just one of more than 8,000 aircraft lost in action during Allied bombing operations.

Using their own recollections and those of their families, as well as records from the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, the BBC is retelling the story of how their plane went down, the drama of their capture and how some of them survived.

Mac Reilley (left), Buddy MacCallum and his wife Rose MacCallum at the 40th anniversary POW reunion in Calgary, 1985

The core of the crew - "Andy" Hardy, MacCallum and Reilley - first flew together in July 1942. By the spring of 1943, they were joined by tail gunner "Red" O'Neill, flight engineer Ken Collopy, and upper gunner, Norm Weiler, one of only two non-Canadians.

The other was my great uncle, Flight Lieutenant Herbert Philipson Atkinson, otherwise known as "Phil the Englishman". MacCallum, the wireless operator, believed they were lucky to have one of the best pilots in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

So high was the rate of loss in their squadron that they were considered both an "old" and "lucky" crew. The odds were against them - only about 15% of RCAF crews flying on the same type of aircraft survived a full tour in 1943, according to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada. , external

The fatal night

At 14:00 on 30 April 1943, alongside five other crews, they received a two-hour briefing of their operation for that night - Essen, described to them as one of the toughest targets in the Ruhr. Home to the Krupp steelworks, the city was vital to German military manufacturing.

Delayed due to fog over England, they set out at midnight. Shortly after 03:00, Atkinson gave the order to open the bomb doors over the "huge furnace, with thousands of searchlights and heavy flak guns blasting away" in the defence of Essen.

Suddenly Hardy, who was navigating, cried out, "I've been hit." An anti-aircraft shell had severed his right leg above the knee.

MacCallum tried in vain to save him, wrapping him in his bomber jacket to keep him warm and giving him morphine in his agonising final moments.

With their navigator dead, Atkinson told Reilley to release their bombs and then help him guide the aircraft clear of the target. Hardy's careful log and map table were unreadable with his blood, so Reilley plotted a course home to England from the flight plan and astral navigation.

Their luck runs out

"Fighter starboard!" shouted someone as the sound of cannon shells hitting the fuselage rang out. "Everywhere you looked was fire," recalled Weiler.

"The skipper dived and then pulled up, and the flames did die down a little, but flared up and spread over the wing as we dived to hold flying speed," recalled MacCallum. Atkinson's decision to dive stopped the aircraft from stalling and rolling over, giving his crew the chance to follow his instruction to bail out.

Reilley and O'Neill had bailed out before, the only survivors of a crash in October 1942.

That event is traced in the Canadian landscape at Mount Hudema in British Columbia, which Reilley had named in honour of the pilot. It is one of more than 950 locations in the territory with a name connected to World War Two.

The last to leave the plane was Callopy, with Atkinson remaining to fly it so his crew could safely bail out. He did not survive.

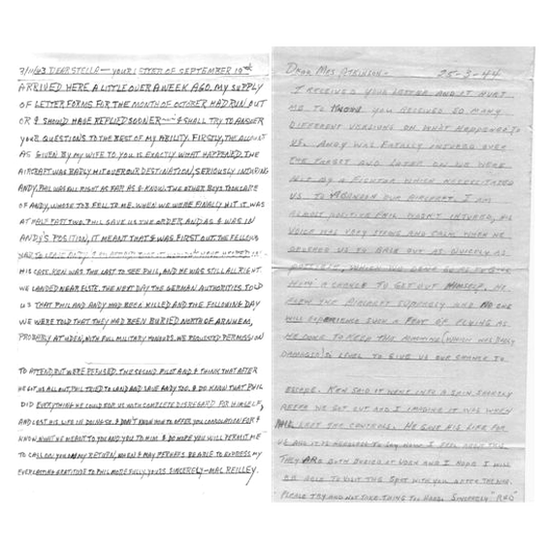

Atkinson with his wife Stella. All of the crew knew her from being invited to their home by their "skipper", or pilot

"He did everything he could for us with complete disregard for himself". Both Reilley and O'Neill wrote to Atkinson's wife from POW camps to tell her what had happened

But six members of the crew did - landing in fields and trees around Elst in the Netherlands, where they were captured as prisoners of war (POWs).

Surviving life in captivity

Years later, Weiler recalled how after landing in a field of cows, he had heard the bombers in the air returning home, and had felt "a sickly and lonely feeling" as he contemplated what fate awaited him.

They were swiftly separated and sent to camps across Nazi-controlled territory. Collopy and O'Neill to Northern Germany, MacCallum to occupied Lithuania, and Reilley, Nurse and Weiler to occupied Poland.

As an officer, Reilley went to Stalag Luft 3, where an elaborate escape attempt would go on to inspire the Hollywood film "The Great Escape".

That film dramatises the efforts to dig three tunnels from the prisoners' living quarters to the woods beyond the perimeter fence.

In real life, the plan was to let 200 RAF officers to escape through Germany using forged documents and civilian clothing, all created within the camp.

Only 76 officers made it out of the tunnel, and only three managed to not get caught. The Gestapo executed 50 in retribution.

Jim Glennie was an 18-year-old soldier when he faced the terrifying reality of the D-Day landings

Reilley, who was number 86 in line to escape, never made it into the tunnel he had helped build. Originally, he did not even know he was signing up for the escape plan - he thought he was joining a prison cricket league.

"It was my task to haul sand brought up from the tunnels to wherever it was being dispersed; as well I did a bit of security when my knee was really bad," Reilley would recall, having injured his knee and ankle when he landed in some trees after bailing out of the Halifax.

That knee would cause him more trouble, when he was forced to march, along with other Allied prisoners, through bitter winter conditions towards the end of the war. The Nazis wanted to use them as a human shield to limit the final onslaught of bombing raids on major cities.

They survived four months trekking aimlessly for hundreds of miles on foot, faced with the ever-present risk of death by starvation, exhaustion, exposure or summary execution. MacCallum, a Nova Scotian, maintained he had never experienced such a "bone-chilling" cold.

He narrowly avoided being killed by his own side when their bedraggled column was mistaken for a German unit by Allied aircraft. The scars on his heels from marching without socks would last a lifetime.

Only Collopy and O'Neill would be spared from marching.

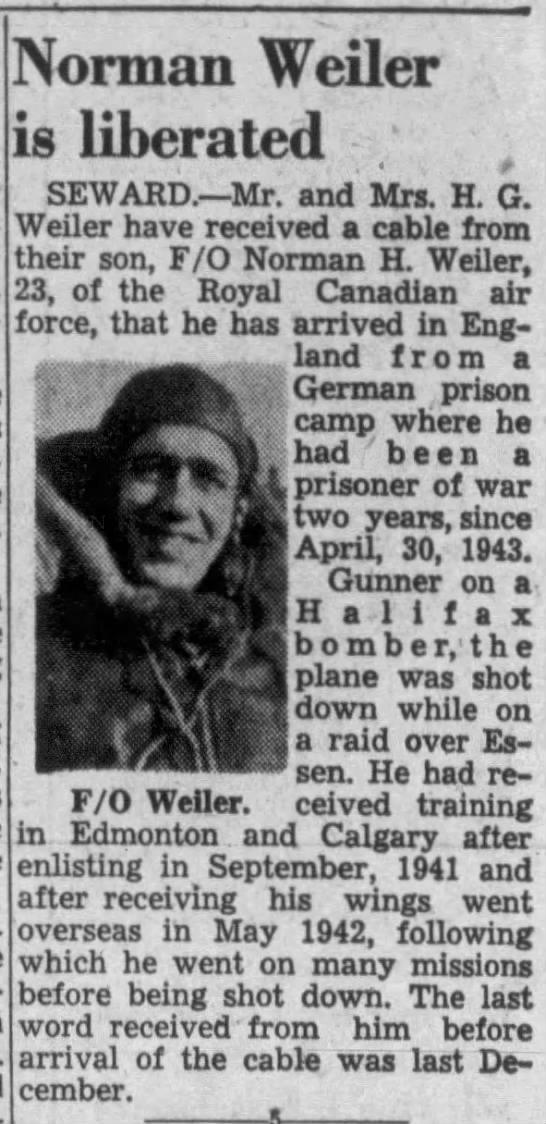

A clipping from the Lincoln Journal Star, reporting that Weiler had been liberated and made it back to England, 22 May 1945

Two years and a day after the crash, Reilley was liberated by the Cheshire Regiment near Lubeck, northern Germany, having lost 55lb (25kg) since the start of the war.

MacCallum was freed on the banks of the River Elbe, while Weiler was liberated near Munich.

Life after the war

The six who returned were all still in their 20s, young men who had left Canada to serve.

For MacCallum, making it home meant he would get to marry Rosemary. They had met before the war and had an understanding that if he came back alive, they would wed. They did so on 14 July 1945.

Rosemary and George MacCallum on their wedding day, 14 July 1945

Their entire courtship had been conducted by handwritten letters over the course of the war. "It blows my mind that somehow letters got between Grafton and Poland or Lithuania," says their eldest son Wayne.

They were expected to find jobs and carry on with life. So MacCallum, who'd gone to war at 18 straight from school, trained as an electrician and built a home for himself and his new family.

With help from his father-in-law to get work initially, Buddy and Rose would build a life in her home town of Grafton. She still lives there, not far from Wayne.

Collopy returned to work the family wheat farm on the edge of Frobisher, a village of 150 people in Saskatchewan.

Those who made it back alive would raise families, knowing that 17,000 men who volunteered for the RCAF would never get that opportunity.

During his RCAF service Red O'Neill (left) survived bailing out of three bombers, twice alongside Mac (right). After the war, he would go on to work for Canada's UN mission in New York

They carried with them not just physical but emotional injuries from their experiences.

Wayne would only discover that his father had endured nightmares for the rest of his life after his death in 2021. During his lifetime, his dad "kept it to himself, except when he talked to Mac".

Janet, Reilley's daughter, remembers how her dad gave up alcohol when she was three, having used it to cope with the continued memories of surviving the crash, imprisonment and the forced march. He was hospitalised twice in a psychiatric unit when his trauma became unbearable in the 1950s.

"Sometimes in the middle of the night when sleep will not come but vivid memories do I wonder if it was all worth it. And yet I have to be honest and say that in spite of it all I am glad that I saw fit to volunteer," Reilley said.

Today Janet Reilley, is hoping that she can keep alive the family bond forged in war with Wayne MacCallum. It has lasted 80 years so far, along with the abiding memories of what "the greatest generation" gave and lost for peace.

Related topics

- Published22 April 2023

- Published26 December 2022

- Published9 December 2022