Jack Teixeira: How are US security clearances handled?

- Published

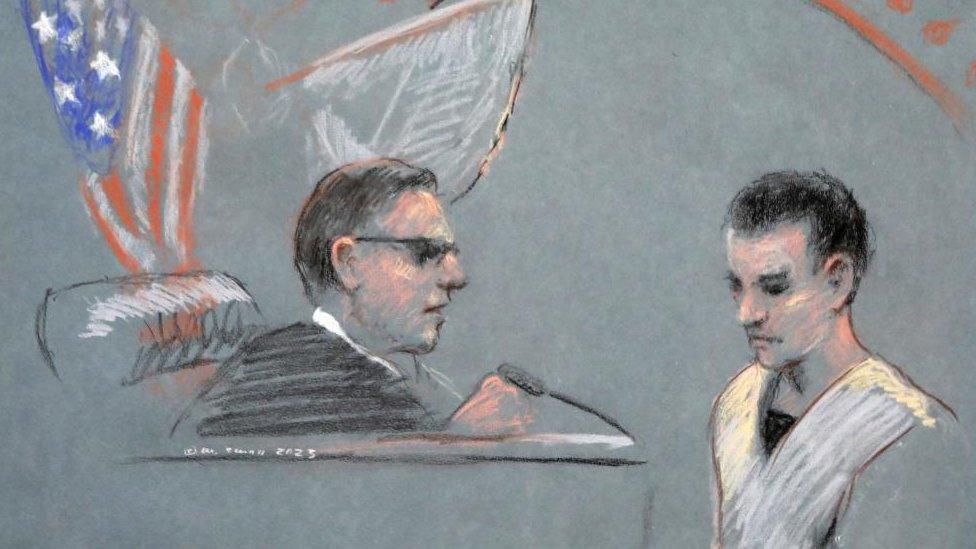

Jack Teixeira had a 'top secret' clearance for his work with an Air National Guard intelligence unit.

The young US airman accused of leaking Pentagon documents is alleged by prosecutors to have researched mass shootings, discussed violence and murder online, and kept a large arsenal of weapons.

Jack Teixeira, 21, had a top-secret security clearance which gave him access to sensitive and highly classified government documents. The case has prompted questions about the clearance process and the subsequent red flags that seem to have gone unnoticed after it was granted.

What gets checked for a security clearance

In 2018, a year before he joined the Massachusetts Air National Guard, Mr Teixeira was suspended from high school after being overheard making threats and discussing weapons.

The same year, he made an application for a firearms identification card which was denied over police concerns about his remarks.

Neither incident prevented him from passing the background checks needed to get security clearance for his job as an IT specialist in an intelligence unit.

In the US, security clearances are issued by a wide array of government agencies ranging from the CIA to the Department of Energy. The vast majority are issued by the defence department, according to ClearanceJobs.com, a job portal focused on government jobs that require clearances.

Most agencies have four main levels of security clearance: confidential, secret, top-secret, and "sensitive compartmented information", which has been called "above top secret", and can include material from intelligence sources.

The process of obtaining a security clearance begins with a suitability check to determine eligibility for the job, and applicants then have to fill in an exhaustive form. Standard Form 86, or SF86, includes personal data such as education and employment history, details of family and associates, and foreign travel and connections. It also asks about criminal history, military service, and financial issues.

Applicants then undergo police record and credit and employment checks. In some cases, they can be interviewed and agencies might look for personal references and even a lie detector test.

They usually need to supply information dating back about seven to 10 years, though that varies by agency. Mr Teixeira received his top secret clearance in 2021, three years after the high school incident.

If "red flags" are raised during an investigation, those individuals are given an opportunity to address those issues, says Steve Stransky, an adjunct law professor at Case Western Reserve University who previously served as senior counsel to the Department of Homeland Security's Intelligence Law Division.

"They have an opportunity to explain that and justify what occurred, as well as any mitigation measures they put in place and how they've evolved and changed in terms of their personality," he explained.

"Those are character judgements that the review process has to make on an individual basis, and those are hard decisions to make."

At a hearing to decide if he should be held in pre-trial detention, Mr Teixeira's lawyers said his suspension was "thoroughly investigated". They said he was allowed back to school after a psychiatric evaluation and that the incident was factored in when he was cleared for his job.

"The investigation was fully known and vetted by the Air National Guard prior to enlisting and also when he obtained his top-secret security clearance," the defence added.

Picking up online threats

Once granted, "top-secret" and "secret" security clearances are re-investigated every five years.

Court documents allege that Mr Teixeira made violent threats and researched mass shootings online in July 2022, well after he received his security clearance.

Watch: How damaging are 21-year-old Jack Teixeira's US intelligence leaks?

Publicly available social media accounts have formed part of the security clearance check process since 2016. But Michael Mulroy, a retired US Marine, CIA paramilitary officer and deputy assistant Secretary of Defense, says that a review of a serving individual's social media is only likely if their superiors have a reason to be alarmed.

"If somebody in [Mr Teixeira's unit] had come to their chain of command and said he's posting racist, violent or antisemitic stuff, I think they'd absolutely look at that and there would be disciplinary action," he told the BBC.

"But if nobody tells, I don't think that they would review everybody who simply has a clearance."

In 2019, the last year for which data is publicly available, nearly 1.3 million people had a "top secret" clearance, while a total of 4.2 million people were deemed eligible to access classified information.

Both Mr Stransky and Mr Mulroy also noted that the government's ability to monitor the social media of serving members of the intelligence community is limited by resources.

"I don't think they have the manpower," Mr Mulroy added. "We'd have to have an army of social media investigators."

The Air Force has suspended the commander of the 102nd Intelligence Support Squadron where Mr Teixeira worked, as well as an administrative commander, while it conducts an investigation.

Related topics

- Published27 April 2023

- Published15 April 2023

- Published14 April 2023