If Trump isn't a spy, why is he being charged under the Espionage Act?

- Published

In more than 100 years since its passage, few of the many cases brought under the US Espionage Act relate to what most people think of as espionage - individuals actually spying on behalf of a foreign nation.

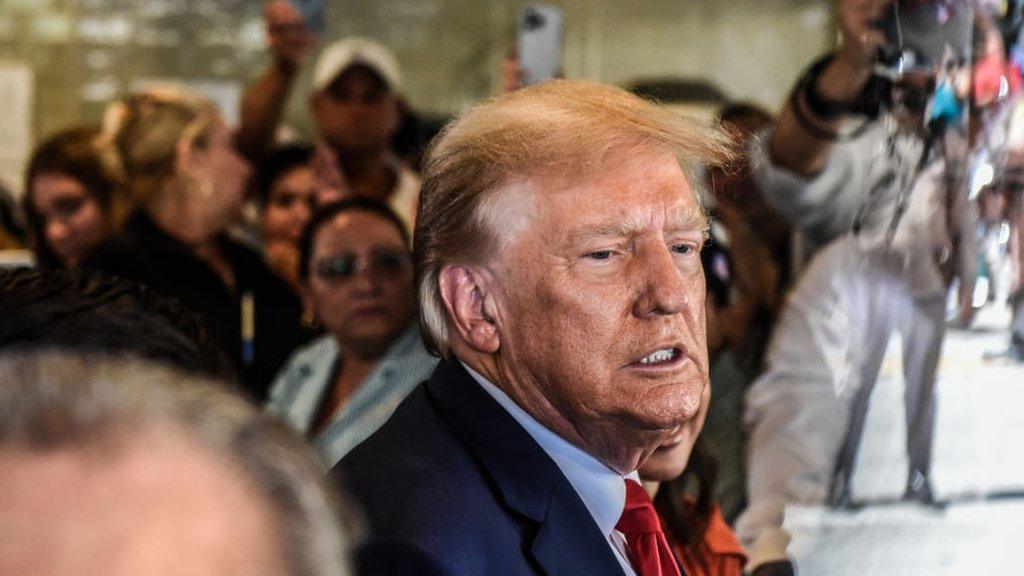

Since becoming the first ex-US president to face federal charges, including 31 Espionage Act violations, an emerging Republican defence of Donald Trump is to argue that he should not be charged under the act because he is not a foreign spy.

"You may hate his guts, but he is not a spy; he did not commit espionage," said South Carolina Republican Senator Lindsey Graham.

Florida Republican Senator Marco Rubio echoed that defence, saying Mr Trump did not conspire with America's enemies to harm national security.

"There's no allegation that he sold it to a foreign power or that it was trafficked to somebody else or that anybody got access to it," said Mr Rubio.

So why is the Espionage Act relevant?

The Espionage Act, external was passed by Congress in 1917, two months after the US entered World War One.

The law broadly criminalises the mishandling of government records "relating to the national defense" of the US. It is not strictly used to punish spies seeking to harm the US and in recent years has more often been used to punish whistle-blowers who expose government secrets to journalists.

Mr Trump, whose presidency ended on 20 January 2021, was not allowed to hold or possess classified documents as a private citizen, much less in an unauthorised place, after leaving office.

But prosecutors say he held on to hundreds of pages of sensitive information one year later at two of his resorts - even after he was asked repeatedly to hand everything over to the National Archives.

The part of the law referenced by the special counsel's indictment in Mr Trump's case - 18 US Code 793 (e) - does not say that the suspect must be working with another country to deliberately harm the US.

It says, in part, that it is a crime to have "unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over [information] … the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation," and to "wilfully" retain it while failing "to deliver it to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it."

Under the law, prosecutors will not be required to prove that Mr Trump knew that the information he possessed could harm national security interests, but rather that any reasonable person would understand the harm it could do.

They will instead focus on Mr Trump's efforts to "retain" the information, even after being given multiple opportunities to surrender it to authorities.

It also is not necessary under the law to prove that the documents were classified - only that they relate to US national security - or that they caused any actual damage to US interests.

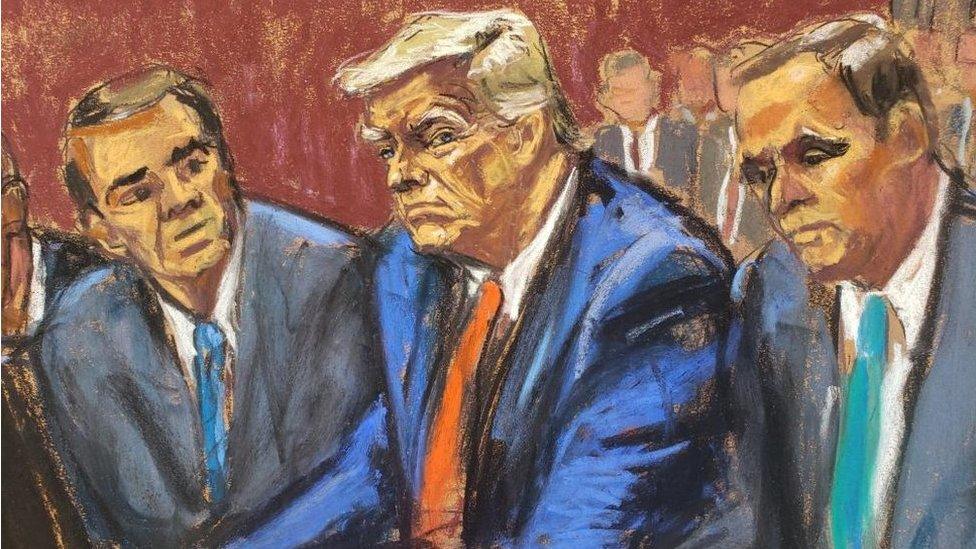

Watch: How Trump's indictment in Miami court unfolded - in 60 seconds

In the early days of the Espionage Act, it was used to prosecute political dissidents and peace activists who opposed forced military enlistment.

In the years since, it has been employed by the Justice Department against whistle-blowers like Daniel Ellsberg, whose Pentagon Papers leak shone a light on the Vietnam War, and Edward Snowden, a former intelligence worker who revealed a sweeping domestic surveillance programme.

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange has been charged with Espionage Act violations and is fighting extradition to the US. Intelligence workers Chelsea Manning and Reality Winner were also prosecuted under the act.

Penalties can be very harsh. In 1953 Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were put to death for violating the act by running a Soviet spy ring in New York.

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg

Other actual spies who were busted under the Espionage Act include Jonathan Pollard, who was caught spying for Israel, and CIA officer Aldrich Ames and FBI Agent Robert Hanssen who were both caught providing information to the Soviet Union.

According to the New York Times, about a dozen criminal prosecutions have been held since 2018 for illegal retention of national security documents under the Espionage Act.

Watch: The view from inside the Trump courtroom

- Published14 June 2023

- Published13 June 2023

- Published12 June 2023

- Published12 June 2023

- Published12 June 2023

- Published14 June 2023

- Published14 June 2023

- Published14 June 2023

- Published14 June 2023