How this man helped prevent a revenge murder

- Published

Tim Smith is one of hundreds of outreach workers on Chicago's west side

More police or more gun control? In debates about violence in America, the same solutions tend to get brought up over and over again. But Chicago is going all-in on a different strategy. Will it work?

Tim Smith knew trouble was brewing. Word on the street was that beef was developing between two rivals from different gangs in his neighbourhood on Chicago's west side.

It was his job to diffuse the tension, and he saw an opportunity in an approaching community event, complete with food, music and a bouncy castle.

"I met them earlier that day, and I told them they could come to talk," he recalls, "and I also said everyone has to come 'palms up'" - unarmed and non-violent.

The rivals - their territory separated by one of the city's main roads - came to chat on that neutral ground, and Tim says that they quickly found that they had family in common. The sharp anger that seemed important just a few hours before started to melt away.

There's no way to be entirely sure, but Tim, who works as a street outreach worker in one of the most violent communities in America, says the encounter prevented a shooting, which could have led to more bloodshed down the line.

"It was smooth after that," he says. "People were eating together. It wasn't like they were friendly and kicking it together, but there was respect."

These kinds of ground-level encounters are at the front line of a trend in crime prevention called community violence intervention (CVI).

At its core, CVI turns civilians with knowledge of the streets into crime-prevention workers, with the hope that they can do what police have tried and mostly failed to do for years in Chicago's toughest neighbourhoods: break the cycle of violence.

Highly concentrated murder

With more murders a year than New York City - despite having just a third of the population - Chicago saw violent crime increase over the past several decades even as it fell in other major US cities.

Things intensified in 2014, when 17-year-old Laquan McDonald was murdered by police. City officials blocked the release of footage of the shooting for more than a year, widening distrust between police and residents. Arrests went down and crime went up.

Then came the Covid pandemic and unrest following the murder of George Floyd. The year after, 2021, Chicago hit a high of nearly 800 murders - a rate not seen for nearly 30 years.

The violence is heavily concentrated in specific areas. Two-thirds of murders occur in just a handful of neighbourhoods, mostly on the city's west and south sides, according to the University of Chicago's Crime Lab.

By 2020, the murder rate in Austin and Garfield Park - poor, mostly African-American neighbourhoods on the city's west side - climbed to more than 1 in 1,000, making them some of the most dangerous urban neighbourhoods in the country.

People working to stop the violence talk not only of specific high-crime neighbourhoods but of even more concentrated hotspots - measuring just a few dozen blocks.

Boarded up buildings line the streets in Austin, one of Chicago's most dangerous neighbourhoods

Teny Gross founded the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago, a CVI programme, in 2015. It's located in a former school in Austin. Lockers and chalkboards still line the walls and the surrounding streets are dotted with boarded-up businesses and crumbling houses, legacies of decades of under-investment.

Mr Gross says police can't be expected to deal with the enormous scale of violent crime on their own. Civilian organisations, he says, can help quell problems before they blow up into murder, especially when combined with programmes delivering job training, psychological support and more.

"You cannot change an American city without CVI," he says.

Training academy

There are dozens of groups now working in the city, and they're becoming increasingly co-ordinated.

Earlier this year at the Metropolitan Peace Academy, a city-wide training institute for CVI workers, sessions included role-playing workshops, trauma lessons, job skills, community organising and more - underscoring the broad range of activities that fall under the CVI banner.

But the most dramatic part of outreach workers' jobs comes when they're asked to get involved when tensions are at their highest - right after a killing. One worker showed a text message from a system that sends alerts about shootings around the city.

"This is our call to action," he says.

In many cases the information is sketchy - for instance, a message from a hospital giving the age, sex and time of admission of a gunshot victim. Often there's no context, or even a name.

Workers then flip through their contacts, find out if there are plans for retaliation, and talk to gang members itching for revenge.

They don't pass information to the police. Any hint that they are working with cops would not only make people reluctant to talk, but also potentially put everyone involved in danger.

Trying to stop murders in real time is incredibly stressful, several outreach workers say, but also something they're familiar with. The vast majority of workers have been shooting victims, violent criminals, or both.

Tim Smith, the outreach worker on the west side, spent 13 years in prison for his involvement in a gang fight that left a man dead.

He credits older inmates for educating him about black history, and encouraging him to look for a future outside of prison and crime.

Now he's found a job where his past is an asset, rather than a liability. He's a natural communicator, and he knows how to relate to the neighbourhood "shorties" - young men getting caught up in gangs and violence.

"You have to meet people where they are," he says during a break in the training. "I know how to talk to them because I've been there."

Is it working?

CVI supporters point to evidence that it works, although the range of tactics and settings means it's unclear where and when it can really make a difference.

Research out of Northwestern University says one CVI programme stopped nearly 400 shootings over a recent five-year period. The study compared areas where one project was operating to similar neighbourhoods without an equivalent CVI project.

Andrew Papachristos, who led the research, says there are still some big unanswered questions, like how murder rates are impacted by the overall ebb and flow of crime rates. While murders appear to be down in certain neighbourhoods, car-jackings, muggings and crime on the city's public transport system are still stubbornly high.

"Often times these initiatives work, sometimes they don't," he says. "But we can't yet tell what causes them to work and what causes them not to work."

But CVI has one key public policy advantage beyond the crime numbers - it sidesteps America's divisive debates over policing and gun control, potentially making it more politically palatable.

US President Joe Biden has championed it. Last year the US Justice Department promised $100 million to CVI groups, external, on top of billions of Covid relief funds that can be used for such initiatives.

Private foundations and local governments have also given large sums.

But recent violence has shown how difficult progress can be.

Overall, murders are down slightly so far this year. A recent statement by Chicago Police specifically praised the role of workers who "spent time connecting with the city's young people".

On the other hand, when the city's new mayor, Brandon Johnson, promised $2.5 million in funding and 30 peacekeepers over the recent Memorial Day weekend, that effort failed. There were more than 50 shootings and 11 deaths, making it one of the bloodiest Memorial Day holidays in the city for years.

That leads to a major question: Will politicians and private institutions have the will - and the funds - to keep backing community programmes, even if crime rates increase again? Or will CVI join the long list of other crime-prevention trends

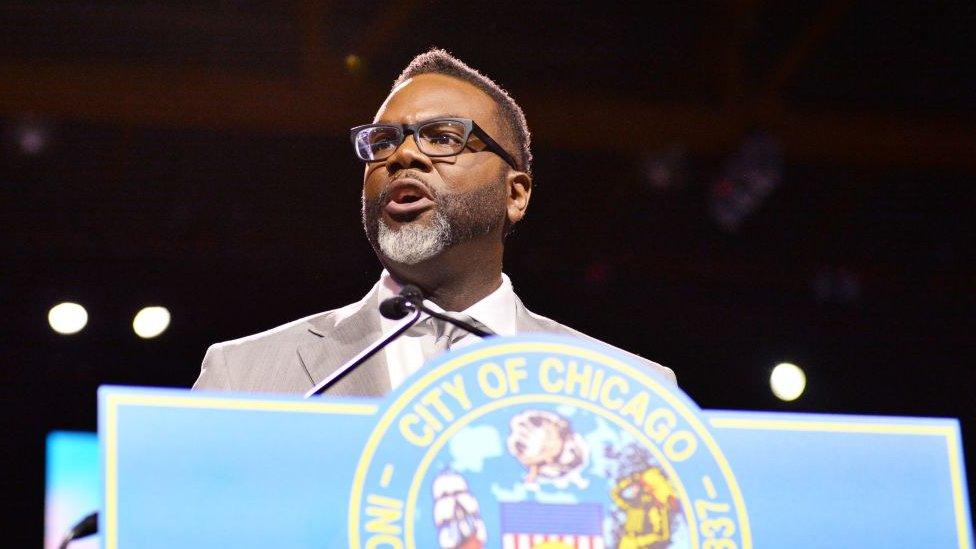

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson has pledged support for CVI programs

Just the start

For now, experts and outreach workers also have something that's been rare in recent years: a glimmer of hope. Tim Smith says he's trying to keep a shaky peace together in his neighbourhood.

"Youth feel a lot more comfortable coming to us," he says, before going out and committing violence. "We're getting the word out, letting them know they have a safe space and someone just to talk to."

But he's aware of the massive challenges that lie ahead, and says that the truce he hammered out earlier this year represent just the tip of his work.

"When I think of a true success story, I think of one of my participants getting a job," he says. "Getting people to put down their guns? That's just another day, where hopefully I stop someone from getting shot or going to jail."

Related topics

- Published24 October 2022

- Published17 December 2024

- Published5 April 2023