Cluster bombs: Unease grows over US sending cluster bombs to Ukraine

- Published

The remnants of a cluster bomb found in a field in Ukraine in April 2023

Several allies of the US have expressed unease at Washington's decision to supply Ukraine with cluster bombs.

On Friday, the US confirmed it was sending the controversial weapons to Ukraine, with President Joe Biden calling it a "very difficult decision".

In response, the UK, Canada, New Zealand and Spain all said they were opposed to the use of the weapons.

Cluster bombs have been banned by more than 100 countries because of the danger they pose to civilians.

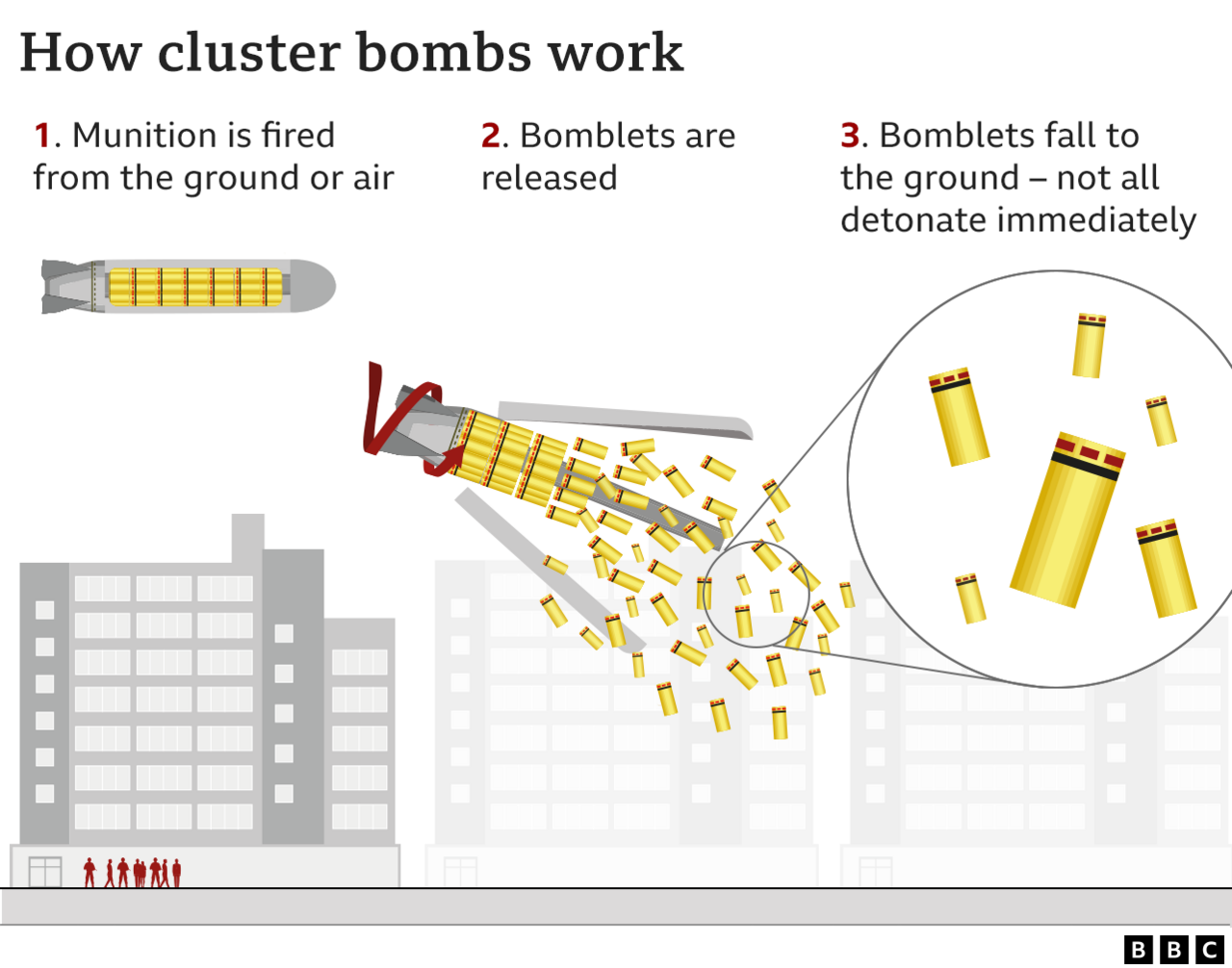

They typically release lots of smaller bomblets that can kill indiscriminately over a wide area.

The munitions have also caused controversy over their failure - or dud - rate. Unexploded bomblets can linger on the ground for years and then indiscriminately detonate.

Mr Biden told CNN in an interview on Friday that he had spoken to allies about the decision, which was part of a military aid package worth $800m (£626m).

The president said it had taken him "a while to be convinced to do it", but he had acted because "the Ukrainians are running out of ammunition".

The decision was quickly criticised by human rights groups, with Amnesty International saying cluster munitions pose "a grave threat to civilian lives, even long after the conflict has ended".

US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan told reporters the American cluster bombs being sent to Ukraine failed far less frequently than ones already being used by Russia in the conflict.

But on Saturday, some Western allies of the US refused to endorse its decision.

When asked about his position on the US decision, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak highlighted that the UK was one of 123 countries that had signed up to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which prohibits the production or use of the weapons and discourages their use.

His comments came ahead of a meeting with President Biden, who is due to arrive in the UK on Sunday before a Nato summit in Lithuania.

'Damage to innocent people'

The prime minister of New Zealand - one of the countries that pushed for the convention's creation - went further than Mr Sunak, according to comments published by local media.

Chris Hipkins said the weapons were "indiscriminate, they cause huge damage to innocent people, potentially, and they can have a long-lasting effect as well". The White House had been made aware of New Zealand's opposition to the use of cluster bombs in Ukraine, he said.

Spain's Defence Minister Margarita Robles told reporters her country had a "firm commitment" that certain weapons and bombs could not be sent to Ukraine.

"No to cluster bombs and yes to the legitimate defence of Ukraine, which we understand should not be carried out with cluster bombs," she said.

Watch: US military video shows how cluster munitions explode

The Canadian government said it was particularly concerned about the potential impact of the bombs - which sometimes lie undetonated for many years - on children.

Canada also said it was against the use of the cluster bombs and remained fully compliant with the Convention on Cluster Munitions. "We take seriously our obligation under the convention to encourage its universal adoption," it said in a statement.

The US, Ukraine and Russia have not signed up to the convention, while both Moscow and Kyiv have used cluster bombs during the war.

Meanwhile, Germany, a signatory of the treaty, said that while it would not provide such weapons to Ukraine, it understood the American position.

"We're certain that our US friends didn't take the decision about supplying such ammunition lightly," German government spokesman Steffen Hebestreit told reporters in Berlin.

Ukraine's defence minister has given assurances the cluster bombs would only be used to break through enemy defence lines, and not in urban areas.

Mr Biden's move will bypass US law prohibiting the production, use or transfer of cluster munitions with a failure rate of more than 1%.

Mr Sullivan, the US national security advisers, told reporters the US cluster bombs have a dud rate of less than 2.5%, while Russia's have a dud rate of between 30-40%, he said.

The US Cluster Munition Coalition, which is part of an international civil society campaign working to eradicate the weapons, said they would cause "greater suffering, today and for decades to come".

The UN human rights office has also been critical, with a representative saying "the use of such munitions should stop immediately and not be used in any place".

A spokesperson for Russia's defence ministry described the move as an "act of desperation" and "evidence of impotence in the face of the failure of the much-publicised Ukrainian 'counter-offensive'".

Russia's foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova also said Ukraine's assurances it would use the cluster munitions responsibly were "not worth anything".

Russian President Vladimir Putin has previously accused the US and its allies of fighting an expanding proxy war in Ukraine.

Ukraine's counter-offensive, which began last month, is grinding on in the eastern Donetsk and south-eastern Zaporizhzhia regions.

Last week, Ukraine's military commander-in-chief Valery Zaluzhny said the campaign had been hampered by a lack of adequate firepower. He expressed frustration with the slow deliveries of weapons promised by the West.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky thanked the US president for "a timely, broad and much-needed" military aid package.

One by one, America's Nato allies have been lining up to distance themselves from its decision to supply Ukraine with controversial cluster bombs.

Britain, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak made clear, is a signatory to the 2008 convention that prohibits their production and use - and discourages their use by others.

Canada went further, with a government statement saying it was committed to putting an end to the effects of cluster munitions have on civilians, particularly children.

Spain said these weapons should not be sent to Ukraine, while Germany said it was also against the decision, although it understood the reasoning behind it.

Even Russia condemned it, despite having made extensive use of cluster munitions itself against Ukraine, saying it would litter the land for generations.

But Gen Sir Richard Shirreff, a former deputy commander of Nato in Europe, defended the decision, saying their deployment should make it easier for Ukraine to break through Russian lines.

If the West had provided more arms sooner, he said, then there would not have been a need to provide this weapon now.

- Published12 June 2022

- Published10 July 2023

- Published8 July 2023