When a 'fire hurricane' hit, Maui's warning sirens never sounded

- Published

Smoke billows as wildfires destroy a large part of the historic town of Lahaina

Lahaina, once Hawaii's royal capital, is now a crematorium.

"We pick up remains and they fall apart," said Maui County police chief John Pelletier on Saturday, four days after a massive wildfire tore downhill through dry brush and grass and engulfed the island's western edge.

Close to 100 deaths have been confirmed, making the Lahaina wildfires the deadliest in the US in more than a century.

But just 3% of Lahaina's charred ruins have been searched so far, stoking fears that the death toll will continue its sharp climb.

"None of us really know the size of it yet," chief Pelletier warned, growing visibly emotional.

Dozens of survivors shared their stories of escape and loss with the BBC, helping to piece together a more complete picture of the tragedy that unfolded on Tuesday, when fires moving at a mile per minute consumed the town.

One thing seemed to unite their accounts: residents say they had no official warning before they fled for their lives, raising painful questions about the effectiveness of the emergency response and whether more people could have been saved.

Warning: This story contains details that some readers may find distressing

On Tuesday morning, Lahaina residents woke up to find their power was out. Phones hadn't charged, alarm clocks stayed quiet and air conditioners shut down.

For Les Munn, a 42-year-old resident, the outage announced itself in a dropped call to the country's east coast. He had woken up at 4:00am that day to accommodate the six-hour time difference. Mid-conversation, the connection was cut.

But the outage alone wasn't especially concerning, Munn said.

"I just thought it was going to be another blackout," he said, noting the trade winds that frequently hammer the coast.

Munn, like most others, assumed this outage was linked to nearby Hurricane Dora, which authorities had warned could bring gusts of up to 65mph (105kph) to Maui.

And at that time, the local fires apparently fuelled by Dora's winds seemed insignificant.

Watch: Extensive devastation left by Maui wildfires

By 9:55am, officials had declared the Lahaina brush fire "100% contained", external. Residents were given no indication it would flare up again.

Richard Tenison, a homeless Lahaina resident, woke up to the rushing winds. Standing up near the door of a pharmacy where he had set up for the night, he watched as his bedding was carried by the wind into the harbour.

The weather was building, said Lynn Robison, who lived in the heart of the historic town. By 8am she got her first whiff of smoke, an odour that would build throughout the day. But at that point concerns were muted. Hawaii was used to storms.

By around 3:00pm, things began to turn.

Les Munn fled his home with only the clothes on his back

Les Munn went outside to take out the trash. He chatted with his neighbours about the "strange wind", the gusts growing so fast and so loud they could barely hear each other speak.

They speculated, incorrectly, that the dust and ash in the air was due to construction. The group separated, peeling off into their separate units in the apartment block.

Suddenly, the building's smoke alarms began ringing. Residents emptied out of their apartments. Outside, embers had begun igniting the brush around them.

"At that point everybody started to panic," Munn said.

Munn ran back inside and tried to grab his wallet, but the heat and smoke forced him to flee with nothing but the clothes on his back. Everything went black. Choking on smoke, he fled to the only thing he could see, the blue lights of a police car, and dove into its back seat.

Munn hadn't heard a siren alerting him to the fire, and he hadn't received official notice to evacuate. Of the more than two dozen Lahaina evacuees who spoke to the BBC, no one did.

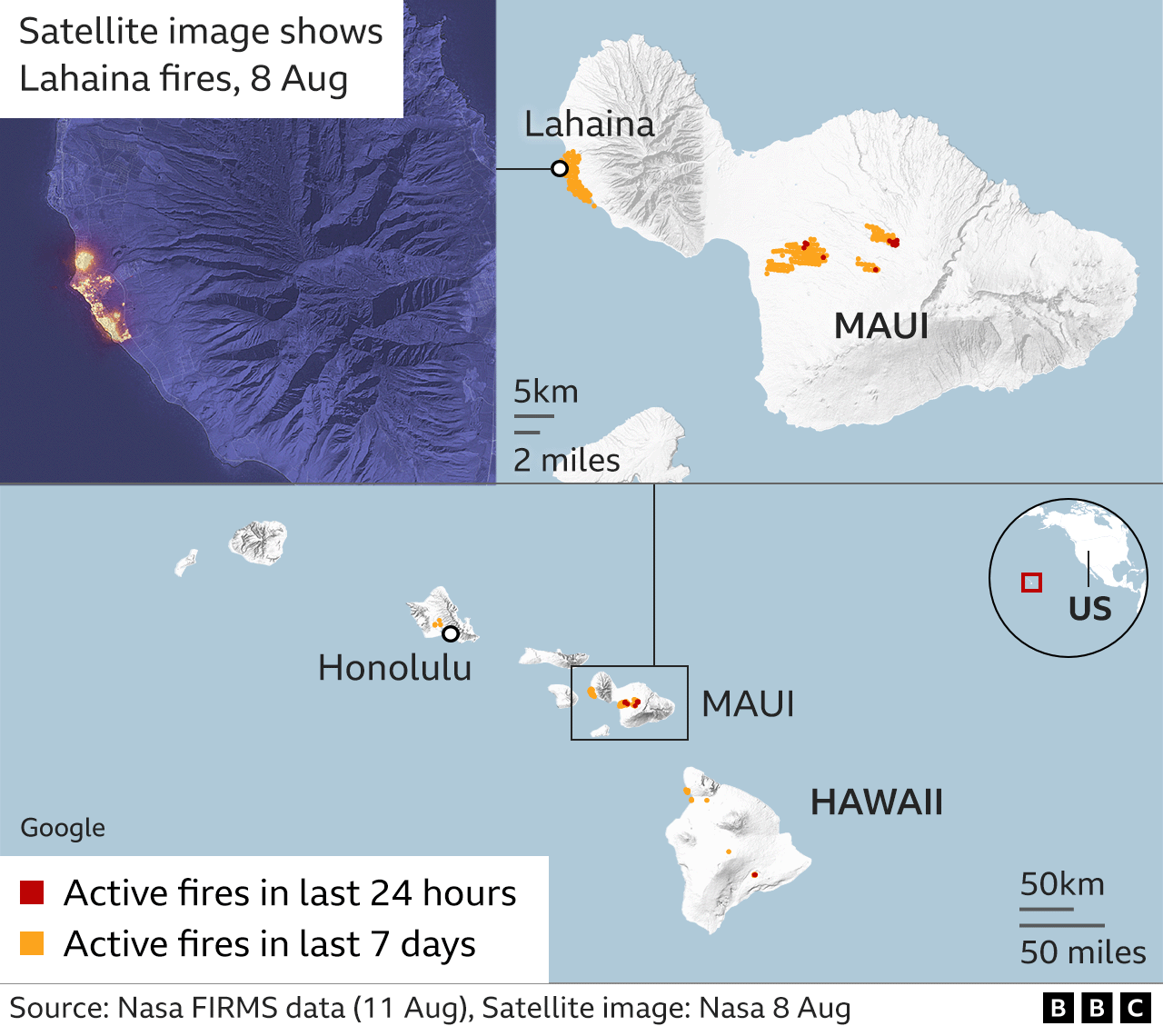

On Maui, the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, there are 80 outdoor sirens - tested monthly - intended to warn residents of tsunamis and other natural disasters.

But those early warning sirens had failed to sound, officials have confirmed, a failure now under investigation by Hawaii's attorney general. Some residents told other media outlets they received alerts to their mobile phones early on Tuesday, but the blackout across Maui's west may have limited their reach.

And in the absence of a wide-scale warning, residents described a frantic rush to escape a fire that seemed to appear from nowhere.

Some people - both officials and residents - have said the blaze may simply have moved too quickly for any formal response.

"It was a very fast-moving fire, it was a low to the ground fire," said Lori Moore-Merrell of the US Fire Administration on Saturday from Maui. "It outpaced anything that firefighters could have done in the early hours."

"The firefighters need to be commended for their actions," she added. The governor has also noted most resources on Tuesday had been focused on tackling other wildfires on the island.

A firefighter fights flare-ups in Kula, about 58km from Lahaina

Taken together, the accounts from Lahaina residents told of a seemingly instantaneous transformation from a sunny beach town into a site of near-total devastation. Dense black smoke descended as the fire barrelled toward the water, turning day into night.

The smoke was so thick and so dark residents could not see more than a few feet in front of them, nothing but bright red embers blowing through the air, burning their skin and everything around them.

"You couldn't see through it, people were crashing into each other trying to drive out," said Richard Tenison.

More than 2,200 buildings were razed, the houses, shops and churches that lined Lahaina's streets reduced to molten metal and ash.

Tenison watched as a friend's large home was incinerated. "His house went up in 10 minutes. Two-storey house, eight bedrooms… poof," he said. "It just levelled the whole town."

As he ran to safety in the town's Safeway grocery store, Tenison saw three bodies. "People were already dead," he said.

For Tee Dang, a tourist from Kansas, the first clue that her vacation had taken a deadly turn came in the form of an Airbnb host barrelling past her door and telling her family to run.

As the fire intensified, Dang sat in traffic on Front Street with her husband and three children. "It was only 3:30pm or 4:00pm and everything was pitch black," she said. "Everywhere was exploding."

When the cars on the road around them began to catch fire too, Dang and her husband grabbed their children and ran for safety in the ocean where they remained for almost four hours.

The injured family was rescued by a firefighter, who pulled around 20 people from the Lahaina harbour and told them to run towards the town's sport's complex.

Covered in burns and cuts, it was then that the family would receive their first official order to leave. Of the survivors who spoke to the BBC, many said the same, that the only formal notice from authorities came after they had already begun their escape.

At 4:29pm, Maui's emergency management agency had publicly announced perhaps its first evacuation order, external, writing on X (formerly known as Twitter) that residents of Kelawea Mauka, a neighbourhood on the edge of Lahaina, needed to leave.

But the notice was overtaken by conditions on the ground. By then, photos and video footage of the town show streets mauled by the inferno.

Steve Strode, one of Les Munn's neighbours, was first told to leave town after he had cycled through flames as tall as 10ft, reaching the relative safety of the Safeway grocery store. After a decade in Lahaina, hearing the blaring alarm tested each month, he did not understand why that same system did not push him to leave earlier.

Along with Strode and Tenison, several more people would arrive at the supermarket, huddling inside the building's metal structure before police came and told them to evacuate for their own safety.

For many, that evacuation was improvised, an ad hoc effort by both authorities and locals.

Residents like Lynette "Pinky" Johnson loaded their cars with as many as could fit, before driving eastward along the Honoapiilani Highway - the only viable route to safety - as flames lapped at their wheels.

"We saw the flames coming. We smelled the smoke. All of a sudden boom boom!" she said. "It was the sound of tyres and cars exploding."

By Sunday, Pinky remained at an emergency shelter at the Maui War Memorial Stadium, a cavernous, echoing gymnasium now filled with rows upon rows of cots and air mattresses, the new home for hundreds of Lahaina's displaced.

A fleet of volunteers have joined medical workers, physiotherapists, counsellors and translators to assist the thousands of displaced residents. Outside the gym, a large pink poster board advertised a designated missing persons tent where Maui residents can add the list of the missing - estimated to be up to 1,000.

Identification of the dead will not come quickly. Five days after the blaze, just two of the deceased have been named, easily outpaced by the growing list of fatalities.

"When we find our family and friends, the remains we're finding are from a fire that melted metal," police chief John Pelletier said. "You have to do rapid DNA testing to identify them. Every one of them [the deceased] are John and Jane Doe."

Sniffer dogs trained to detect bodies have been deployed to search for more victims under the rubble, their barks echoing through the devastated streets, now likened to a warzone.

In the absence of official identifications, most are learning of their dead neighbours and loved ones through Maui's so-called "coconut wire", the small island's robust whisper network.

And many who spoke to the BBC are convinced the number of dead will climb significantly in the coming weeks as authorities continue their painstaking search.

On Friday, Hawaii Governor Josh Green said the state's attorney general would be leading an investigation into Maui's emergency response policies. But he has mostly defended his government's response, blaming high winds and drought conditions.

"That fire travelled one mile every minute, resulting in this tragedy," he said in a statement on Sunday. "A fire hurricane, something new to us in this age of global warming, was the ultimate reason that so many people perished."

Still, many evacuees said they felt they were abandoned. In the days since they escaped, the guilt they carry for those left behind in Lahaina has mixed with growing anger at authorities who they claim could have acted earlier.

Liz Germansky, who lost her Lahaina home in the fire, said she blamed both the county and state government for the climbing death toll.

"Whether it be the prevention of it, or the notifications, they could not have done less," she said.

Germansky is now suing the government for gross negligence, property damage and emotional trauma.

Her home, she said, is now a crime scene. "It was murder".

Liz Germansky's levelled home

What questions do you have about the wildfires in Hawaii? You can send your questions to yourquestions@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

.

Related topics

- Published16 August 2023

- Published14 August 2023

- Published14 August 2023

- Published11 August 2023

- Published10 August 2023

- Published14 August 2023