Five players who will decide if US government shuts down

- Published

Watch: How does a government shutdown impact the US?

After a six-week hiatus, punctuated by an acrimonious leadership battle among Republicans in the House of Representatives, the US government is again facing a shutdown if Congress does not act.

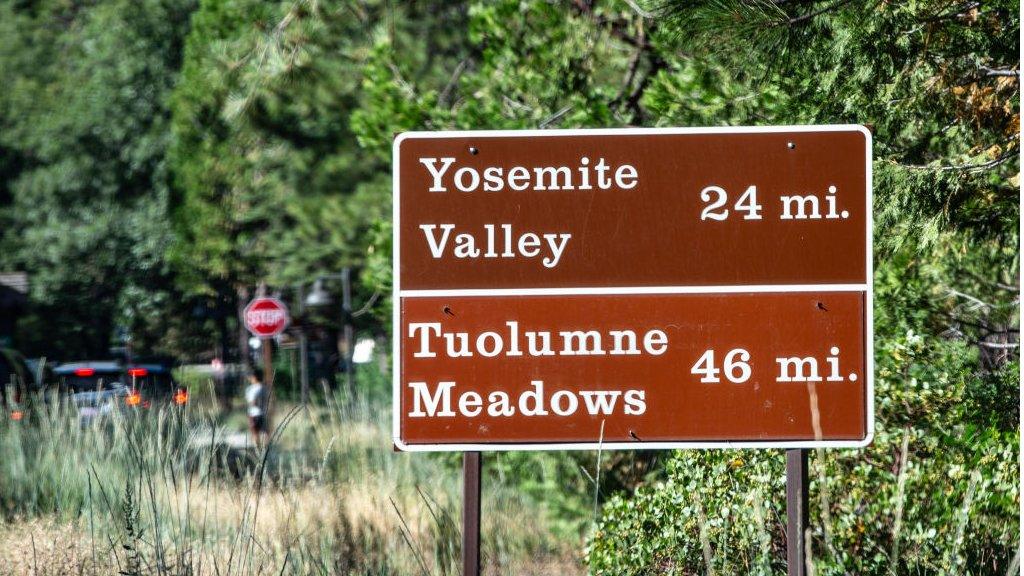

The prospect of shuttering national parks and sending federal workers and contractors home without pay has become a now-familiar drama, although this time around there are a few unusual twists.

Here's a look at the key players in the shutdown showdown, what they want and what it might take for the current political crisis to be resolved.

First test for new House leader Mike Johnson

The deal that averted the last government shutdown, a temporary funding measure that set this Friday as the new funding deadline, also cost Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy his job. A right-wing rebellion ousted the California Republican from the speakership and, after a multi-week struggle, delivered the gavel to Mike Johnson.

The Louisiana representative has only been in Congress since 2017 and has never before held a leadership position in the party. Now he faces a similar bind to his predecessor. He needs his chamber to pass new spending bills to allow the government to function for the coming fiscal year. To do so, he either needs nearly unanimous Republican support in the narrowly divided House of Representatives or he will have to work with Democrats to craft a bipartisan compromise.

If he does the latter, however, the right-wing members of the House may once again rebel. If he does the former, he will ultimately have to negotiate with Senate Democrats in order to find a compromise that the entire Congress can then approve. And pretty much any compromise will anger those right-wing members.

His plan is to offer a two-part government spending package. He would extend funding for veterans programmes, transportation, housing, agriculture and energy to 19 January. The second legislative piece would fund the rest of government operations, including defence, the State Department and homeland security, until 2 February.

The proposal is an attempt to win support of hard-line Republicans who don't want one big spending bill while wooing Democrats by keeping funding levels at those set by Democrats last year.

Right-wing Republicans threatened to block the measure before it even reached a vote, but Mr Johnson sidestepped their opposition with a procedural manoeuvre that will, ultimately, require Democratic support to pull off.

He has decided to risk angering his right wing in a bid to keep the government open - for now.

Remind me why the new speaker wanted this job again?

The hardliners - Chip Roy and the Freedom Caucus

House Republican hard-liners, fresh off ousting Mr McCarthy, are back to cause more discomfort for the party's leadership.

The right-wingers, most of whom belong to the conservative group called the Freedom Caucus, blocked consideration of a multiple spending bills over the past six months, including several in the past two weeks.

They've demanded that the House instead consider each of the major spending bills - on things like foreign aid, education, farming and transportation - individually and with their conservative priorities included.

At the heart of their objections is the view that the government spends too much. If a shutdown is the price for achieving their goals, they accept that. Some, who view much of what the federal government does as superfluous or even harmful, may even relish it.

"Calling yourself the party of 'limited government' means stopping AND CUTTING the explosive growth of the federal government fuelled by record debt," writes Texas Congressman Chip Roy, a prominent member of the Freedom Caucus. "The status quo is a fiscal death spiral."

Mr Roy, along with six other House Republicans, have already come out against Mr Johnson's two-part funding proposal - easily more than the four that would be required to sink the legislation if Democrats are unified in their opposition.

For the moment, however, their opposition to Mr Johnson's plan hasn't morphed into opposition to Mr Johnson himself. They seem willing to give him a bit more time to prove he can deliver the right-wing results they desire.

The president - Joe Biden and the Democrats

Speaking of the Democrats, their position on the government shutdown is fairly simple: This is a Republican problem, and Republicans have to solve it.

They are warily eying Mr Johnson's two-part proposal without tipping their hand on how they will ultimately vote.

On one hand, the resolutions are "clean", in that they keep funding at current levels and do not include any conservative items that they would consider deal-breakers.

On the other, the plan would tee up multiple shutdown dramas in the new year.

While some Democrats in Congress have been open to Mr Johnson's idea, the Biden White House initially expressed full-throated opposition.

"This proposal is just a recipe for more Republican chaos and more shutdowns - full stop," White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre wrote in a statement released Saturday. "House Republicans are wasting precious time with an unserious proposal that has been panned by members of both parties."

The White House has since backed away from such uncompromising rhetoric, as more congressional Democrats warm to the idea.

While Mr Johnson's plan does nothing to advance Democratic priorities, such as sending aid to Ukraine and Israel and re-authorising some programmes for the poor, they don't want to be viewed as responsible for triggering an end-of-year shutdown, either.

Mitch McConnell and the Senate

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell has been in politics for a long time. He's seen shutdowns come and go, and has seen his Republican Party bear the brunt of the political blame when they happen.

It's not surprising, then, that the Kentucky senator has played the Cassandra in this particular drama, warning his fellow Republicans of the danger that lies ahead.

"Government shutdowns are bad news," he said prior to the September shutdown showdown. "It's an actively harmful proposition. And instead of producing any meaningful policy outcomes, it would actually take the important progress being made on a number of key issues and drag it backward.

While House Republicans spin their wheels, Mr McConnell and his Democratic counterpart, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, to craft a temporary spending bill to avert a shutdown. The wily veteran has more than a few legislative victories under his belt - and may be the one politician most responsible for the current conservative makeup of the US Supreme Court.

If the House ultimately kicks the shutdown can into the new year, a bipartisan majority in the Senate is likely to agree with little drama.

Donald Trump

The former president casts a shadow over much of Republican politics, and the ongoing shutdown debate has been no exception.

In the past few weeks, Mr Trump has held his tongue, seemingly more focused on his New York civil trial and lashing out at what he called the "thugs" and "vermin" among the political left.

During the September shutdown drama, however, he urged the party to hold its ground and lambasted Mr McConnell as the "weakest, dumbest and most conflicted 'leader' in US Senate history".

"Unless you get everything, shut it down!" he wrote. He added that the president is always blamed for the lapse in government funding - although that has not typically proven to be true. If Mr Biden garners even part of the blame, however, that only helps Mr Trump in his quest to win back the White House.

At the very least, it seems to be a gamble he is willing to take. If the system is broken, he may figure, the public might be more willing to give him another shot to come back to Washington and fix things.

Related topics

- Published1 October 2021

- Published30 September 2023