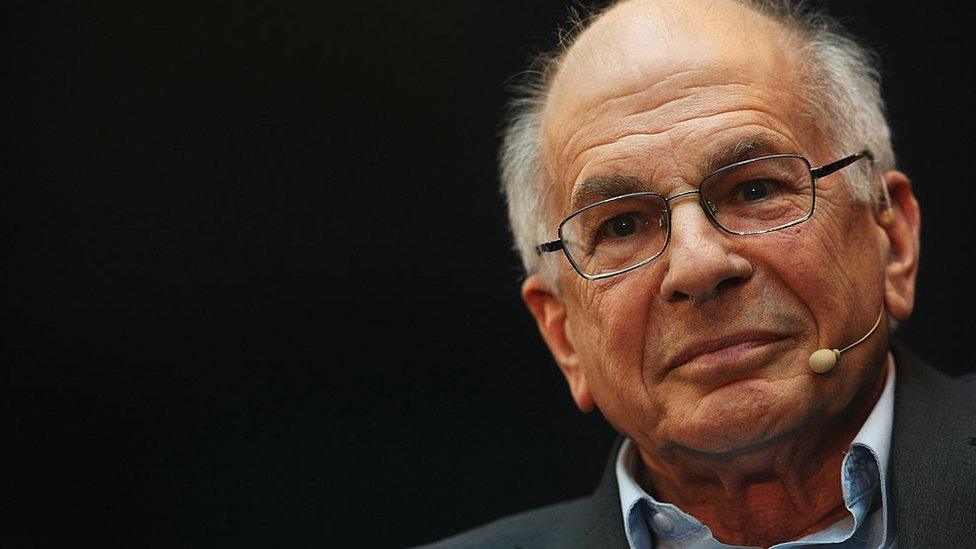

Daniel Kahneman: Nobel prize-winning behavioural economist dies

- Published

Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman has died, aged 90.

He became synonymous with behavioural economics, even though he never took a course of economics.

Kahneman wrote the best-selling book Thinking, Fast and Slow. It debunked the notion that people are rational beings who act out of self-interest - they act based on instinct, he argued.

His death was announced by Princeton University where he had been working since 1993.

"Danny was a giant in the field, a Princeton star, a brilliant man, and a great colleague and friend," said prof Eldar Shafir.

"Many areas in the social sciences simply have not been the same since he arrived on the scene. He will be greatly missed."

Kahneman was born in Tel Aviv, Israel, in 1934, and spent much of his early years in Nazi-occupied France, where his father worked as chief of research in a chemicals factory.

The family moved to what was then British-ruled Palestine in 1948, just before the creation of the state of Israel.

Kahneman graduated from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1954, and went to the US four years later to begin a doctorate in psychology at the University of California Berkeley.

Kahneman returned to Jerusalem in 1961 to begin his academic career as a psychology lecturer, where he met Amos Tversky - a cognitive psychologist with whom he did much of his most fundamental work.

He would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences in 2002

His work with Tversky formed the basis of the best-selling book Thinking, Fast and Slow, published in 2011.

The book explained the psychology of decision-making. It outlines two systems that drive the way humans think and make choices - the fast, intuitive, and emotional - and the slower, more deliberative, and more logical.

The book argued that most of the time, our fast, intuitive mind is in control, and takes charge of the decisions we make each day - rather than the deliberative, logical part of our minds - and this is where mistakes can creep in.

- Published24 February 2014

- Published25 July 2012