Suicide is on the rise for young Americans, with no clear answers

- Published

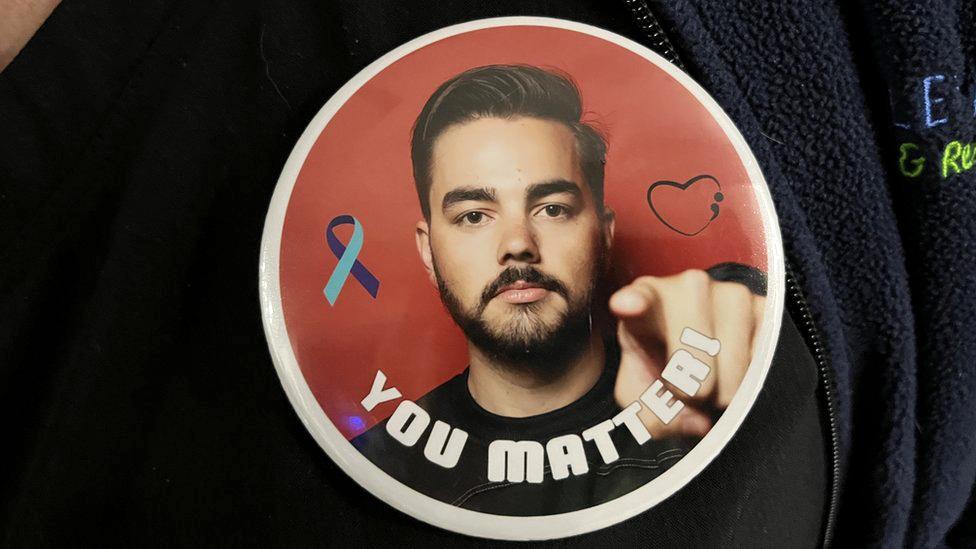

Ben Salas took his own life last April, one of 50,000 suicides registered in the US last year

Warning: contains upsetting material.

Katherine and Tony Salas had no idea their son, Ben, was leading a double life.

"In one, he was planning his suicide," Tony says.

"And in the other life, he was shopping for engagement rings."

"I wish he would have given us the chance to help him," says Katherine, her voice breaking.

"That was the hardest part - I had no way of talking him through it."

Twenty-one-year-old Ben Salas took his own life last April. He was a promising criminology student at North Carolina State University and an aspiring Olympic athlete. He had many friends, a stable relationship and a loving family.

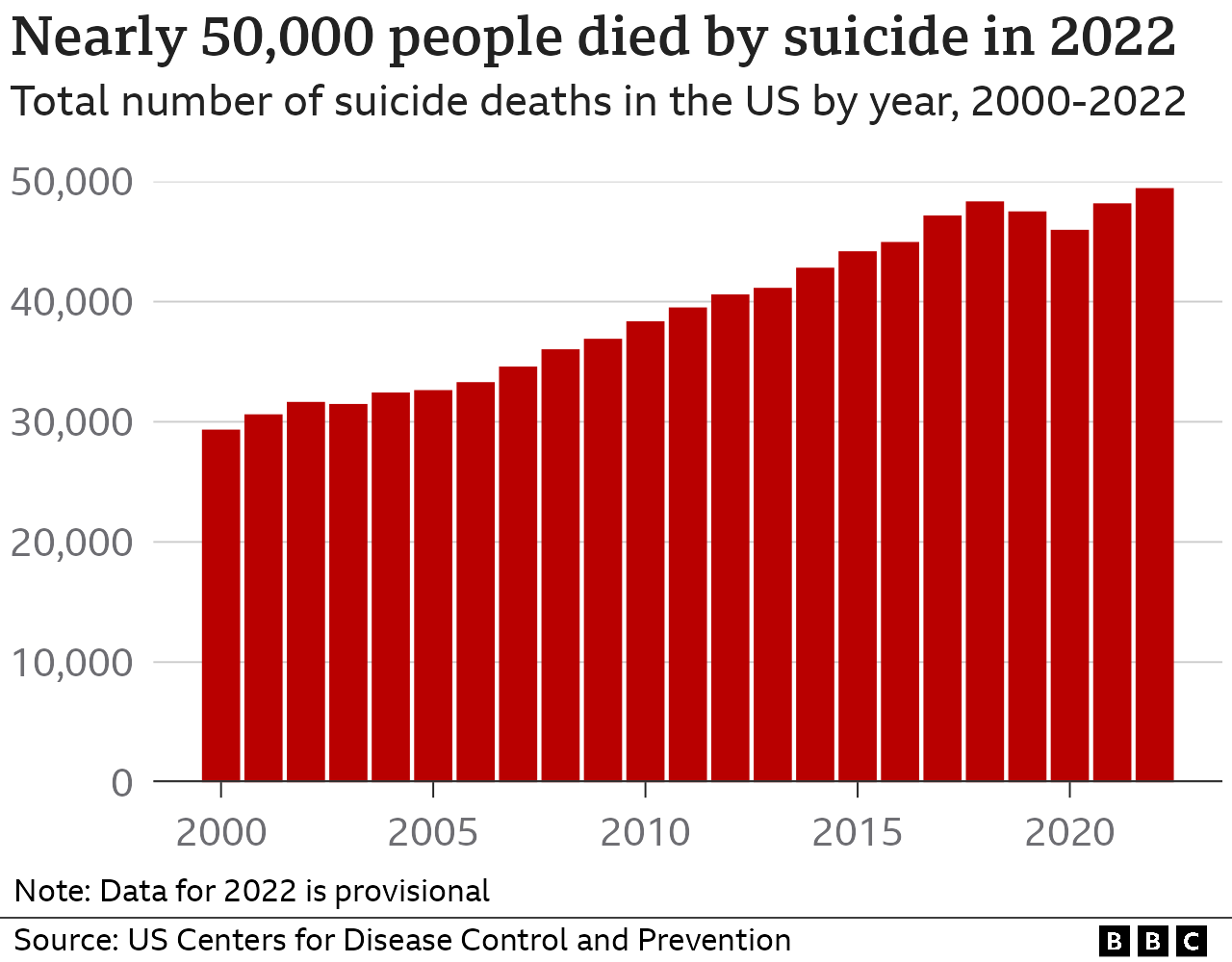

His death was one of 50,000 suicides registered in the US last year - the largest number ever recorded. In second place: 2022, which saw 49,449 suicides.

Crippled with grief, Tony and Katherine have created a "memory wall" to Ben in their front room. His university diploma, awarded posthumously, hangs at the top.

"He was a good all-round person," Tony says. "There's a huge hole in our souls. A part of us is missing."

Katherine and Tony Salas saw no warning signs

But why did Ben kill himself? That's the question the Salas family is struggling to answer.

Ben's parents say their son briefly received treatment for mild depression in 2020, but subsequently reassured them that he had fully recovered.

"There weren't any of the typical indicators that you would expect in a kid that was continuing to struggle mentally. He wasn't withdrawn," says Tony.

Ben was close to his parents, speaking to them often. Tony called his son shortly before he died.

"He said 'I'm okay. I'm good.' And then a couple of hours after that he was gone."

North Carolina State University has recently been sent reeling by a series of suicides. In the previous academic year, seven students, including Ben, took their own lives. So far this academic year, there have been three suicides, including one at the end of January.

The high number of suicides has been very difficult on staff and students alike, says Assistant Vice-Chancellor Justine Hollingshead, who is based at NC State's sprawling campus in the centre of Raleigh, North Carolina. She says suicide is a "national epidemic" in the United States that isn't limited to just college campuses.

"If we knew the reason, we would solve the problem. It's not something that we're trying to avoid or not figure out. But there may be no warning signs: individuals don't tell their family or friends, they don't reach out to resources and they make that decision. And we'll likely never know why."

NC State has increased the number of counsellors and drop-in spaces, and introduced a system called "QPR: Question, Persuade, Refer" so that students can recognise the signs that friends or classmates are struggling and get them help.

Staff are trained to refer students who habitually skip lectures or request extensions to deadlines - in case these, too, are signs that something isn't right.

"I feel like we're doing the very best we can in unimaginable circumstances," Ms Hollingshead says.

"Last year it was a case of get through and survive, provide support and hope that you can save a life."

NC State is asking students to "Question, Persuade, Refer"

Raleigh is known as "the City of Oaks" and NC State's red-brick university buildings are nestled among them. The student union, known as Talley, is a multi-storey beehive of cafes, study areas and shops.

"I was in the dorm of the first one that happened." says one student, Lorelai. "I think a lot of kids our age have anxiety about the world. There are constant things that aren't getting better, and life is expensive."

Brody, a computer science student, says he's aware of the help available from emails the university sends out frequently.

"They're putting more of an emphasis on mental health problems," he says.

Other universities, across many different states, are experiencing a similar trend. And suicide is now the second-leading cause of death, external among Americans under the age of 35, according to the Centers for Disease Control, America's health protection agency.

The Covid pandemic could be a contributing factor, says Dr Christine Crawford, a psychiatrist and associate medical director at the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

"It caused this significant hit on our young people in terms of acquiring the social skills and tools that they need," she says. "They were at home, they were disconnected from their peers and from the elements that are so critical for healthy development in a young person."

Young people who spend a lot of time "wrapped up" in their gadgets are constantly bombarded with images of war and polarising political messages, which can lead to anxiety and depression, according to Dr Crawford.

In December 2021, the US surgeon general issued a rare public health advisory on the rising number of youth attempting suicide, singling out social media and the pandemic, which had "exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced".

Calls to 988, a national suicide helpline, external with more than 200 centres across the US, increased by 100,000 per month in the last year alone.

One centre in the state of Maryland is currently expanding its staff from the 150 operators who already work there.

Operator Josue Melendez says many calls come from younger males, starting at age 15 and going up to 35 or 40, and university students.

"The stress of having to pay for [university], the economy as well, all that can be stressful for one person to take in," he says.

The parents of Ben Salas have created a memory wall

Back at the Salas family home, Katherine agrees young people are struggling with financial pressures.

"Every safety net that past generations had has been taken away. I think that a lot of young people feel very insecure about what their future holds for them," she says.

She wears a badge pinned to her top featuring a picture of her son and the words "You Matter".

"I wear it every day, over my heart, because that's where Ben is," she says, fighting back tears.

They want to raise awareness about "something that he didn't have control over - depression".

Mental illness is stigmatised in the US, they both say.

"We need more people to talk about it," says Tony. "If it can happen to us, then it can happen to somebody else."

Katherine agrees: "Don't settle for 'I'm OK.' An 'OK' may be an OK, but a lot of times it's not."

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this story you can visit BBC Action Line. Help and support outside the UK can be found at Befrienders Worldwide, external or you can call the US Suicide and Crisis Lifeline on 988.