The mystery of the man embroiled in a billion dollar gold scam

- Published

A mining company's claim that it had discovered a huge deposit of gold, deep in the Indonesian jungle, led to a scramble to invest in the firm. But all that glittered was not gold, as a new podcast series reveals, and questions remain about the mysterious death of the company's chief geologist.

Warning: This article contains spoilers. It also has references to suicide and graphic content that some readers may find upsetting

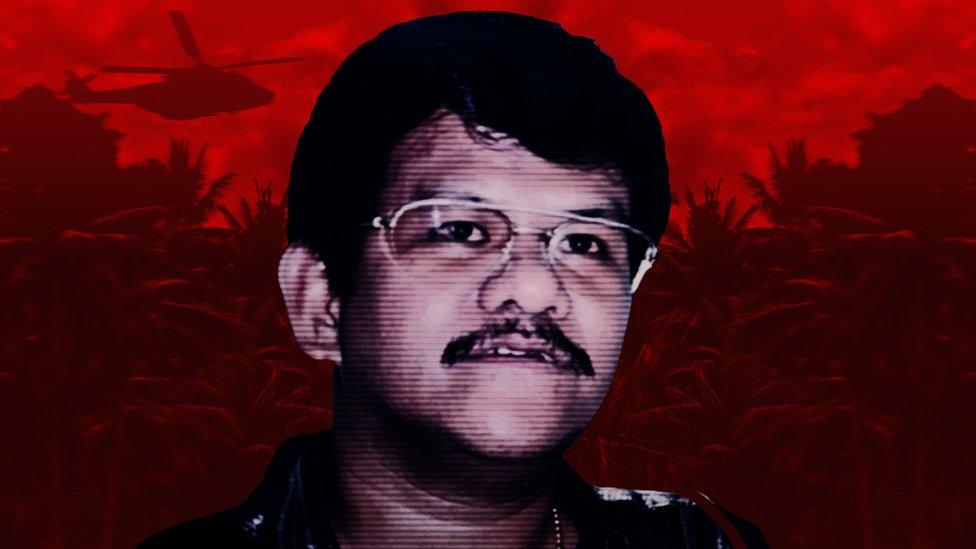

On the morning of 19 March 1997, Michael de Guzman, chief geologist at Canadian mining company Bre-X Minerals, boarded a helicopter flight to travel to a remote jungle site in Indonesia.

It was a journey he had made many times before, to a place where he had reported finding huge deposits of gold.

But this time, de Guzman never arrived.

Twenty minutes into the journey, a rear door on the left-hand side of the helicopter opened and de Guzman had gone, plummeting to his death into the dense foliage below.

The CEO of the mining company announced de Guzman had taken his own life, having been diagnosed with hepatitis B and exhausted from fighting recurring malaria.

Ten years later, Canadian journalist Suzanne Wilton was sent by the Calgary Herald to investigate De Guzman's death.

"I was sent halfway around the world… This story has haunted me ever since," she says.

Now, she is back on the case for a new podcast series - digging deeper into what happened before the fateful helicopter trip.

The remote site was in Busang, in the province of East Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo

De Guzman was born in the Philippines on Valentine's Day, 1956. An apt birthday, as he was often in love. He had three, possibly four, wives all at the same time across different countries.

A man who enjoyed karaoke, beer, visiting strip clubs and wearing gold, de Guzman was an experienced geologist who believed he could make his fortune in Indonesia.

In the 1990s, the country was seen as a land of opportunity for gold prospectors with its rich natural mineral sources, says Wilton.

One Dutchman - John Felderhof, known to many as the Indiana Jones of geologists - believed a remote site in Busang, in the province of East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo, was a goldmine waiting to be exploited. But he needed cash to move forward.

John Felderhof was said to have had a charismatic personality

In April 1993, Felderhof struck a deal with David Walsh, Bre-X Minerals' CEO. Walsh was to sell the dream to potential investors of a site laden with buried treasure.

Felderhof controlled operations on the ground and made it clear he wanted a project partner to help with the search - fellow geologist and friend de Guzman.

But Felderhof, de Guzman and their team only had until 18 December 1993 to drill test holes to see if the gold was really there. That was when the exploration licence granted to them by the Indonesian government expired.

With only a couple of days to go before the final deadline, and two holes dug, there was still no sign of gold. Then, says Wilton, de Guzman suddenly told Walsh he knew the precise spot they needed to drill - the location had come to him in a dream.

The team drilled a third hole exactly where de Guzman had pinpointed - and struck gold. A further fourth hole brought with it the prospect of an even greater find.

The Six Billion Dollar Gold Scam

It was the biggest gold mine fraud of all time - a scam that devastated countless lives. But what really happened?

Listen now on BBC Sounds

And if you're outside the UK, listen to the series wherever you get your podcasts.

For the next three years, work at the site continued. As estimates of the amount of gold that was there grew, so did the number of investors. The price of shares in Bre-X Minerals began to soar, from 20 cents to C$280 (US$206; £163). The company was eventually valued at C$6bn (US$4.4bn; £3.5bn).

Many people in Canadian small towns joined the gold rush, investing hundreds of thousands of dollars of their savings.

But as time went on, the shine began to wear off.

Drilling at the site continued until 1997

In early 1997, Indonesia's then-president, Suharto, ruled that a small company such as Bre-X Minerals could no longer solely own the site and reap its rewards. It had to be shared with the Indonesian government and assisted by a larger, more experienced mining firm. So, a deal was struck with US company, Freeport-McMoRan.

Before agreeing to take on all the financial risks associated with precious metals mining, Freeport-McMoRan needed to do its own checks. Its geologists were sent to drill twin holes in the Busang deposit. Twinning is a way of double-checking gold is present by drilling next to the place it has been found and taking rock samples.

This was standard practice in mining, but had not been done so far by Bre-X Minerals.

The twinning samples were sent off to two different labs, but the results came back the same - no traces of gold could be found.

What could this mean for the people who had invested their savings?

Walsh and Felderhof were informed of the new data by Freeport-McMoRan. They instructed de Guzman, who was at a convention in Toronto, to return to Busang to meet the Freeport-McMoRan team to explain.

De Guzman travelled from Canada via Singapore, where he spent time with his wife Genie, with whom he had a son and daughter.

Michael de Guzman was born in the Philippines

His final hours have since been pieced together by another Canadian journalist, Jennifer Wells.

She says de Guzman spent his last evening in the city of Balikpapan, more than 100 miles (161km) south of the Busang mine, with Bre-X Minerals employee Rudy Vega.

Vega was part of the company's Filipino exploration team and had been due to travel with de Guzman to face Freeport-McMoRan.

According to an account Vega would later give to Indonesian police, the two of them went to a karaoke bar. After returning to his hotel room, de Guzman attempted to take his own life, Vega said.

The next morning, de Guzman and Vega travelled by helicopter to Samarinda, another city closer to Busang.

De Guzman then re-boarded the helicopter to travel to the mine - but Vega did not join him.

Two men were with de Guzman on the flight - a maintenance technician and a pilot. But the pilot was an Indonesian air force pilot - not the usual one who made the trip to the Busang mine. The stop-off in Samarinda was also odd - usually de Guzman would fly straight from Balikpapan to Busang.

After having given an initial statement at the time, the pilot has rarely spoken about the trip. But, says Wilton, he has denied any involvement in what happened to de Guzman and has maintained he did not see what happened.

By 10:30 local time on 19 March 1997, de Guzman was dead.

Handwritten suicide notes were found in the helicopter and, four days later, a body was recovered in the vast jungle.

Journalist Suzanne Wilton visited de Guzman's tomb in Manila in the Philippines

Six weeks after de Guzman's death, the Busang gold dream was over for everyone, leaving investors in despair.

Bre-X Minerals' C$6bn valuation had been reduced to nothing.

An independent report would confirm there was no gold at all at the Busang site. Rock samples dating from 1995 to 1997 were analysed and found to have been tampered with through a process called salting. Fragments of gold from another source had been sprinkled among rock samples via a saltshaker to falsify results.

Almost 30 years later, no-one has ever been held accountable for the scam.

Walsh maintained he knew nothing about it and died of a stroke in 1998. In 2007, a Canadian judge ruled that Felderhof had been unaware of the swindle and found him not guilty of insider trading. The Dutch geologist died in 2019.

That brings us back to de Guzman. Had he taken his own life to avoid having to reveal that he had been the mastermind of the deceit?

His suicide notes raise concerns, says Wilton.

For the podcast, a cousin, once removed, of Felderhof - Suzanne Felderhof - says he had expressed doubt over whether de Guzman could ever have written them.

The notes mention physical ailments which, she says, her relative had never heard him complain about.

Wilton says another suicide note was written to a Bre-X Minerals finance manager who de Guzman didn't actually know. In it, one of de Guzman's wives' names had been spelt incorrectly.

Dr Benito Molino was a member of the Filipino investigative team hired by de Guzman's family to examine the evidence once the autopsy reports had been released.

In the photographs of the body found in the jungle, Molino says he saw bruises on the neck and concluded de Guzman had died by strangulation.

"When he was dead, he must have been thrown out of the chopper in the jungle to make it appear he committed suicide," Molino tells the podcast.

"In big crimes, there will always be a fall guy, so we don't believe that the real mastermind will be identified."

Or was the body even that of de Guzman?

Based on initial descriptions, it would appear the individual had been dead for longer than four days - the time it took for the body to be discovered - says forensic anthropologist, Dr Richard Taduran, who worked with Molino.

De Guzman's wife Genie also says the teeth were intact on the body that was found, and yet her husband had false teeth. De Guzman's dental records have never been released by his family, says Wilton.

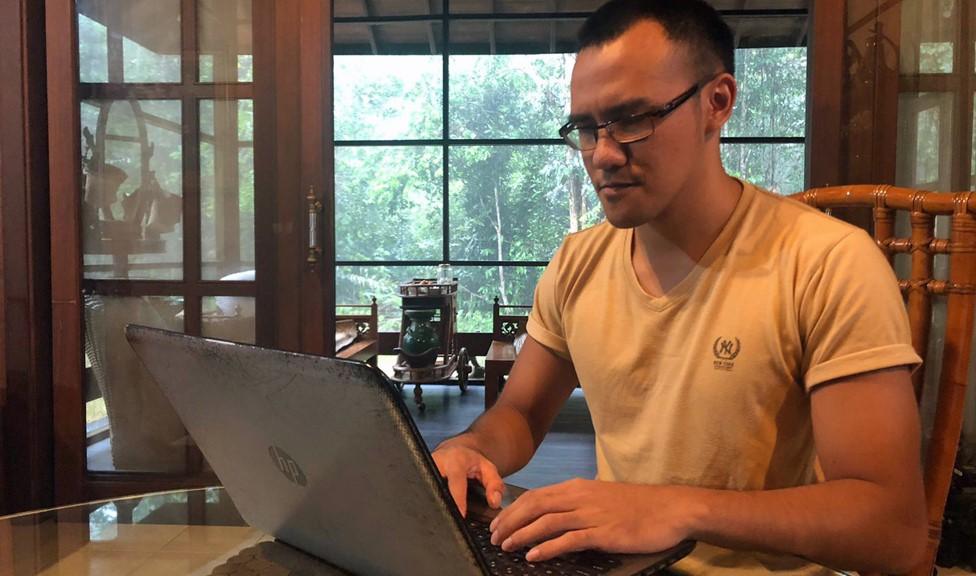

Michael de Guzman Jr is also a geologist

Geologist Mansur Geiger - a friend of Genie de Guzman - says she had told him her husband was still alive and had escaped to South America. Geiger believes he is now living in the Cayman Islands.

Could de Guzman have arranged to pick up a body to take on the final flight to fake his own death? Did he even get on the helicopter at all?

The son he shared with Genie believes his father could still be alive - having been told this by his mother.

He is a geologist, like his father, and is determined to continue his father's legacy - but this time in the right way.

"Maybe I could start my own mines," says Michael de Guzman Jr. "Get some investors and... be the better Mike de Guzman."

Listen to The Six Billion Dollar Gold Scam podcast, made for BBC World Service and CBC by BBC Scotland Productions.