How Kendrick Lamar and Drake changed rap beefs forever

- Published

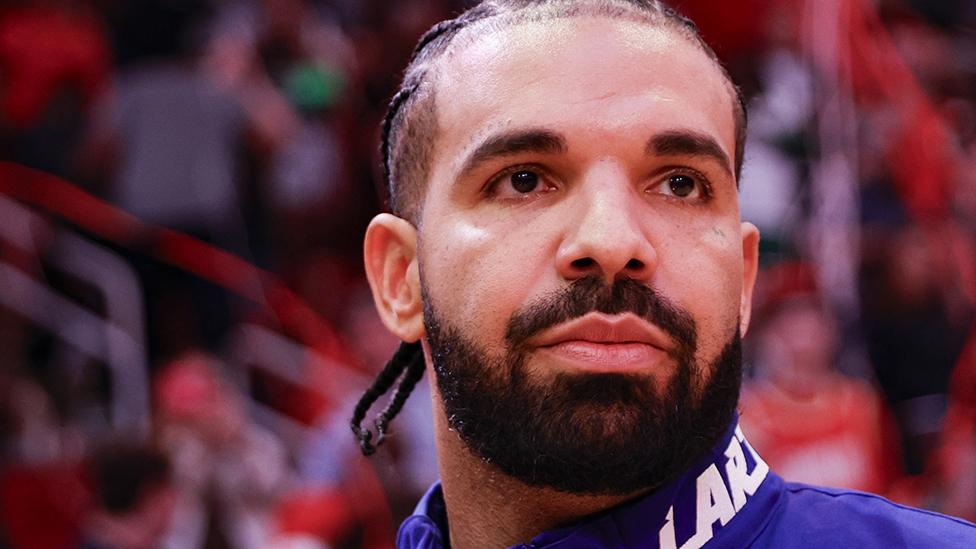

Kendrick Lamar and Drake are such huge stars that their rap beef is practically unparalleled in modern hip-hop

They have been blasted from car stereos on the streets of New York City, played by DJs at nightclubs across the US, dubbed into Chinese on TikTok and inspired merengue songs among Spanish-speaking audiences.

A series of diss tracks from hip-hop's two biggest stars, Drake and Kendrick Lamar, has animated the most high-profile rap beef in a generation, drawing global attention and an avalanche of online discussion and dissection.

The two men's status in the rap world transcends that of the typical artist: Drake owns a record label and has collaborated with the Toronto Raptors and Nike, while Lamar was the first rapper to win a Pulitzer Prize for his level of artistry and produced an award-winning record for the Marvel film Black Panther.

That these two powerhouses would have such a public and angry spat has fascinated not just hip-hop fans but others around the globe - particularly as Drake and Lamar are castigating each other lyrically at such a sudden and blistering pace.

The rap rivals have released nine solo diss tracks aimed at one another in fewer than four weeks, but there are other collaborations and songs produced by other artists that stretch back to Drake and North Carolina rapper J. Cole's collaboration on the track First Person Shooter in October 2023.

J. Cole said on First Person Shooter that he, Drake and Lamar were the "big three" of hip hop. Lamar would reject that idea by rapping that "it's just big me" on record producer Metro Boomin and rapper Future's collaboration on the song Like That.

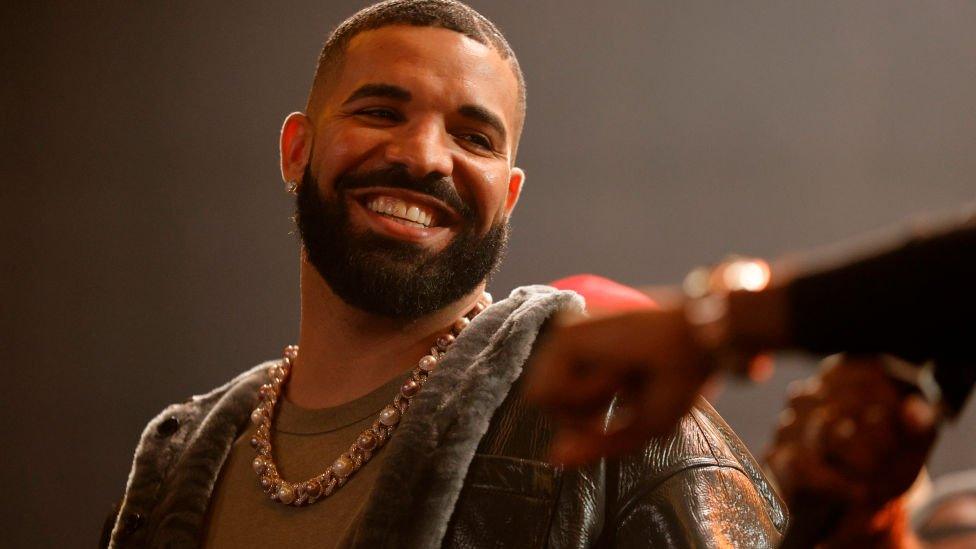

Drake, Kendrick Lamar and J Cole

How times change

In the early days of rap, you might only catch diss tracks on a copied cassette, from an in-the-know radio station, or by seeing a performance at a club. Lamar and Drake's super-charged rap beef made it clear that this has now changed forever.

"I think when you look at this battle, it is going to surpass every other battle because of how it was able to crossover to pop culture so quickly," said Carl Lamarre, Billboard's deputy director of R&B and Hip-Hop.

Even in the recent past, audiences might have had to wait months to hear a feud play out. Jay-Z released the diss track, Takeover, in September 2001 to ridicule fellow New Yorker, Nas. It took his target three months to reply on Ether.

At one time, releasing a diss was an element of performative competition within the hip-hop community. It was used to claim a hip-hop throne, often by rappers who were trying to grow their platform at a local level and to hustle for another show or record contract.

Audiences, in turn, would have to put in work to follow if a rap beef progressed past a night at the club, Bill Stephney, a former executive at Def Jam Records, recalled.

When he was coming up in New York City in the 1980s, Mr Stephney said fans would capture diss tracks on tape, and those who were interested were lucky to get a version that could be listened to. They were often copied hundreds of times from one cassette to another, each iteration decreasing the sound quality until the track was hardly audible.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Stephney said he worked hard to obtain a prized cassette of Roxanne Shante, a female rapper who helped popularise the diss track at 14 years old in New York. She led a series of well-known rap feuds and rivalries called the Roxanne Wars in the 1980s.

The immediacy with which artists are now able to release songs directly on social media, even before they hit digital streaming platforms, means the two rappers can speak directly to each other and to their audiences. Their fans can also then react and respond in real time, and it can rapidly be picked up by popular culture

"Fast forward 40 years [from the Roxanne Wars], and now Kendrick and Drake can create something and rather than having it be dubbed 200 times for New York-area fans to check it out, they can just simply upload it within seconds," Mr Stephney said.

"That 100 million people can consume that so quickly is just such a profound technological change. It's hard to even fathom it."

The two men's diss tracks have produced countless Reddit forums, YouTube explainers and media think-pieces. And the songs that stem from their feud have led the streaming charts in recent weeks.

Lamar's most recent release, Not Like Us, is among the most streamed song in the world at the moment, coming in at #1 on Apple Music in 40 countries earlier this week, and it is expected to debut at #1 on the Billboard charts in the coming days.

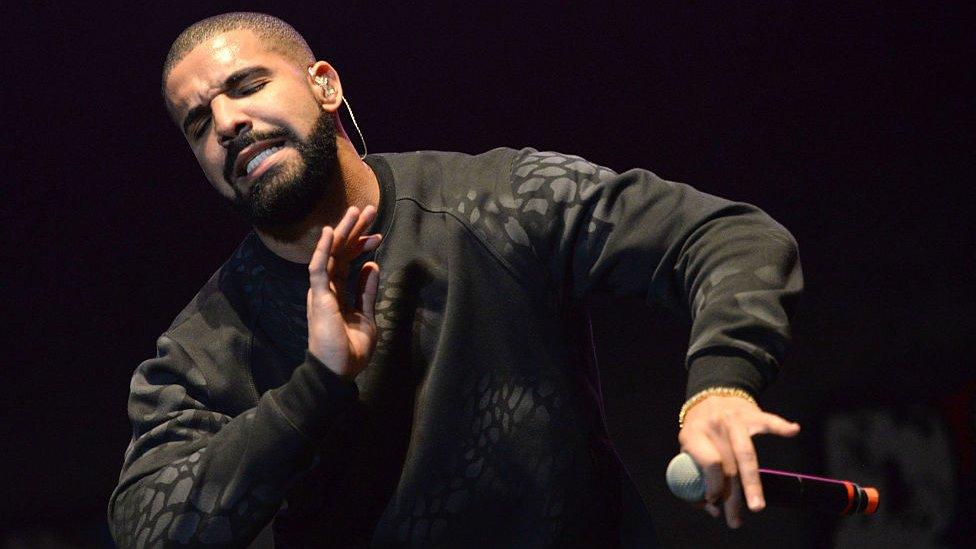

Kendrick Lamar kept the pressure on Drake, at one point releasing three songs in the space of 36 hours

Not Like Us has also been played on US television during an NBA playoff game, it's been heard blasting from the speakers at the Los Angeles Dodgers' stadium and tennis star Naomi Osaka said she listened to it before taking the court at the Italian Open.

Lamar's other diss track Euphoria, meanwhile, was used by President Joe Biden's campaign in a video attempting to throw shade at Republican contender and former president Donald Trump.

"At one time, it was really those people who were really part of the subculture who would know about [rap beefs], and they followed it fervently - but it wasn't accessible," said Pete Nice, the co-curator of the Hip Hop Museum in the Bronx and a founding member of hip-hop group 3rd Bass.

"You had to actually go buy a cassette or vinyl, and you had to listen to the radio to be in the know. Now, all these kids have everything in the palm of their hands."

Serious accusations

While the songs are clearly popular and have delighted fans, they have also showcased the darker side of a beef playing out to an audience of millions. Accusations of domestic violence, secret children and paedophilia have all been shared on the tracks without evidence - and with both men denying the accusations against them.

West Coast rap icon Ice Cube, who famously was at the centre of a number of rap feuds in the 1990s, said in a recent interview with Etalk CTV that both sides have much to lose because of how much attention these diss tracks have received. He noted that in the past there have been times when these disputes have turned violent.

"They're volatile", he said of rap disputes. "You always have to be careful that a beef doesn't turn into a murder. Back in the day, you do a diss record, but it would stay… in the hip-hop community. Now, it's all over the world, all walks of life know what's going on and, you know, some people can't really take that kind of humiliation."

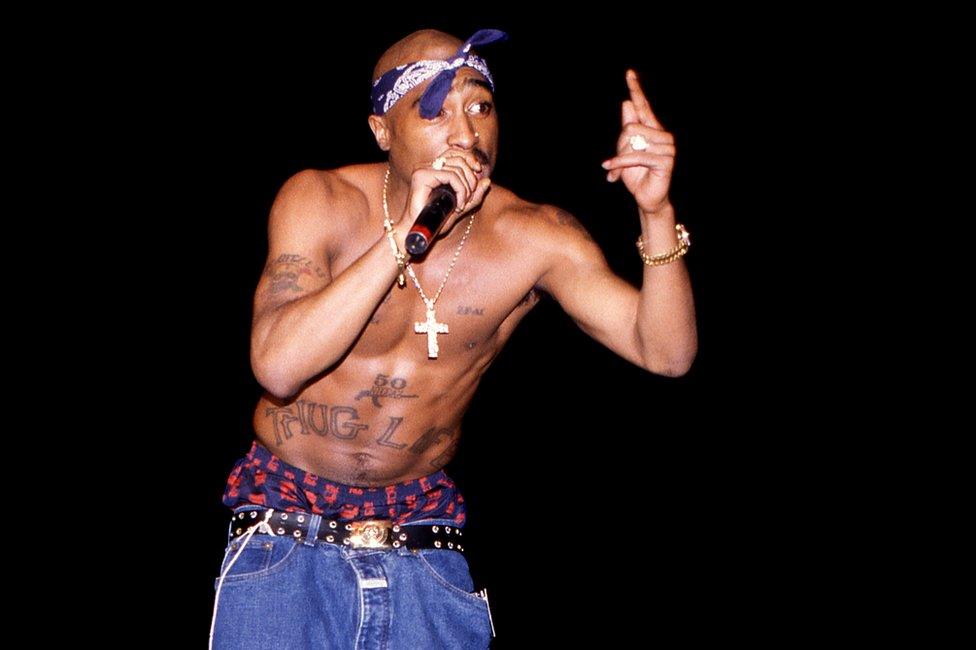

Tupac Shakur, the New-York born rapper, moved to San Francisco in 1988 and became closely associated with West Coast hip hop

Mr Stephney recalled the Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls rap feuds that led to the two men's deaths in the mid-1990s. He noted that a security guard was recently shot outside Drake's home, which has also played host to two other police-involved incidents since the shooting.

While these disturbances have not been connected by authorities to Drake's dispute with Lamar, the former record producer said he fears the two rappers' feud could lead to real-world violence.

"It made absolutely no sense when it happened 28 years ago," Mr Stephney said of Tupac's and Biggie's murders. "I just hope those were lessons learned by these two guys and they see the terrible excuses for violence that occurred at that time."

Tensions seem to have simmered down in recent days, though the public will have to wait to see what effects the beef may have on the stars' reputations.

That does not mean fans and casual observers are not keeping their eyes peeled for another diss track release, however. The last track - Drake's THE HEART PART 6 - was delivered less than a week ago on 5 May. And it is clear that fans want more.

"This is the kind of rivalry that people favour. It's Nadal-Federer, Lakers-Celtics, Yankees-Red Sox," Mr Lamarre said. "These are two different artists with amazing accolades that have two different backgrounds."

"And it just forms a community as people sit around the internet bonfire and wait for that next diss track to be released."

Additional reporting by Regan Morris in Los Angeles

Related topics

- Published9 May 2024

- Published6 May 2024

- Published7 May 2024