Good Friday Agreement: What does it mean for NI after 25 years?

- Published

On 10 April we will mark a historic day - 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement, which helped bring peace to Northern Ireland, was signed.

The landmark deal will be commemorated in a series of events this month, with US President Joe Biden and former President Bill Clinton both planning to visit Northern Ireland to mark the anniversary.

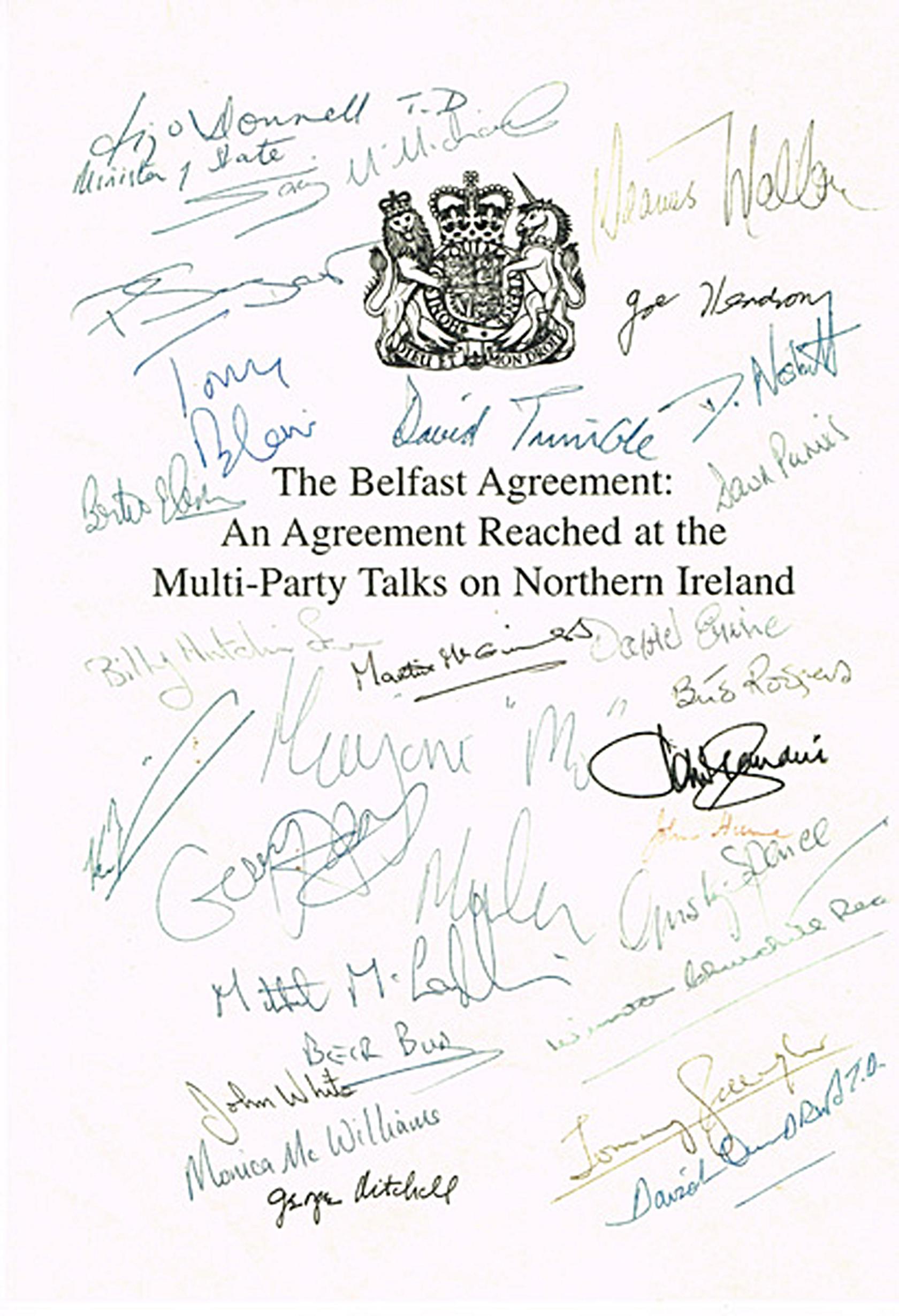

The document, also known as the Belfast Agreement, was signed on 10 April 1998 and set out how many aspects of life in Northern Ireland should change from that point onwards.

It played a major part in bringing to an end 30 years of conflict, known as the Troubles.

The Troubles was a period when there was a lot of violence between two groups - Republicans and Loyalists. Many people were killed in the fighting.

But where did this fighting come from in the first place and how did it lead to the Good Friday Agreement?

What were the Troubles?

The conflict in Northern Ireland dates back to when it became separated from the rest of Ireland in the early 1920s.

Great Britain had ruled Ireland for hundreds of years, but it split off from British rule - leaving Northern Ireland as part of the UK, and the Republic of Ireland as a separate country.

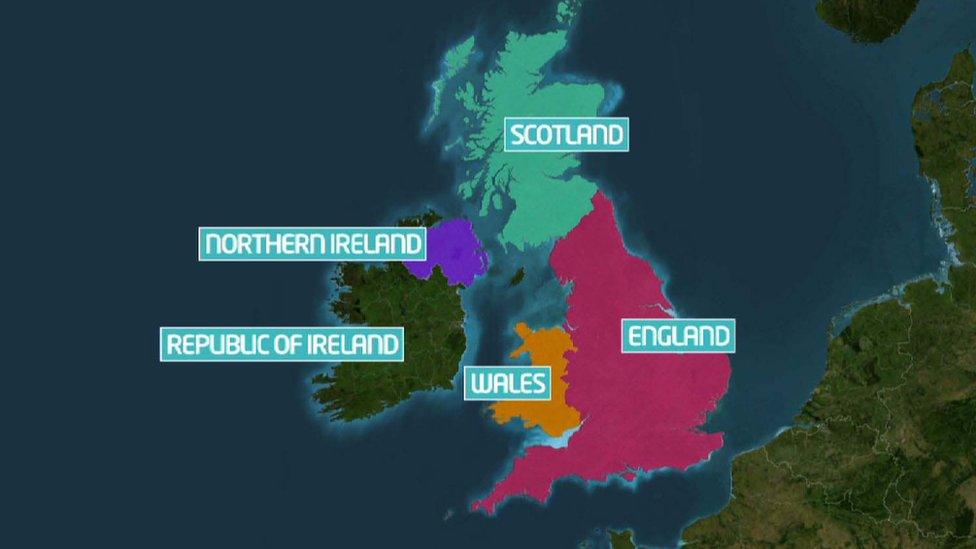

Northern Ireland (in purple) is part of the UK - with England, Wales and Scotland - while the Republic of Ireland is a separate country

When this happened, the population of Northern Ireland was divided in two:

Unionists, who were happy to remain part of the UK - some of them were also called Loyalists (as they were loyal to the British crown)

Nationalists, who wanted Northern Ireland to be independent from the UK and join the Republic of Ireland - some of them were also called Republicans (as they wanted Northern Ireland to join the Republic of Ireland)

Unionists were mostly Protestant, and Nationalists were mostly Catholic.

When Northern Ireland became separated, its government was mainly Unionist. There were fewer Catholics than Protestants in Northern Ireland.

Catholics were finding it difficult to get homes and jobs, and they protested against this. The Unionist community held their own protests in response.

During the 1960s, the tension between the two sides turned violent, resulting in a period known as the Troubles.

This photo shows police fighting with rioters in 1969, in the area of Londonderry

From the 1970s to the 1990s, there was a lot of fighting between armed groups on both sides and many people died in the violence.

In order to deal with the conflict, British troops were sent to the area - but they came into conflict with Republican armed groups, the largest of which was the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

The IRA carried out deadly bombings in Britain and Northern Ireland. Armed Loyalists also carried out violence.

This picture shows the damage to a hotel in Brighton in 1984, after the IRA set off a bomb to try to kill the UK's prime minister at the time, Margaret Thatcher

They included groups like the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Both the Republican and Loyalist gangs were responsible for many killings.

The IRA in particular targeted the police and soldiers from the British army who patrolled the streets. The situation became much worse in 1972, when 14 people were killed by British troops during a peaceful civil rights march led by Catholics and Republicans in Londonderry.

This day became known as Bloody Sunday and for years afterwards many doubted that it would be possible to bring peace to Northern Ireland.

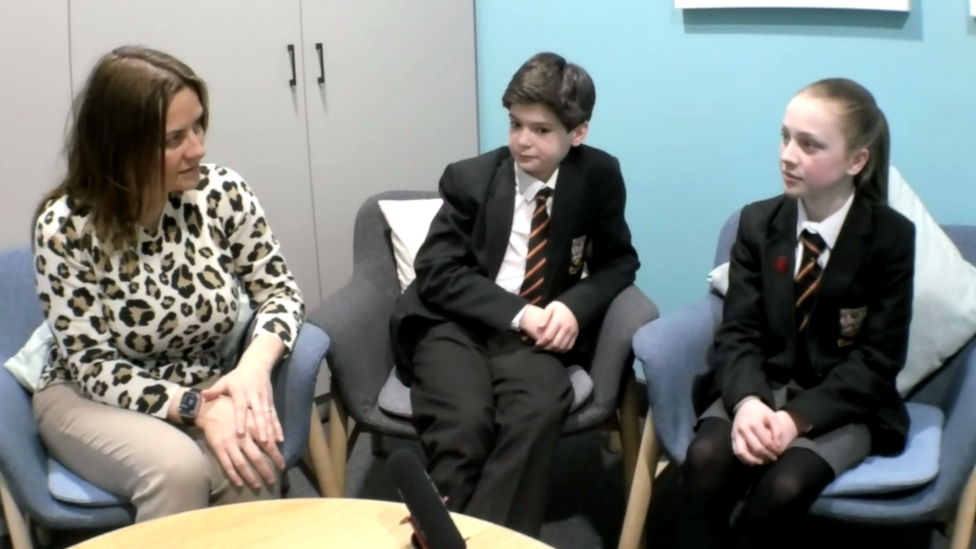

Teacher Ms Lyons and pupils Eli and Alex have been talking to Newsround about their different experiences of growing up in Northern Ireland before and after the Good Friday Agreement

Stacey Lyons lives in Belfast was 13 when the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

She now works as a teacher and shared her experience with Eli and Alex, some her pupils who are almost the same age now as she was then.

She told them: "I'm not sure if I knew a lot about what it meant at that time because I was so young. I didn't really know how significant it would be for Northern Ireland.

"Northern Ireland is so different now to how it was then. I remember when it was dangerous to go into town, there would have been lots of bomb scares - and one day my mum came to get me from school because there was a bomb scare in our street. They had robots and the army to check under cars to see if there was any explosives - fortunately there wasn't that day."

How did the agreement come about?

After years of fighting, the 1990s saw a change in the region, as the IRA announced it would stop the bombings and shootings.

This gave the Unionists and Nationalists the opportunity to try to sort out their problems.

It was not an easy process, and other countries got involved to help the two sides to reach a deal.

In 1998 - after nearly two years of talks and 30 years of conflict - the Good Friday agreement was signed. This resulted in a new government being formed that would see power being shared between Unionists and Nationalists.

This picture shows the Good Friday Agreement being signed by two politicians - the British Prime Minister Tony Blair (on the left) and the Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern

The idea of the agreement was to get the two sides to work together in a group called the Northern Ireland Assembly. The Assembly would make some decisions that were previously made by the UK government in London.

Giving power to a region like this is known as devolution.

Stacey Lyons told Eli and Alex that people had very different views on the Good Friday Agreement.

"There were parts of it that people were excited about and encouraged by - the fact that terrorist and armed groups were going to give up their weapons, that the political parties were going to be working together, and that they would have more power to make decisions for our country.

"But part of the agreement was that people who had been involved in the troubles and were now in prison would be released - and many people weren't happy about that."

The British Prime Minister Tony Blair and an American politician George Mitchell - who led the talks - shaking hands after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement

At 5.30pm on Friday 10 April 1998, an American politician called George Mitchell - who was leading the talks - stated: "I am pleased to announce that the two governments and the political parties in Northern Ireland have reached agreement."

Stacey Lyons told Eli and Alex that she wouldn't have had the chance to go to an integrated school like they do - or even to meet many people from the other community.

She said "Even the youth groups that I went to after school, the other children would have all been Protestants. But I was chosen to be part of a cross-community group that organised for Protestant and Catholic children to meet together and stay with a host family from the other background."

What happened after this?

A copy of the agreement was posted to every house in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland for people to read, before a referendum was held when they could vote on it.

In May 1998, a majority of adults in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland voted in favour of the Good Friday Agreement, which made it official - and the Northern Ireland Assembly took their seats in December of that year.

The front cover of the Good Friday Agreement, signed by the participants

But this didn't completely bring an end to Northern Ireland's problems.

There were allegations of spying and some of the political parties said they couldn't work with each other. Some people opposed to this peace process also continued to be violent.

In 2002, the Northern Ireland Assembly was suspended and its decision-making duties were returned to the UK government.

Five years later, the Assembly was given back power and in 2007, the British army officially ended its operations in Northern Ireland.

However, in January 2017, the deal between the main parties in Northern Ireland collapsed - and Northern Ireland went without a government for three years.

Even though they belonged to different political parties, Northern Ireland's First Minister Arlene Foster (on the left) and Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness - who passed away in March 2017 - worked together as leaders of Northern Ireland, before the arrangement where they shared power collapsed in January 2017

In May 2022, elections to the Northern Ireland assembly took place, but as a new government cannot form without the support of parties from both communities all ministers automatically ceased to hold office.

The region's political parties still disagree and are locked in a stand-off with each other. Many people hope that a peaceful, power-sharing arrangement can be reached again soon.

Although the politicians continue to disagree, there has been no return to the violence seen in Northern Ireland in the past. It is a much more peaceful place and many say that's because of the Good Friday Agreement.

Alex said she would like to see politicians on both sides working together again.

"They're not focusing on what is best for everyone", she told Newsround. "They're just thinking about what will keep them in their jobs. They are thinking about what we need."

Eli added: "It's not good for us to have a government that isn't working, we should have moved past that. If they want to keep their jobs they should work together and compromise."

Ms Lyons said: There are some great leaders with great ideas for change but because the government isn't working it's not setting a good example for us to follow - and there is always a risk that things could slip back.

"We have a long way to go so need to keep moving in the right direction."

- Published21 March 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published10 January 2018

- Published16 June 2016