Sea ice: What is it and why are people talking about it?

- Published

There have been many stories in the news about something called sea ice.

Globally, there isn't as much sea ice as there used to be, and scientists are worried about this.

Find out below what sea ice is and why we're talking about it.

What is sea ice?

Sea ice is frozen ocean water.

Together, the Arctic and Antarctic are known as the Earth's polar regions

It forms on the surface of the water in winter when it's cold.

Generally, in the summer, it melts and becomes ocean again. However, some sea ice stays all year round.

It is found in the oceans around the Arctic (north) and the Antarctic (south).

Most of the world's sea ice is found in the Arctic.

According to the National Snow Ice and Data Center (NSIDC), sea ice covers just over 9.6 million square miles of the Earth. That's about 2.5 times the size of Canada!

Special kinds of boats called 'icebreakers' are able to sail through sea covered with sea ice, by smashing through it, without damaging the boat

It is different to icebergs as these are created on the land from fresh water or snow, which then break off into the sea.

Sea ice actually forms on the water from salty, ocean water.

Why are we talking about it?

Back in 1979, satellites started monitoring sea ice, to keep an eye on how much of it there was.

Sea ice is different to icebergs, as icebergs are created on land, while sea ice forms on the surface of the water

We are talking about sea ice because the satellite pictures are showing that, year by year, there appears to be less and less of it forming in the Arctic.

Not only that, but the speed at which it is vanishing there has sped up.

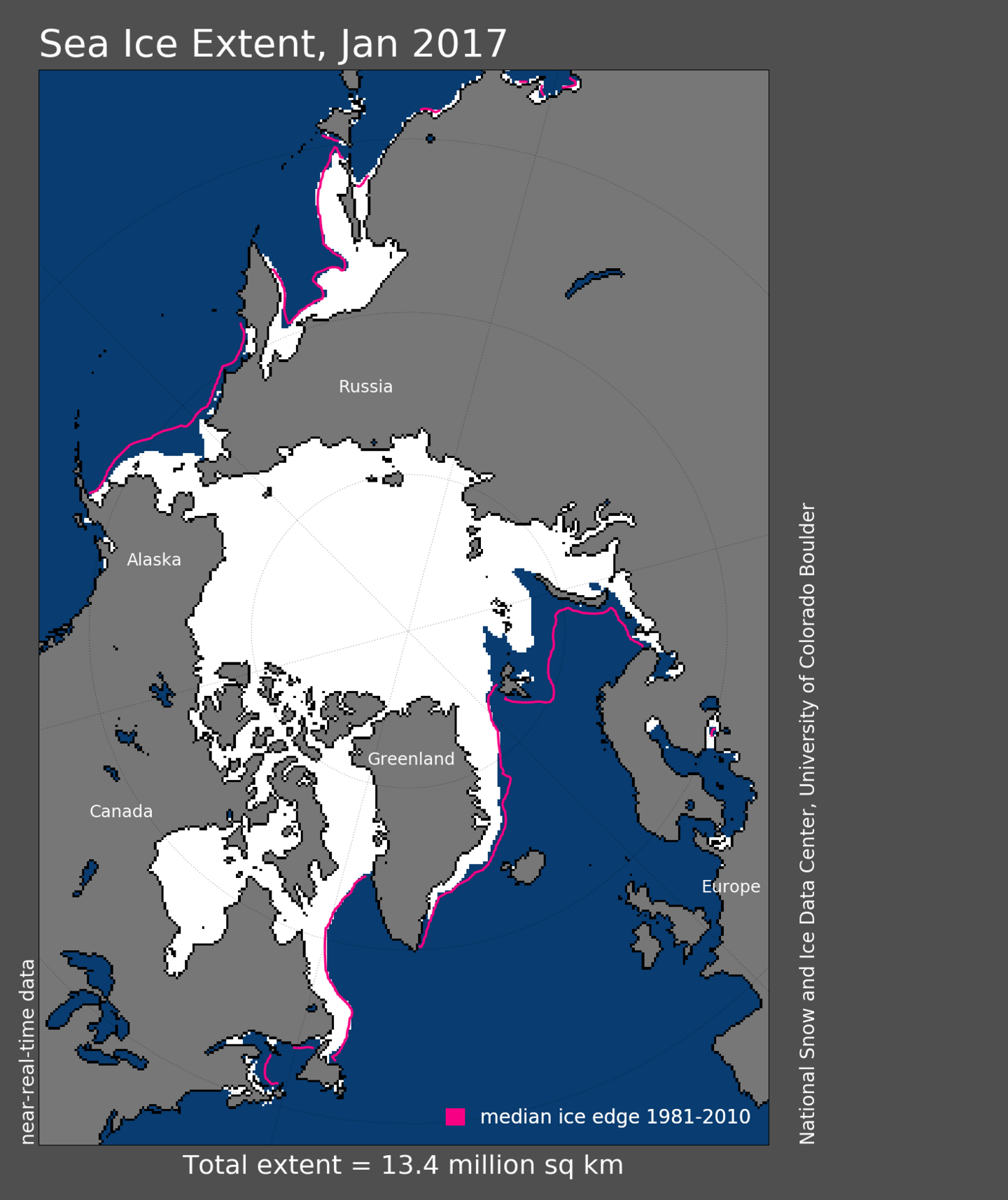

NSIDC reported that in January 2017, there was about 5.17 million square miles of Arctic sea ice recorded.

This is the satellite picture for January 2017: the pink line is a guide to previous levels in the Arctic.

That might sound like a lot, but it is actually the lowest amount of Arctic sea ice recorded for January since it started being monitored in this way 38 years ago.

In fact, it's 100,000 square miles less Arctic sea ice than there was in January 2016.

In the Antarctic the situation is more complicated.

Sea ice in the Antarctic has been behaving differently to sea ice in the Arctic

According to the NSDIC report in February 2017, the amount of summer sea ice in the Antarctic is the lowest on record.

But Dr James Pope, a climate scientist from the British Antarctic Survey, says that's unusual.

"Overall, Antarctic sea ice has been steadily increasing in size, year on year, from the 1970s. So what's happening now is against the trend."

He says this could be important and scientists will need to examine how the Antarctic sea ice behaves in the future.

Why does sea ice matter?

Sea ice is important as, even though many of us will never even see it during our lives, it can have an effect on the climate.

The ice is very bright and reflects the sun's light back into space, meaning that polar regions with sea ice stay cooler.

When there is less sea ice, not as much sunlight is reflected back into space, so temperatures in the polar regions rise.

These warmer temperatures mean more melting, which means less sea ice - and the cycle continues, having a warming affect on the area.

BBC science expert David Shukman talks to Newsround's Leah about this summer's record breaking ice melt in the Arctic.

As the ice melts, it also means there's more water in the sea, so levels can rise which can lead to flooding.

Warmer temperatures in the Arctic and the Antarctic can also affect how the world's atmosphere behaves, as air moves around the Earth.

This can have an influence on things like wind and storms as far away as Europe, where we live.

Even though you will only find sea ice in the polar regions, it can have an effect on the climate in other parts of the world

It doesn't just affect temperature though. Sea ice also influences how the ocean behaves and moves, as cold, polar water from beneath the sea ice sinks and heads to the Equator, while more warm water heads back towards the polar regions.

Finally, melting sea ice can have an effect on wildlife too.

For example, polar bears rely on sea ice to hunt. So if there is less sea ice, they can struggle to get enough food.

Polar bears rely on sea ice to hunt for food

Seals and walruses also use sea ice for resting and giving birth.

Some people living in the Arctic also use it for hunting and transport, so melting sea ice can make their hunting seasons shorter.

What does the future hold?

Just five years ago, the Met Office predicted that, during the summer, the Arctic could have almost no sea ice by the year 2030.

More research is being done to establish what is happening to sea ice and the effect that it could have in the future.

- Published21 August 2012

- Published18 November 2016

- Published28 October 2016

- Published5 November 2016