Climate change: Scientists concerned about future of Antarctic glacier

- Published

- comments

The Thwaites glacier in Antarctica is massive - roughly the size of Great Britain.

Scientists who study glaciers, called glaciologists, have described Thwaites as the "most important" glacier in the world.

But no team of scientists has ever been able to successfully visit and carry out research on it - until now!

WATCH: Scientists travel to world's "most important" glacier

The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration is made up of UK and US scientists working together to investigate whether it might collapse in the next few decades, and how it could affect future global sea-level rise.

They have managed to drill through the ice for the very first time.

What is the Thwaites glacier?

A glacier is a huge sheet of slowly moving ice and the Thwaites Glacier is certainly huge - it covers 192,000 square kilometres (74,000 square miles), and is particularly vulnerable to climate and ocean changes.

Over the past 30 years, the amount of ice flowing out of Thwaites and its neighbouring glaciers has nearly doubled.

It's been called the "riskiest" glacier, and even the "doomsday" glacier.

Satellite data shows that the amount that has melted already accounts for 4% of world sea level rise - a huge figure for a single glacier - and it's continuing to melt at an increasing speed.

There's enough water locked up in it to raise world sea levels by more than half a metre if the entire glacier were to melt.

Scientists want to find out how quickly this could happen.

What research is being done at Thwaites glacier?

WATCH: What do you wear to go to the Antarctic?

Thwaites sits right in the centre of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a huge basin of ice that contains more than three metres of additional potential sea level rise.

It's very far away from anywhere, even by Antarctic standards. It's more than 1,000 miles (1,600km) from the glacier to the nearest research station.

Justin Rowlatt, the BBC's Chief Environment Correspondent, travelled from New Zealand to McMurdo, the main US research station in Antarctica.

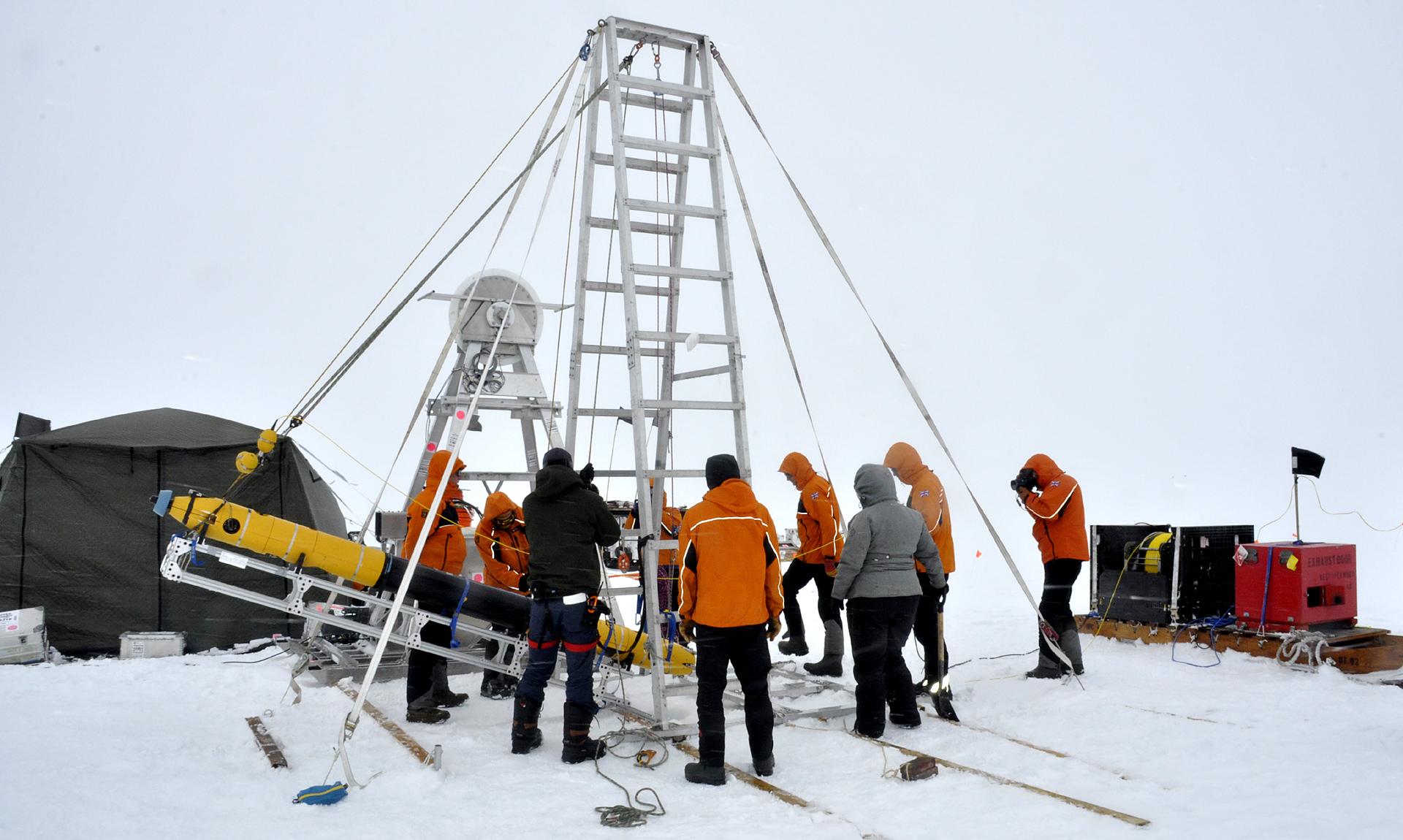

Five teams of scientists and engineers have been working on Thwaites Glacier for the last two months in below freezing temperatures and extreme winds, camping on the ice every night.

The BBC's Chief Environment Correspondent Justin Rowlatt travelled there and spent time finding out about the work that's been going on and what they've discovered.

He saw the teams using hot water to drill between 300 and 700 metres through the ice to the ocean and sediment beneath.

They then sent a small yellow robot, called Icefin, under the ice to collect data about how the glacier interacts with the ocean and sea bed.

This is what Icefin looks like - maybe not quite what you were expecting when we said a robot!

Dr Britney Schmidt from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, said: "We designed Icefin to be able to access the grounding zones of glaciers, places where observations have been nearly impossible, but where rapid change is taking place."

The team have also gathered material that will help them learn more about the history of the glacier, by lowering a very long metal tube through the two holes in the ice.

The project represents the biggest and most complex scientific field programme in Antarctic history.

But it will take years to process all the information the team has gathered and then add the findings into plans that can be used to predict future sea level rises.

Justin has been describing what it was like to fly over it.

He said: "There is no mistaking the epic forces at work here, slowly tearing, ripping and shattering the ice.

"In some places the great sheet of ice has broken up completely, collapsing into a jumble of massive icebergs which float in drunken chaos.

"Elsewhere there are cliffs of ice, some of which rise up almost a mile from the sea bed."

Why are scientists so concerned?

The front of the glacier is almost 100 miles wide (130km) and is collapsing into the sea at up to two miles (3km) a year.

Justin Rowlatt calls this scale "staggering" and says it explains why Thwaites has played such a big part in world sea levels rising.

He describes how the glacier gets thicker and thicker as you go inland, and at its deepest point the base of the glacier is more than a mile below sea level.

Then there's another mile of ice on top of that, making the ice more than two miles thick in total.

It seems that deep warm ocean water is flowing to the ice front, melting the glacier. It is also getting under the glacier.

Justin compares it to cutting slices from the sharp end of a wedge of cheese.

That means as more ice melts away, the surface area left gets bigger and bigger - providing even more ice for the water to melt.

Dr Kiya Riverman, a glaciologist at the University of Oregon, says that is not the only effect.

Gravity means ice wants to be flat, so as the front of the glacier melts, the weight of the ice behind it pushes forward because it wants to "smoosh out".

So, the more the glacier melts, the quicker the ice in it is likely to flow.

"The fear is these processes will just accelerate," she said.

"It is a feedback loop, a vicious cycle."

What do scientists think this could mean?

Justin says that we should know that Thwaites is not going to vanish overnight, and in fact the scientists say it will take decades, possibly more than a century.

But that should not make us complacent.

Professor David Vaughan, the director of science at the British Antarctic Survey said: "A metre of sea level rise may not sound much, particularly when you consider that in some places the tide can rise and fall by three or four metres every day.

"But sea level has a huge effect on the severity of storm surge."

An increase in sea level of one metre means a storm that used to come every thousand years will now come every decade.

Kiya Riverman a glaciologist from the University of Oregon was part of the team drilling through the ice.

Prof Vaughan says we shouldn't be surprised by these changes, as it is all linked to climate change.

He explains that ever-increasing carbon dioxide levels are putting a lot more heat into the atmosphere and the oceans.

Heat is energy, and energy drives the weather and ocean currents.

- Published15 March 2019

- Published15 January 2020

- Published10 December 2019

- Published21 May 2019

- Published29 August 2019