Slavery: What are reparations and should they be paid?

- Published

- comments

On 23 August every year, people around mark the United Nations' International Day for Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

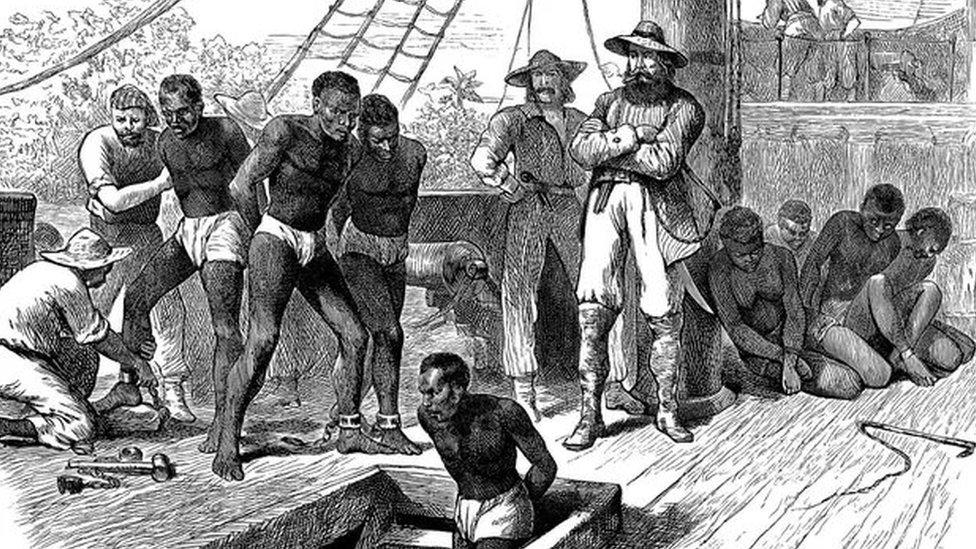

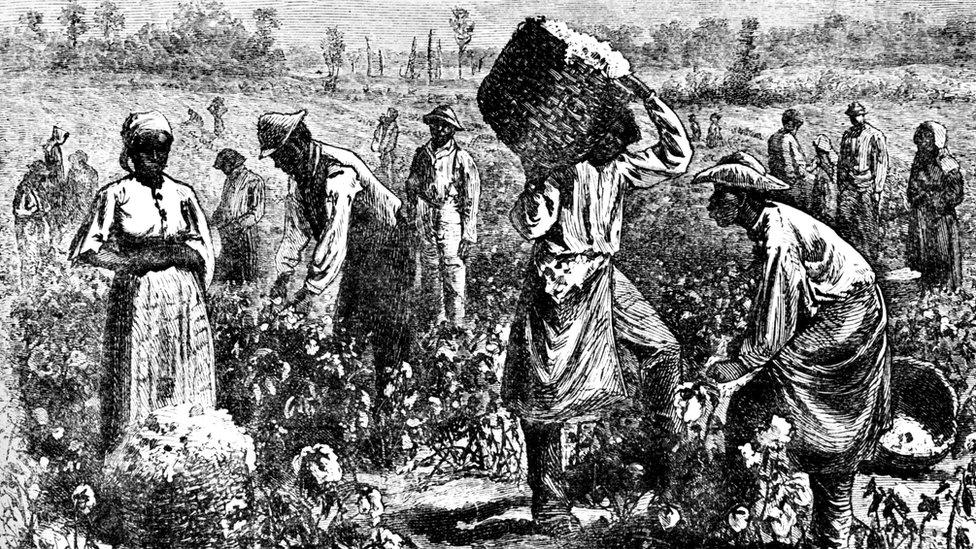

The slave trade was when people were bought and sold as slaves across routes around the Atlantic Ocean.

Slavery used to be completely legal but it was abolished in the UK in 1807 - although it wasn't until a quarter of a century later that slavery ended throughout the British Empire by the passing of a law called the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

This act said that freedom should be granted to slaves in most British territories the following year, although in reality slaves gained their freedom more gradually over the next few years.

When this happened, slave owners were given money by the British government to compensate them for the loss of their slaves, which in those days were considered "property". These payments were known as reparations.

But the former slaves didn't get any money for all the work they had done under slave labour, their lack of freedom, or the horrible conditions they'd suffered.

What are reparations?

Reparation is a word most frequently used in relation to money - given as an apology or acknowledgement that something was wrong or unfair.

The Slavery Abolition Act set out the amount of money that the UK treasury should pay to the 3,000 families that had owned slaves, which ended up being roughly £20 million.

After World War One: Germany and the other countries were to be made to pay for the damage suffered by Britain and France during the war. In 1922 the amount to be paid was set at £6.6 billion.

After World War Two: West Germany agreed to pay $7 billion to the newly created state of Israel where many persecuted Jews were going to live, and in total around $89 billion was paid individual survivors of the Holocaust.

2003: South Africa's post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended reparations for human rights abuses by the apartheid government, although only small amounts were paid.

2013: The UK government agreed to pay out £19.9 million in costs and compensation to more than 5,000 elderly Kenyans tortured by British colonial forces following the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s.

This was a very large sum, around 40% of the government's budget at that time. It had to take out huge loans to be able to raise the funds, which it only finished paying off in 2015.

Nowadays it might seem very strange that people were given money to compensate them for not being allowed to own slaves - something now universally agreed to be wrong and an abuse of human rights.

But, in the past, a large part of the population, including people in very important positions, saw things differently.

For many, their biggest concern was about money and the loss in profits to their businesses after slavery came to an end.

Black History Month: 'My ancestor was a slave'

There were also fears that, without compensation to win over slave owners, could have led to violence or even war between those who supported slavery and those who didn't - something that actually happened in the United States of America.

But as the agreement to pay reparations was made almost 200 years ago, many people living in the UK today didn't even know that slave owners had received reparations and that the debts were still being paid until 2015.

It was only in 2018 that the public became aware, after the government shared a post on social media highlighting the fact, and many people were angry to learn that that their taxes had been used to help compensate slave owners.

What about reparations for former slaves?

More than 12 million Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic to work as slaves. This statue commemorating the abolition of slavery stands in front of the House of Slaves museum in Dakar, Senegal, before being relocated to the "Freedom and Human Dignity" Square, on Goree island, off the coast of Senegal on July 3, 2020

There have been campaigns calling for reparations to be paid to those who suffered as result of slavery.

But as the former slaves are no longer, there is debate as to who the money would go to - their descendants, their communities or countries that slaves were originally taken from?

There are a lot of different views on the idea, as well as much disagreement about how it would work, who should pay reparations, and who should receive money.

Campaigns for reparations

In 2002, campaigners called on governments of the European countries involved in the slave trade to pay off African debt.

Campaigners in the UK argued this would go some way to apologising for its part in the slave trade.

When we talk about reparations, people think that it's about money. But it's about making repairs, be they economic or social, to Africa and for African descendents in Europe.

In 2013 and 2014 several Caribbean countries called on the UK and other European countries, including France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Norway, and Sweden, to pay reparations to their governments.

At the time the UK foreign secretary, William Hague said he "did not see reparations as the answer".

Many countries including the UK have apologised for their role in the slave trade, while others, have expressed regret that it ever happened.

William Hague was the UK Foreign Secretary from 2010 to 2014

Since then. the UK has increased investment in many Caribbean countries, helping to improve infrastructure like roads and buildings, and healthcare, but it hasn't directly addressed the question of reparations.

Other big organisations, like the Church of England and the Bank of England, have also apologised for their historic links to slavery.

Some businesses, who received reparations payments as former slave owners, have promised to pay "large sums" to black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities to try and say sorry.

In July 2020, Lambeth Council in London became the first council to show support for slavery reparations, while each year in Brixton protestors take part in a 'reparations march' on Afrikan Emancipation Day.

What are the arguments for and against reparations for the descendants of former slaves?

Some people held banners calling for reparations during marches on Afrikan Emancipation Day in London earlier this month

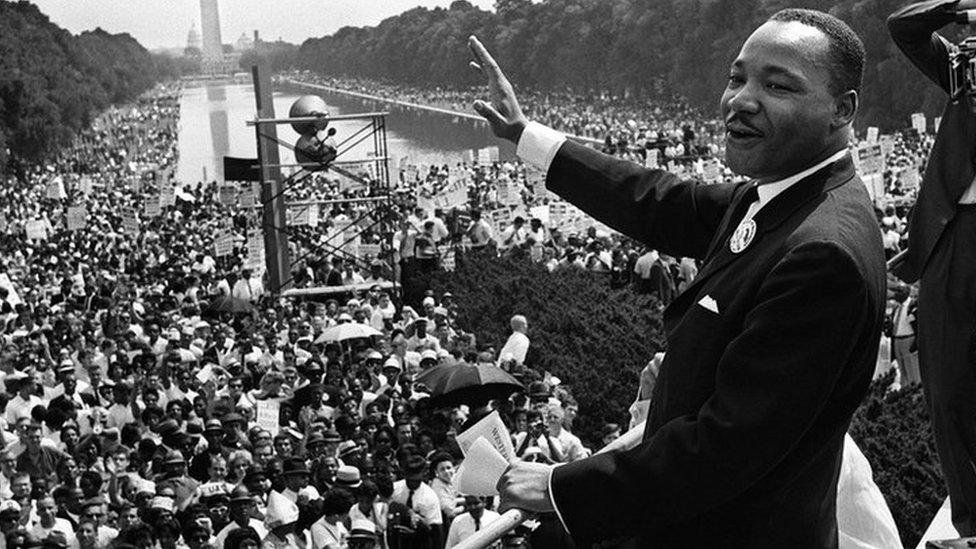

UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet has called for rich nations to make amends for "centuries of violence and discrimination" by paying reparations.

She said: "Behind today's racial violence, systemic racism and discriminatory policing lies the failure to acknowledge and confront the legacy of the slave trade and colonialism."

It's also been argued that, as slavery helped the UK become a world power, some of this wealth should be given back to the descendants or countries where the slaves came from originally.

People have also said that views and attitudes from the time of slavery still have an impact on the present, holding back the descendants of slaves, and so money should be given to address this problem.

In the United States, reparations for slavery has also become a big talking point

Payments would cost governments trillions and as government money comes from taxation and it's been argued that it is unfair and unnecessary to ask people living today to pay for something that happened long before they were born.

Others have said that giving money in the form of reparations doesn't really address the problem of racial inequality, and that the funds that would be spent on reparations could be put to better uses.

Some people whose ancestors were slaves have also said they see the idea of reparations as insulting.

That's because they say no amount of money can make up for the wrongs done during the period of slavery, and it reinforces the view of black people as victims.

- Published22 August 2019

- Published19 June 2023

- Published9 June 2020

- Published2 July 2020