The slave trade: How slavery shaped some of the UK's biggest cities

- Published

- comments

WATCH: Councillor Graham Campbell took Newsround on a tour of his hometown Glasgow to show us how slavery shaped the city's landscape

Slavery has shaped modern Britain and we live with the memory of slavery today. The stately homes, street names, buildings, monuments, and statues across the country tie us to this terrible past.

From London to Glasgow, everywhere you turn you'll see the names of wealthy men printed onto city landscapes. They have been remembered for their work in engineering, charity, art, and politics, but their connections to slavery are less well publicised.

There's now a big debate about whether to remove, rename or reword the buildings, statues and streets in cities across the UK as some people feel they celebrate individuals who participated in slavery as well as Britain's role in this history.

Newsround went to Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow to find out how the legacies of slavery can still be found in the street names, organisations and monuments, which are so familiar to these cities' residents. Read on below.

How has slavery shaped our cities?

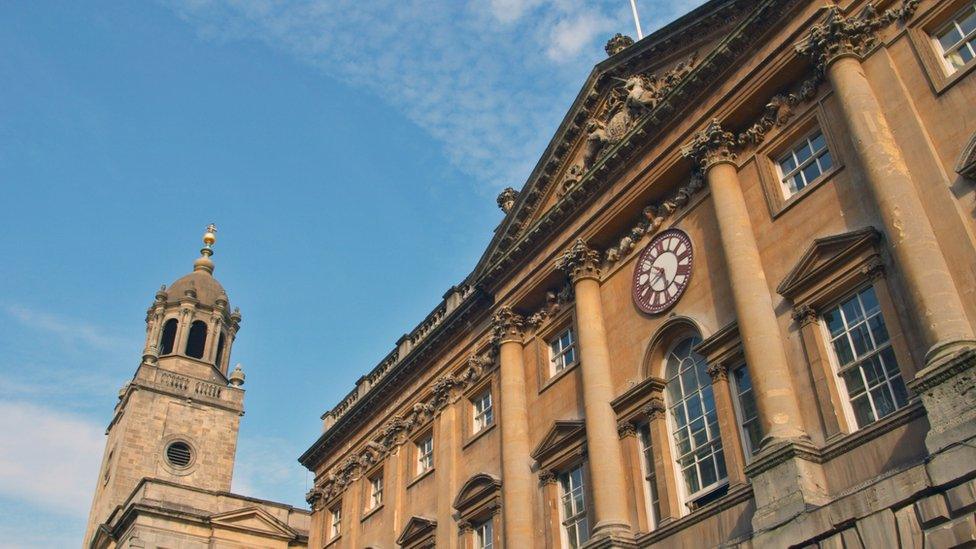

The Exchange was built in 1741-3 to provide a space for Bristol's merchants to buy and sell goods. Much of Bristol's trade depended on slavery and the Exchange was the place where this business was done. The decoration of the building proudly boasts of the international nature of Bristol's trading interests which, directly or indirectly, were associated with the business of slavery. The grand building aimed to demonstrate the city's success

Take a look at the beautiful old buildings in cities across the country.

There's a high chance they were built with the money made by enslaved people's work that allowed Britain's industry to grow and grand architecture to be constructed, which is still standing today.

In September 2021, the National Trust released a report that showed over 90 of the properties it looks after have links to slavery and British colonialism.

And it's not just stately homes. From universities, to town halls, from theatres to banks, the founders of many of these institutions made their money through the business of slavery.

Slavery touched almost every corner of British society.

Black people are central to the story of our cities because their work helped shape our buildings, institutions, culture and history.

What was the business of slavery?

Britain played a leading role in the economic system, which we know as transatlantic slavery.

British slave ships left ports like London, Liverpool and Bristol and travelled to the west coast of Africa where the ship's captain traded goods like cloth and beads in exchange for enslaved African people. These people were then forcibly transported across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and the Americas.

Enslaved people had no rights - they were treated as if they were a form of property or chattel. In other words, people thought they could be treated like any other object or thing that their "owners" possessed.

Special laws were passed in the Caribbean slave societies to make sure that enslaved people were kept in this state. Whether or not you were considered to be enslaved depended on whether or not your mother was enslaved. If she was then you would face a lifetime of slavery as well.

England first became involved in slave trading in the 1560s. Other European nations had already started to make a lot of money from this as they used the labour of enslaved people to build up their empires in the Atlantic world.

The lines on this map show the triangular trade route. Slave ships filled with goods would set sail from Europe and dock in Africa. These ships would then be emptied and filled with enslaved Africans who would make the long journey across the Middle Passage to South America, the West Indies and North America. Goods produced by enslaved people would then be loaded onto ships and sent back to Europe

The movement of goods and people between Europe, Africa and the Americas is known as the Triangular Trade.

More than 12 million Africans were captured and sold into slavery.

They were then tightly packed onto slave ships and travelled for months to the Caribbean or to North and South America. This was called the Middle Passage and many people died on the journey because the conditions were so bad.

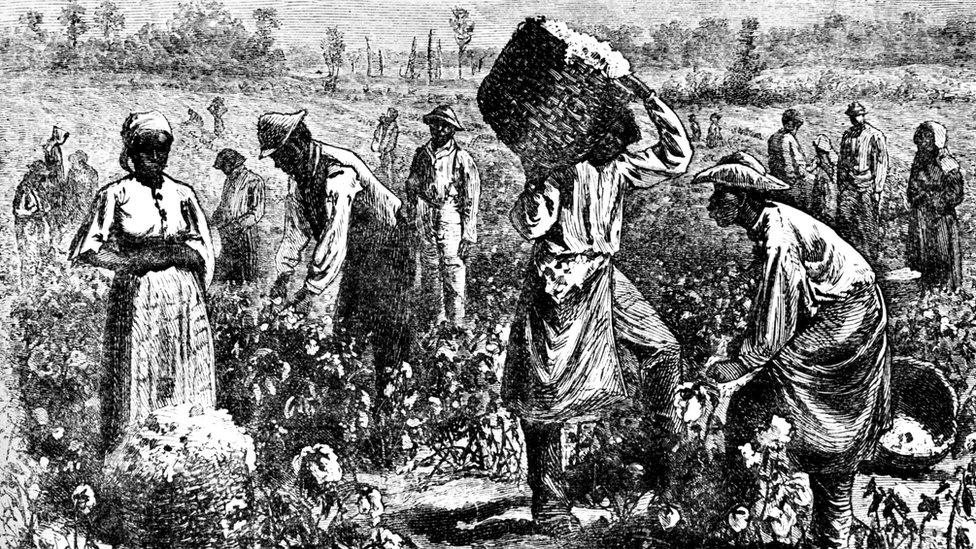

The enslaved people that did survive were forced into work camps known as plantations, where they were forced, usually through the use of violence, to produce cotton, sugar and tobacco. The conditions were so awful that many enslaved people died carrying out their work.

Ships then travelled back to Europe to sell these goods.

Many people became very rich from the system of slavery. This included slave trading, shipping, insurance, slave and plantations ownership, and selling goods produced by enslaved people.

By looking at all the different ways that people could profit from slavery we can begin to see why slavery was so important for the wealth of Britain.

Glasgow

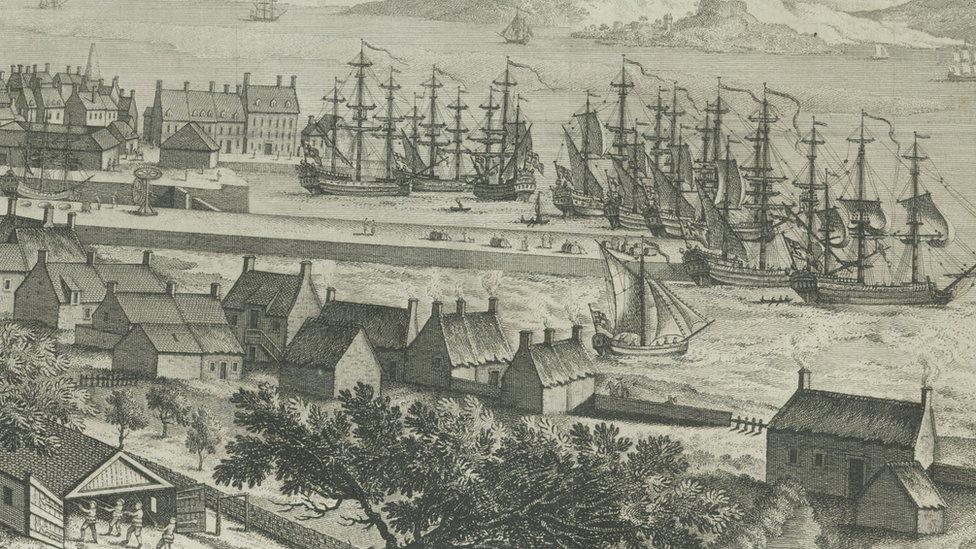

Illustration of Port Glasgow in the 1760s

Glasgow was also one of Britain's most powerful and wealthy cities during the 18th century.

Different people had different roles in the system of slavery and Glasgow's involvement was mainly focused on slave-ownership, making money from the plantations, and the sale of goods made by enslaved people, rather than slave trading directly.

Glasgow became the biggest tobacco importer in the UK and this trade made many Glaswegians very rich.

James Watt

James Watt has been celebrated for his role in engineering, but his connection to slavery is often forgotten

James Watt was an 18th century Scottish inventor who modernised the steam engine.

However, there is a difficult part of his past that people don't tend to talk about - his role in slavery.

Watts' father was a slave trader and made money through the trade in slave-produced goods such as sugar, rum and cotton.

James and his brother John also bought enslaved people to Scotland to sell.

James Watt was so successful he was featured on the back of the £50 note.

Glasgow university even named a building after him, but many people have criticised the university for doing so.

James Watt is a complicated figure, because in later years he rejected slavery. But his son went on to sell steam-powered equipment to plantations in the Caribbean, so the family continued to profit from the system, but in a different way.

John Glassford

Glassford Street was named after the tobacco merchant and slave owner John Glassford

Several streets in the centre of Glasgow are named after 18th century Tobacco Lords. These were a group of Scottish merchants who made huge fortunes by trading in tobacco produced by enslaved people in the West Indies and Americas.

Glassford Street was named after the tobacco merchant and slave owner John Glassford.

The Glassfords owned many properties including Shawfield mansion in the city centre.

John Glassford Family Portrait

Above is a family portrait that shows Glassford and his family at Shawfield mansion.

If you look closely in the top left corner, you can see the faint outline of an enslaved black boy the family would have brought back to Scotland with them.

Gallery of Modern Art

Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art was once the home of tobacco merchant William Cunninghame

Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art used to be the grand home of William Cunninghame, who was a powerful Tobacco Lord and made a lot of money from the labour of enslaved people in America and the Caribbean.

The iconic building was funded with money made from enslaved people's work on tobacco plantations.

Its history might have been forgotten, but the building is still standing and is still connecting Glasgow to slavery that took place over 180 years ago.

Liverpool

WATCH: Levi Tafari took Newsround on a tour of his hometown Liverpool to show us how slavery shaped the city's landscape

By 1740 Liverpool had overtaken Bristol and London as the slave-trading capital of Britain and dominated the trade more than any other port in the whole of Europe.

The raw cotton produced by enslaved people in the Americas was manufactured into cloth in the northern mills near Liverpool.

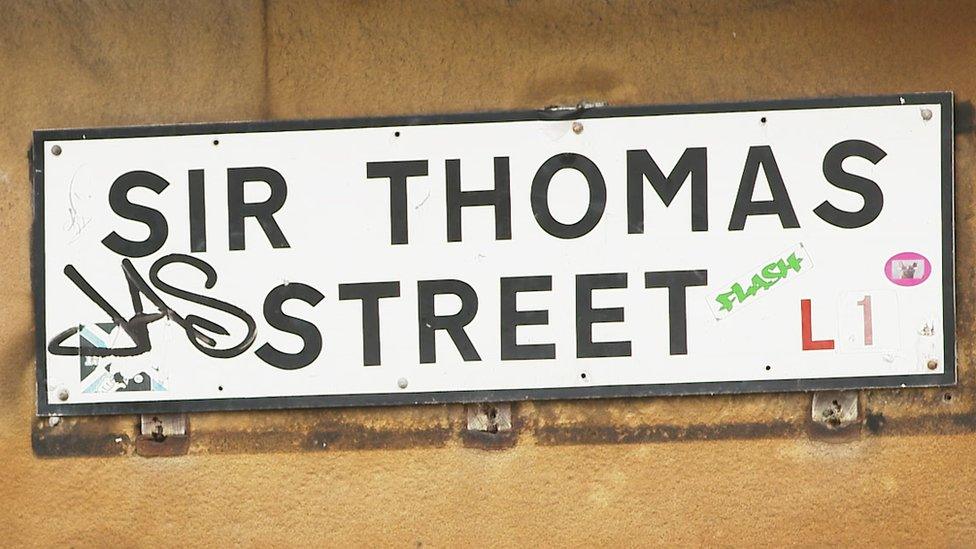

Sir Thomas Street

Sir Thomas Street in Liverpool is named after Sir Thomas Johnson who was the city's mayor in 1695 and profited from slavery

At least 25 of the city's mayors were connected to the business of slavery and several streets in the city are named after them.

Sir Thomas Street is one of them. It's named after politician and businessman Sir Thomas Johnson.

He became mayor of Liverpool in 1695 and is celebrated as the person who helped make Liverpool a major city, because he expanded the port.

This allowed the city to become very wealthy. But this wealth was created through a heavy involvement in slavery.

Sir Thomas was also directly involved in the slave trade himself and was one of the city's earliest slave, sugar and tobacco traders.

William Gladstone

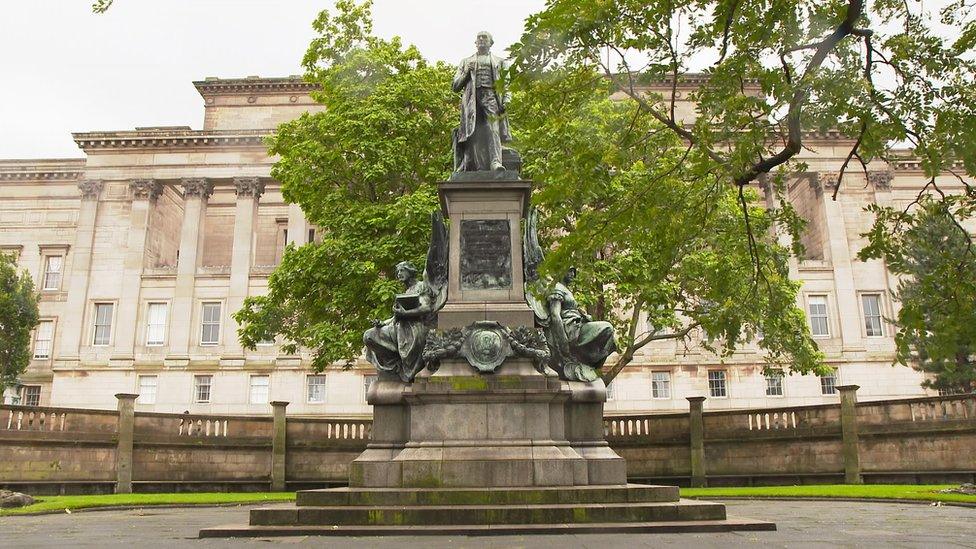

A statue of William Gladstone in St John's Gardens, Liverpool

In St John's Gardens in Liverpool city centre you'll find a statue of Sir William Gladstone. In 1868 he became Britain's Prime Minister.

While he is remembered for his role in politics, many have forgotten his family's connection to slavery.

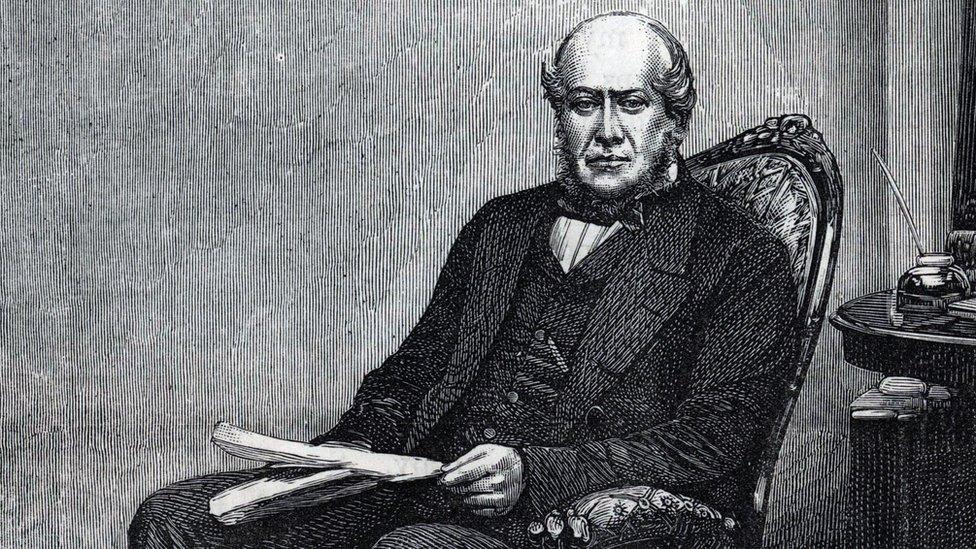

Portrait of Sir John Gladstone, William's father, who made a huge fortune from slavery

William's father Sir John Gladstone was a Scottish merchant, politician and slave trader who lived in Liverpool. He owned enslaved people and plantations in British Guiana and Jamaica.

When slavery was abolished in 1834 John Gladstone received the most compensation from the government because he was one of the largest slave owners in the West Indies.

William Gladstone benefitted from his father's wealth and tried to delay ending slavery.

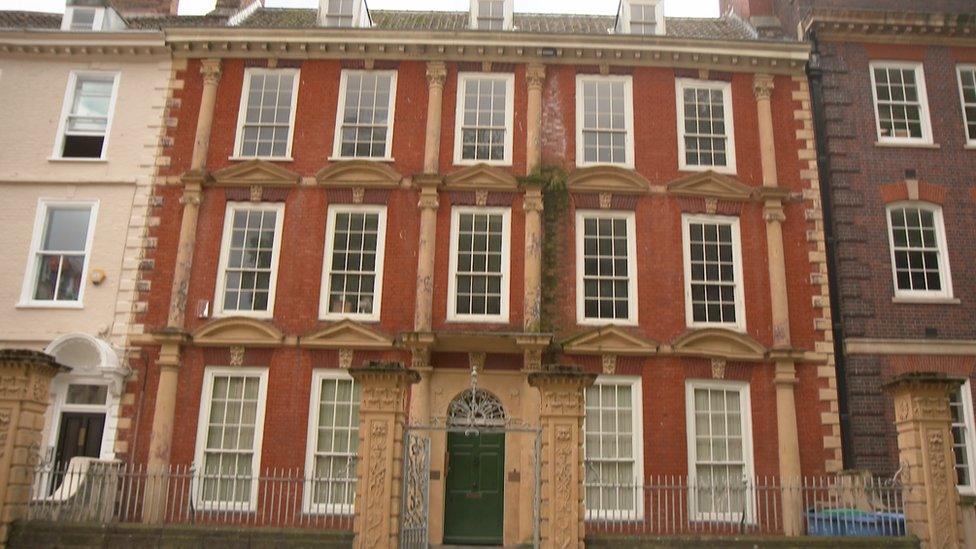

Blackburne House

Blackburne House was built in 1790 and was owned by John Blackburne who was Liverpool's mayor in 1788. His family became very wealthy from slavery

Blackburne House, in Liverpool's stunning Georgian Quarter, is a very impressive building. But the person who built it has a not so impressive back-story.

John Blackburne was mayor of Liverpool and in 1788 he arranged for Blackburne house to be built. It was completed in 1790.

He was one of the most powerful men in the city and his family were slave traders who owned a lot of land in and around Liverpool.

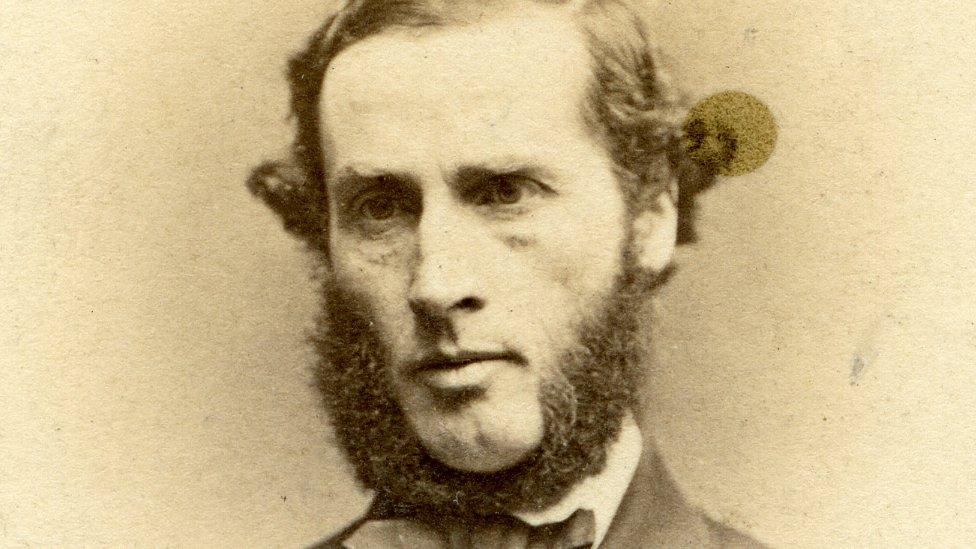

John Blackburne followed in his father's footsteps and served as mayor of Liverpool in 1788

But the history of this grand house took an interesting turn...

While it started off in the hands of slave traders, in 1844 it was bought by George Holt. He was an abolitionist - which meant he had campaigned for the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, which made slavery illegal in some parts of the British Empire.

George Holt transformed Blackburne House into a school for girls

He turned the house into Liverpool's first school for girls. And the school's motto of togetherness and equality was very different from the Blackburne's view on slavery -"Born not for ourselves alone but for the whole of the world".

The building continues to provide education to women.

Bristol

WATCH: Esther Deans took Newsround on a tour of her hometown Bristol to show us how slavery shaped the city's landscape

Bristol played a major part in the transatlantic slave trade and by the late 1730s the city had become Britain's leading slaving port.

Bristol merchants paid for more than 2,000 slaving voyages between 1698 and 1807. These ships carried some 500,000 enslaved Africans from Africa to slave labour in the Americas.

Bristol's involvement in slavery lives on through its architecture, street names and statues.

Edward Colston

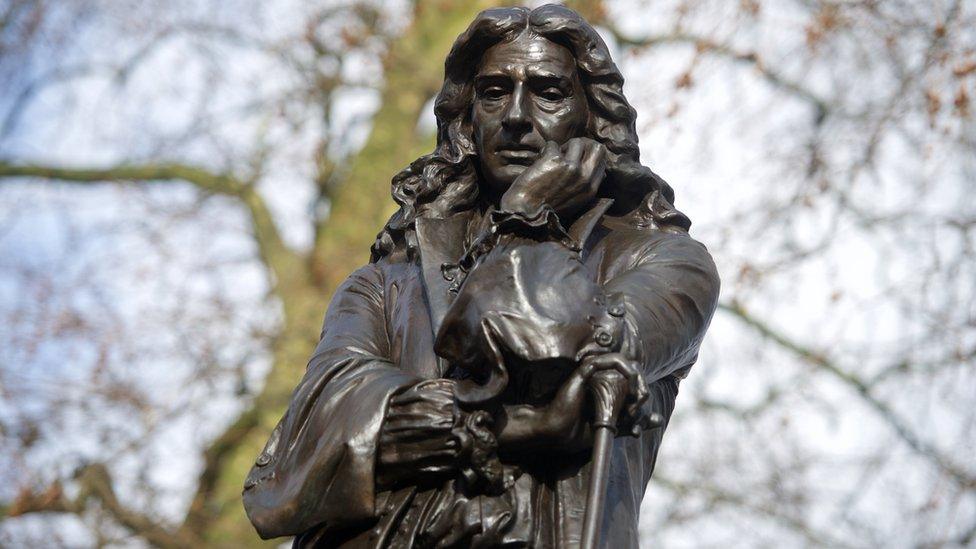

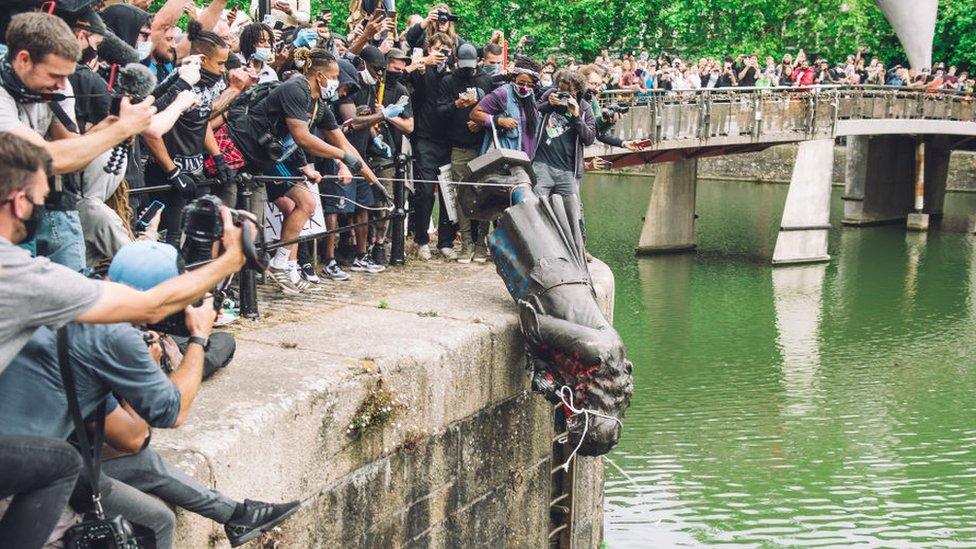

The statue of the slave trader and philanthropist Edward Colston was erected in 1895

Edward Colston was a slave trader in the 1600s and a director of a group called the Royal African Company, which transported about 80,000 enslaved men, women and children from Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas.

It made him very rich and when he died in 1721, he left a lot of money to charities and good causes.

In 1895 a statue of him was erected in the centre of Bristol.

But some groups called for the statue to be removed because they felt it celebrated his charity without making it clear that this generosity was made possible through enslaving African people.

Anti-racism protesters threw the statue of slave trader Edward Colston into the harbour on 7 June 2020

During a protest against racial inequality in June 2020, sparked by the death of George Floyd, some demonstrators in Bristol pulled down the statue and threw it into the harbour where slave ships were once docked. The statue was removed from the harbour and was placed in a museum.

This sparked a nationwide debate about whether it's time for certain statues and landmarks to be removed and renamed.

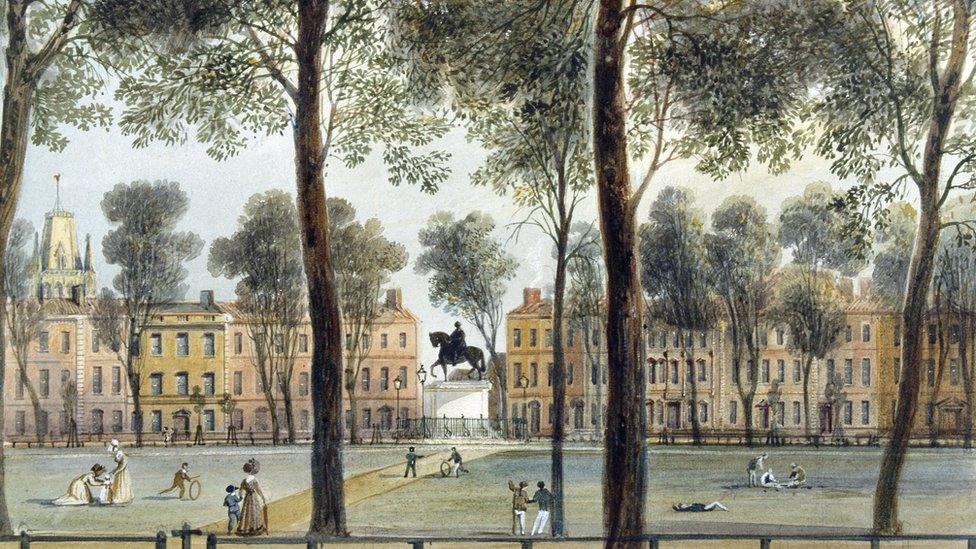

Queen Square

A painting from the 1800s showing Queen Square

Queen Square in Bristol's city centre was created as a green space for rich Bristolians in the early 18th century.

The square is surrounded by beautiful old town houses.

Located close to the harbour, it was a prime location and home to lots of wealthy businessmen involved in slavery.

Henry Bright was one of them. He became Mayor of Bristol in 1771 and was responsible for 21 slaving voyages from the city.

The Bright's made a fortune from trading in enslaved people and things they produced like sugar and rum. They also owned plantations in Jamaica.

The Bright's lived here at number 29 Queen Square

Henry Bright lived at number 29, where he kept an enslaved man whom he named Bristol.

The Bright's continued to be a rich and powerful family in the city. Henry's grandson - also called Henry - became MP for Bristol in 1820 and was also born at number 29.

The great wealth the Bright's made from slavery was passed down through the family for generations.

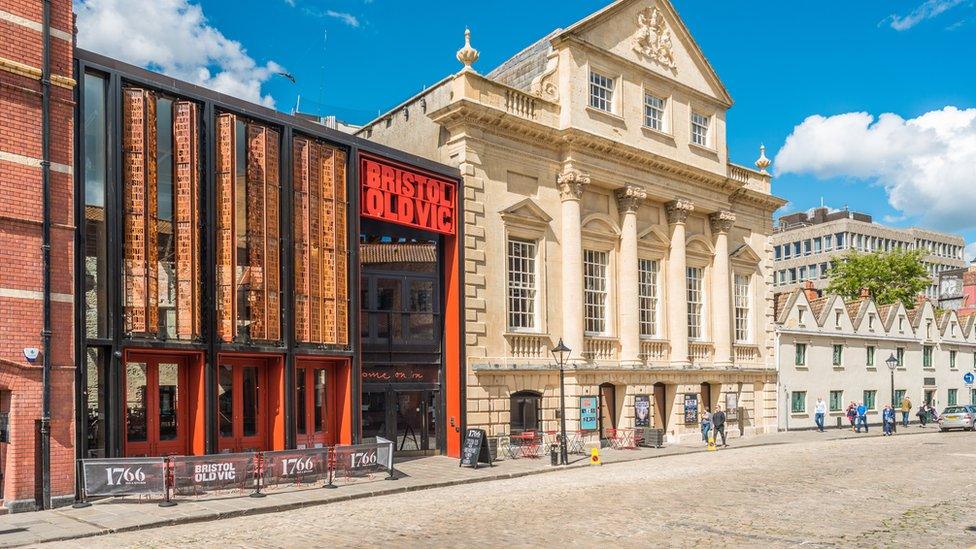

Bristol Old Vic Theatre

Bristol Old Vic Theatre was founded by 50 men and many of them were involved in the business of slavery

Bristol's Old Vic Theatre was built in 1766 and is one of the oldest theatres in the UK.

Originally called The Theatre Royal, it was funded by 50 men, many of whom were slave traders, slave ship investors, and plantation owners.

Bristol's cultural scene began to grow as a direct result of the money made from slavery.

When slavery was abolished in 1834, British slave owners received money worth billions of pounds by today's standards from the government for the 'loss' of their enslaved "property".

This was called slavery compensation and it took until 2015 for British tax payers to pay the debt off. It is seen as one of the greatest injustices in history.

How are our cities changing?

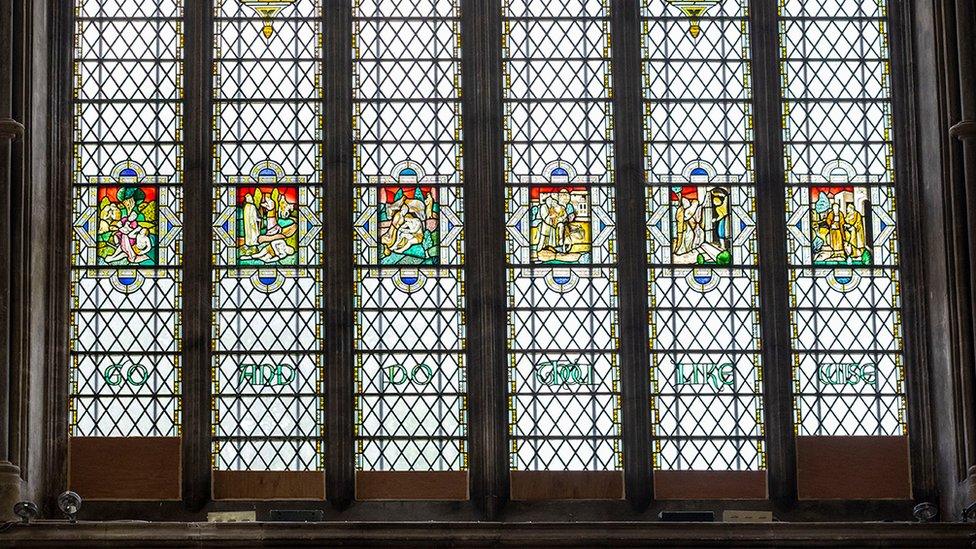

The references to Edward Colston at the bottom of this window in Bristol Cathedral were covered after his statue was removed by anti-racism protestors in June 2020

After the toppling of Edward Colston's statue in 2020, many cities began to reassess the landmarks and buildings that feature the names of people who made fortunes in trades linked to slavery.

Edward Colston's name can be widely seen across Bristol from statues to schools, street names and music venues. But that is changing.

On 16 June a window in Bristol Cathedral, which celebrated Colston, was covered up. And in September, a famous music venue in Bristol called Colston Hall was renamed Bristol Beacon.

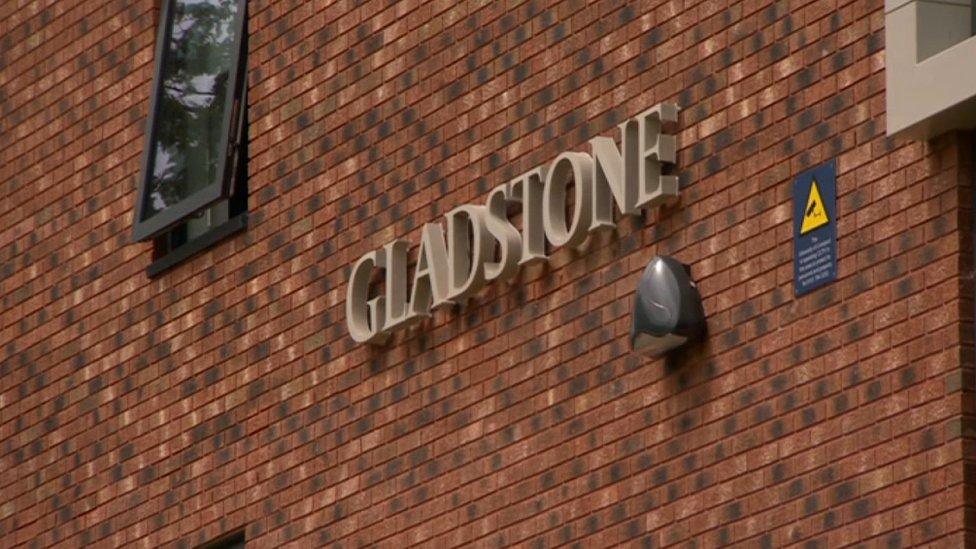

One of Liverpool university's student halls, named after William Gladstone, is going to be renamed

Similarly in Liverpool, the use of William Gladstone's name is being re-evaluated.

One of the university's student halls is named after him. But the university has since agreed to rename it after a group of students asked for it to be changed.

In August this year, Liverpool City Council revealed the first 20 streets in the city that will have plaques explaining their slavery links. Sir Thomas Street is one of them. The council is identifying a suitable location to place a plaque in each street.

A statue of slave trader Robert Milligan was removed in June as a result of anti-racist demonstrations

Elsewhere, in London, Mayor Sadiq Khan asked for a review into the capital city's statues, while a statue of the slave trader and plantation owner Robert Milligan was removed from where it stood outside the Museum of London Docklands.

The call for statues and street names to be changed also took place in Glasgow. In 2020 anti-racism campaigners renamed streets in Glasgow city centre that have links to slavery.

And more than 11,500 people have previously signed an online petition to rename streets in Glasgow linked to this history.

In June 2020 anti-racism activists in Glasgow renamed Wilson Street Rosa Parks Street after the US civil rights activist

Glasgow City Council launched a "major academic study into the city's colonial history and links to transatlantic slavery - the first of its kind in the UK".

Among other things, the study will look at statues, street names and buildings.

Should statues be removed and streets and buildings renamed?

On 15 July 2020, Edward Colston's empty plinth was replaced by a sculpture of Black Lives Matter protestor Jen Reid. The statue was removed by Bristol City Council the day after it was installed. Bristol's mayor, Marvin Rees, said that the future of the plinth would be decided by the people of Bristol

There is much debate about what should happen to the landmarks that make up our cities and towns.

Statues, buildings and street names can be seen as a way to celebrate, remember and tell the stories of culturally or historically significant people.

But who gets to decide what histories are important and how they should be remembered?

It has been pointed out that many statues in the UK don't reflect the country's diverse population and are traditionally focused on white men.

Some of the people who are commemorated with statues are controversial because of the actions, beliefs or views they had when they were alive.

Some people think that as society's values change so should the statues. They think that controversial statues should be replaced with other people who represent different ways of thinking about the past. For example, some people have asked why we don't have any statues that remember enslaved people.

But some people don't want the removal of any statues because they believe that is like erasing history.

Others think that plaques should be placed on buildings and statues that tell the whole history and don't "airbrush" out our past. The plaques would explain why the person is controversial so that everyone can understand that history is more complex than celebrating heroes and hiding away villains - sometimes people are both.

Others say the statues could be removed and put on display in museums so people can still learn about them. That way they can illustrate how society has changed, teach us about key periods in history and reflect lessons that can be learnt from the past.

What do you think?

With thanks to:

Dr. Katie Donington, Senior Lecturer in History, London South Bank University

Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries

M Shed Museum, Bristol

Glasgow Museums

- Published17 June 2020

- Published17 June 2020

- Published17 June 2020