Climate Change: What Narwhal tusks can tell us about Arctic Sea ice

- Published

- comments

Narwhals are the Arctic mammal most at threat from climate change, a new study has found.

A group of scientists have been using Narwhal tusks to help them learn more about climate change. They found the reduction in sea ice and increase of mercury in the water has had a big effect on narwhals.

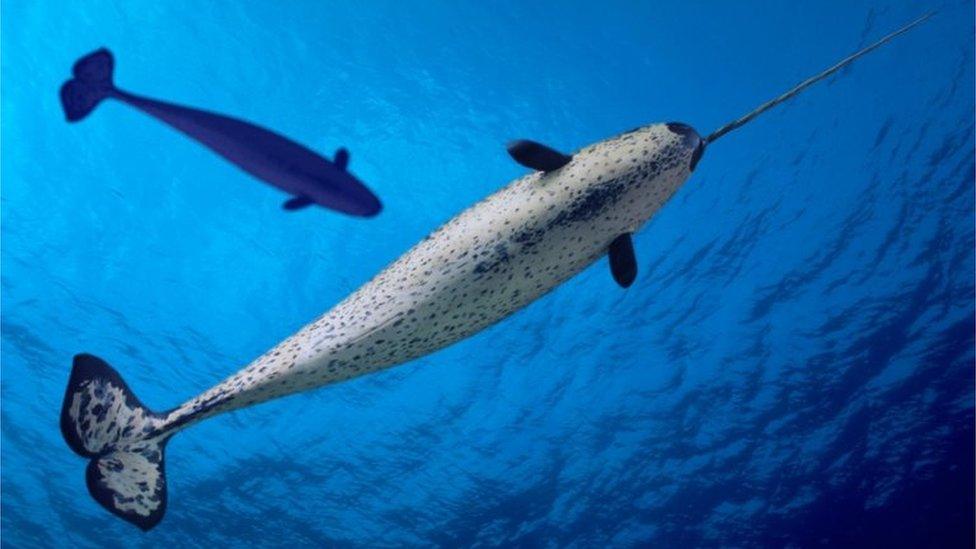

Narwhals are a species of whale that can be found in Arctic waters.

They're sometimes referred to as the unicorns of the sea, because some males have a long tusk which sticks out from their head.

These tusks are pretty special, and work a bit like the rings inside tree trunks. Each year narwhal tusks grow a new layer, and from looking at these layers scientists can learn information about where and what the whales have eaten, and about their environment.

From studying the tusks of ten narwhals living in north-west Greenland, a team of researchers discovered how threats like climate change, melting sea ice and an increase in mercury has affected the species.

What do the results mean?

Narwhals can live for more than 50 years, and as a result of this, researchers were able to study how the climate has changed over this time, thanks to the narwhal tusks layers.

"It is unique that a single animal in this way can contribute with a 50-year, long-term series of data," said Professor Rune Dietz, from Aarhus University in Denmark, who led the study.

"It is often through long time series that we as researchers come to understand the development of biological communities, and such series of unbroken data are very rare. Here, the data is a mirror of the development in the Arctic."

From looking at the layers in the tusks, the scientists were able to learn about what types of food the narwhals ate at that time, and how that changed over the years.

A narwhal's tusk is actually a tooth! Some narwhals have up to two tusks, while others have none. Some tusks can grow as long as three metres!

A timeline of change

Arctic sea-ice in Greenland is very important to the wildlife who live there

The scientists found that, before the 1990s, narwhal's mostly ate Arctic fish like halibut and Arctic cod. These fish are ones that tend to be found where there is lots of sea ice.

Between 1990 and 2000 the sea ice in Greenland began to shrink, and the narwhals began to eat fish that were from the open-ocean instead, like capelin and polar cod.

This new diet shows how animals were moving to new parts of the ocean.

Mercury inrease

From the year 2000 onwards the amount of mercury the scientists found in the narwhal tusks increased dramatically.

The scientists believe this rise in mercury might have been caused by high levels of fossil fuels being burnt in areas like southeast Asia, and a warming climate, which caused changes to the sea ice and mercury cycle.

Mercury is a chemical element that can be found in the air, water and soil.

It is also a type of toxic metal that can cause damage to the human body, including the lungs, kidneys and nervous system.

Mercury is released into the atmosphere when coal and other fossil fuels are burnt.

Once in the environment, mercury can be transformed by bacteria into methylmercury, which can then be eaten by small fish.

"The narwhal is the Arctic mammal most affected by climate change," said Mr Dietz.

"They don't get rid of mercury by forming hair and feathers like polar bears, seals and seabirds, just as their enzyme system is less efficient at breaking down organic pollutants."

The scientists are now hoping to look at other narwhal tusks in museums around the world to help with their research.

"By analysing them, we can hopefully get an insight into the narwhals' food strategy from different areas and periods many years back in time.

"This will provide us with a solid basis for evaluating how the species copes with the changed conditions that it now encounters in the Arctic." said Mr Dietz.

- Published18 March 2020

- Published15 May 2017