School Covid closures affecting millions of kids worldwide

- Published

- comments

Over 400 million children across the world are still missing school because of closures caused by Covid-19, according to the United Nations Children's Fund.

The charity, Unicef, says children in 23 countries are affected and they estimate that 147 million children have missed at least half of their in-person schooling.

Children are a lot less vulnerable to the most serious health effects of coronavirus but school closures have meant that lots of pupils have had big interruptions to their education.

In some of the countries, children don't have access to laptops or video classes which means they don't get much home schooling - and some of them have been forced to find jobs instead.

In March 2020, 150 countries around the world closed their schools in order to stop the spread of coronavirus. Two years on, there are still 19 countries with some closures.

In four others - the Philippines, Honduras, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in the South Pacific - at least 70% remain shut.

"We're seeing children go back who were reading before, who now can't read, who were doing numbers before, who now can't do that," said Catherine Russell from Unicef.

Unicef is particularly worried about children who have been forced to drop out of school and might not be able to go back: "Some children, because their families were so impoverished, were moved into the workforce."

Chloe's story

Chloe, who lives in the Philippines, says she misses her classmates

Chloe lives in the Philippines and she's one of millions of pupils who still have to learn at home.

There are even restrictions on children playing outside in her country.

The 13-year-old has tried to keep up with her lessons online at home.

"I miss the teaching and the classmates and also the activities and schoolwork - just the things that we do in school," she said.

We just need to really make a commitment to take care of these children so that they're able to thrive.

Elin's story

Trinidad and Tobago has had one of the longest partial school closures in the world, with its primary schools only due to reopen in April.

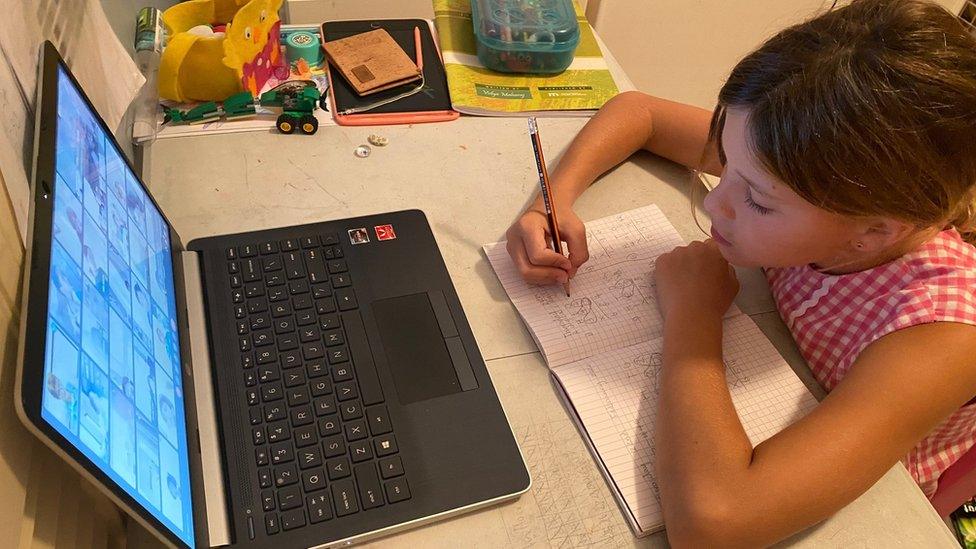

For nine-year-old Elin, nine, it has meant two years of school being reduced to four or five hours a day on a laptop on a small desk in her bedroom.

Elin added she was missing subjects such as music, art and physical education (PE), which just were not the same online. "Sometimes I miss things and I'm afraid to ask," she said.

But she is among the lucky children who have a quiet place to study, a device and broadband, while, others she knows are less fortunate.

Reading, writing and maths

Teacher Lillian Nikaru teaches classes in an outdoor tent

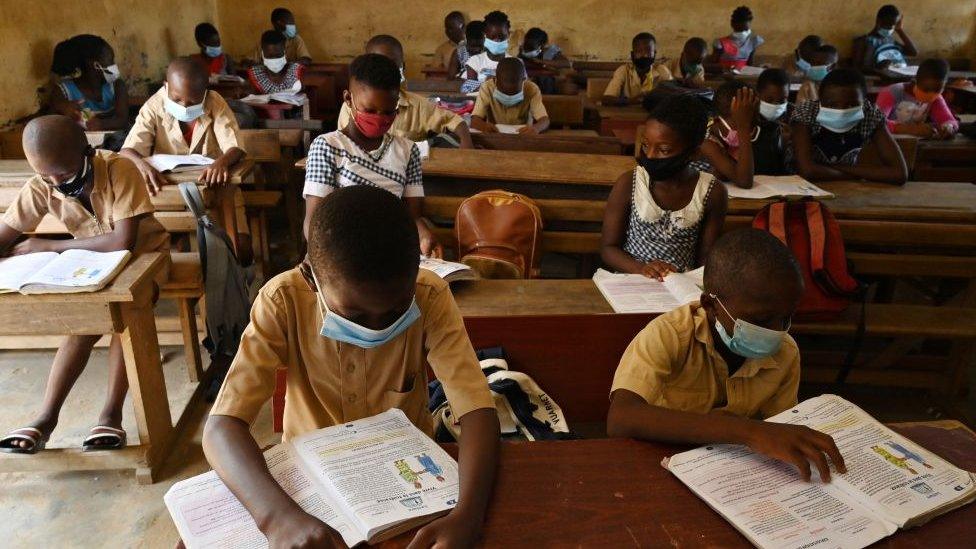

In some countries in parts of Africa, reading, writing and maths levels among school children are the lowest in the world, and that was the case even before the pandemic, according to Unicef.

When schools reopened in Uganda, in January this year, one in 10 pupils didn't return.

There has also been extreme flooding in the region, causing lots of damage to schools.

Lillian Nikaru, who is a teacher in the country, told the BBC: "The gap of almost two years affected them much, so when they resumed they had lost or forgotten many things and we were beginning to teach them afresh."

Teachers like Lillian have been going to family homes to persuade them to let girls return.

What do Unicef want?

Unicef collected information from 122 countries and said that only 60% of those countries had published plans for education to recover.

The charity has warned that Covid has made the deep inequalities in children's access to education a lot worse.

It's calling on countries across the world to invest a lot more money in education,..

"We just need to really make a commitment to take care of these children so that they're able to thrive," said aid Catherine Russell from Unicef.

- Published1 November 2021

- Published29 March 2022

- Published11 March 2021