Spinosaur: Scientists have reconstructed the brain of a million-year-old dinosaur

- Published

- comments

Meet Ceratosuchops - or at least what an artist thinks the spinosaurus looked like

Have you ever wanted to know what was going on inside a dinosaurs' brain?

Well, thanks to scientists at the University of Southampton, now you can!

Palaeontologists (the fancy word for people who study dinosaurs) at the university have made an incredibly detailed 3-dimensional model of a Spinosaurus brain.

They used cutting-edge technology, and the fossils of two spinosaurs called Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops, to make it.

And it's led to some interesting discoveries - read on to find out!

What is a spinosaur?

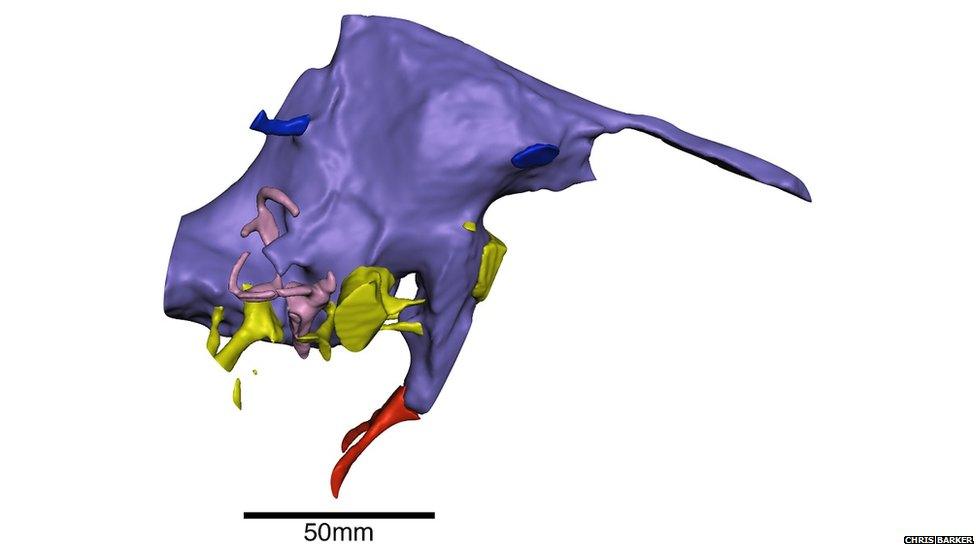

This 3D image is of Ceratosuchops' brain - in it you can see the brain cavity (purple), cranial nerves (yellow), inner ear (pink) and blood vessels (red and blue)

Spinosaurs are part of a group called theropods, which are dinosaurs with hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb - a theropod you may recognise is the Tyrannosaurus Rex.

Spinosaurs are the largest carnivores (meat-eaters) of all the dinosaurs.

Although there are only fragmented fossils, some estimates say they could reach 18 metres long, which would make them longer than a typical T-Rex.

They mainly ate fish and would live near to - and hunt in - water.

If you can't see the quiz at this top of this page, click here.

What did the scientists do?

It's this watery lifestyle that the scientists were particularly interested in.

Spinosaurs have unusual features for theropods - they have long, crocodile-like jaws and cone-shaped teeth that make them very well suited to hunting in water.

This is a model of a spinosaurus skeleton at a museum in China

Unlike their relatives, they'd stride up and down riverbanks to catch prey, including large fish.

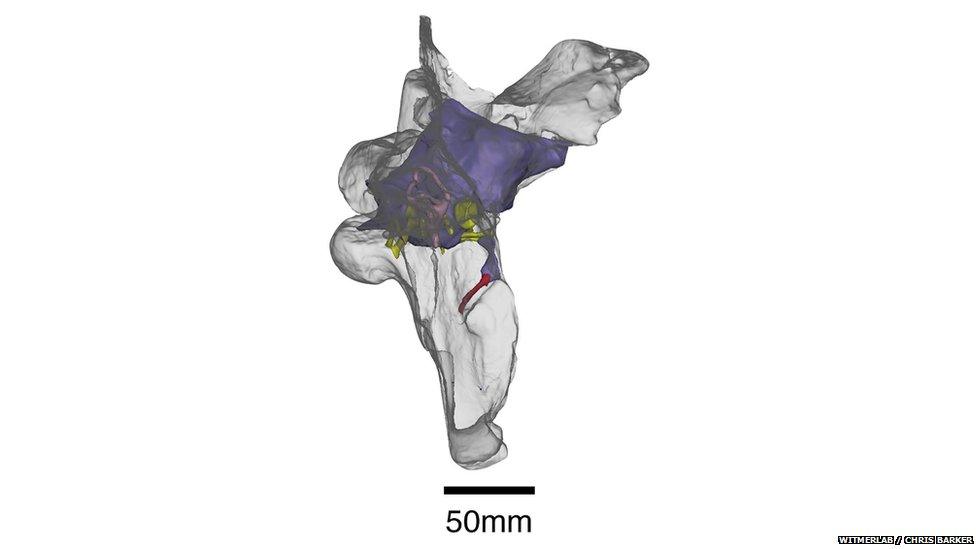

To find out why, scientists studied the skulls of Baryonyx from Surrey, and Ceratosuchops from the Isle of Wight.

They then digitally recreated their brains and inner ears on a computer.

Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops are the two oldest spinosaurs that fossils have ever been found for

They would have been roaming around on our planet around 125 million years ago!

What did the scientists discover?

The researchers found that the olfactory bulbs (the bits of the brain that process smells) weren't particularly developed, and the ear was probably attuned to low frequency sounds, which means they could hear things that were really quiet.

What this means is that while their skulls were specially adapted for fishing, their brains were actually very similar to other theropods, at least at that particular point in history.

This is Baryonyx's close up

The scientists think that later spinosaurs developed specialised brain-functions to better match their daily tasks

One interpretation of what they found is that the ancestors of spinosaurs already had brains and senses suited for part-time fish catching, and that 'all' spinosaurs needed to do to become experts on the water was evolve an unusual snout and teeth.

"Because the skulls of all spinosaurs are so specialised for fish-catching, it's surprising to see such 'non-specialised' brains, but the results are still significant," said contributing author Dr Darren Naish.

- Published22 September 2022

- Published28 February 2023

- Published1 July 2021