Megalodon: Preserved 3.5million-year-old tooth found

- Published

- comments

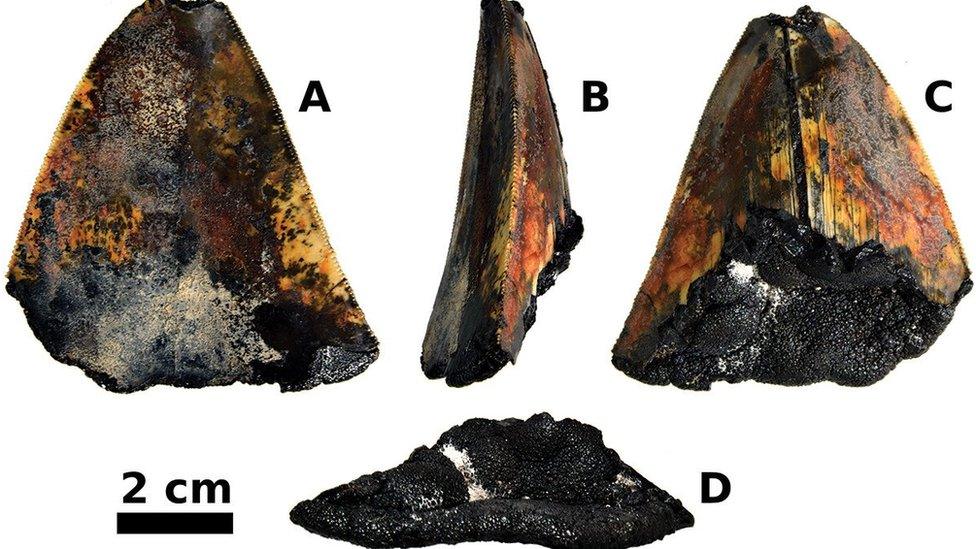

The tooth turned out to be broken but well preserved, with serrated edges and even some enamel

Scientists say they have discovered the world's first preserved megalodon tooth in what would have been the extinct creature's natural habitat near Hawaii.

Palaeontologists at the University of Wyoming spotted the 3.5million-year-old tooth lying more than 10,000 feet below the surface of the North Pacific ocean.

Most megalodon teeth collected in the ocean or from beaches are fossilized, but this one wasn't buried by sand, so it only has a light mineral crust on it.

Because it was only partially fossilized, the team could see details like never before - as the tooth enamel and spongy pulp inside was still intact.

What is a Megalodon?

This fearsome beast - a kind of giant pre-historic shark - roamed the world's oceans between four million and 20 million years ago.

A lot of what is know about them is thanks to their huge triangular teeth, which are often fossilised.

Their skeletons are made of soft cartilage instead of hard bone, which doesn't fossilise well so most of the megalodon fossil record mostly consists of teeth, plus a few vertebrae as those are partially mineralised.

The name "megalodon" means "big tooth" in Ancient Greek, and some of the teeth that have been found are truly massive -16.8cm (6.6in) long, more than double that of a great white shark (around 7.5cm, 3in).

How was the tooth found?

The discovery was made by accident by scientists who were searching the area with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to understand its deep-sea geology and biology.

The ROV came across the seamount, and the tooth was lying among rocks, uncovered and undisturbed.

In its report the team said: "The first in-situ documentation of a megatooth shark fossil from the deep sea highlights the importance of using advanced deep-diving technologies to survey the largest and least explored parts of our ocean."

It was found in a remote location southwest of Hawaii, on the edge of an ocean "desert".

Tyler Greenfield, a palaeontologist at the University of Wyoming, said: "There are areas of the seafloor, especially deep ocean basins far from the mainland, where little to no sediment deposition occurs for long periods of time.

"It's also possible for teeth to be eroded out and reworked into younger sediments, but that probably didn't happen in this case."

Its sharp edges, which have helped it cut through prey, were still intact, suggesting that it hadn't been part of the surrounding rock.

It also hadn't been eroded, which would likely have been the case had it tumbled around in the ocean before being found.

This tooth is not the biggest of its kind to be found - measuring between 6-7cm (2.5-2.6 inches) - but it adds to a growing number that play a key part in tracing megalodon's movements across oceans.

The study has been published in Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology.

- Published3 August 2023

- Published2 July 2023

- Published22 March 2021