How clouds of glitter-sized rods could help humans live on Mars

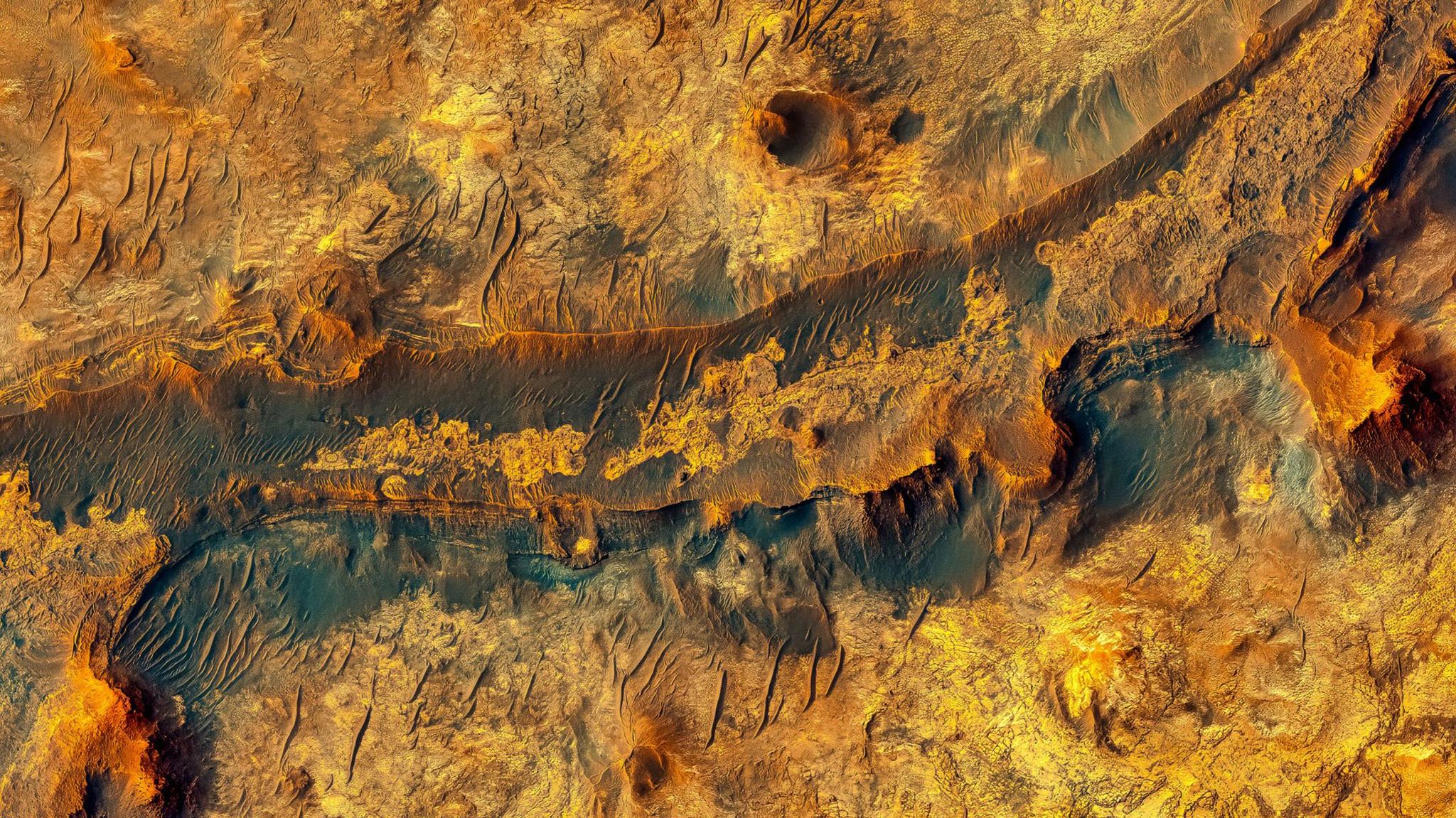

There are dried up rivers on Mars showing there used to be water

- Published

Scientists have long looked at how it might be possible to restore water on Mars, but until now the methods have been very complicated.

A new study claims to have found an easier way by releasing small, glitter-sized iron rods to trap heat in the atmosphere and warm the planet in order to melt its surface ice.

Nasa has been planning to get humans living on Mars by the 2030s.

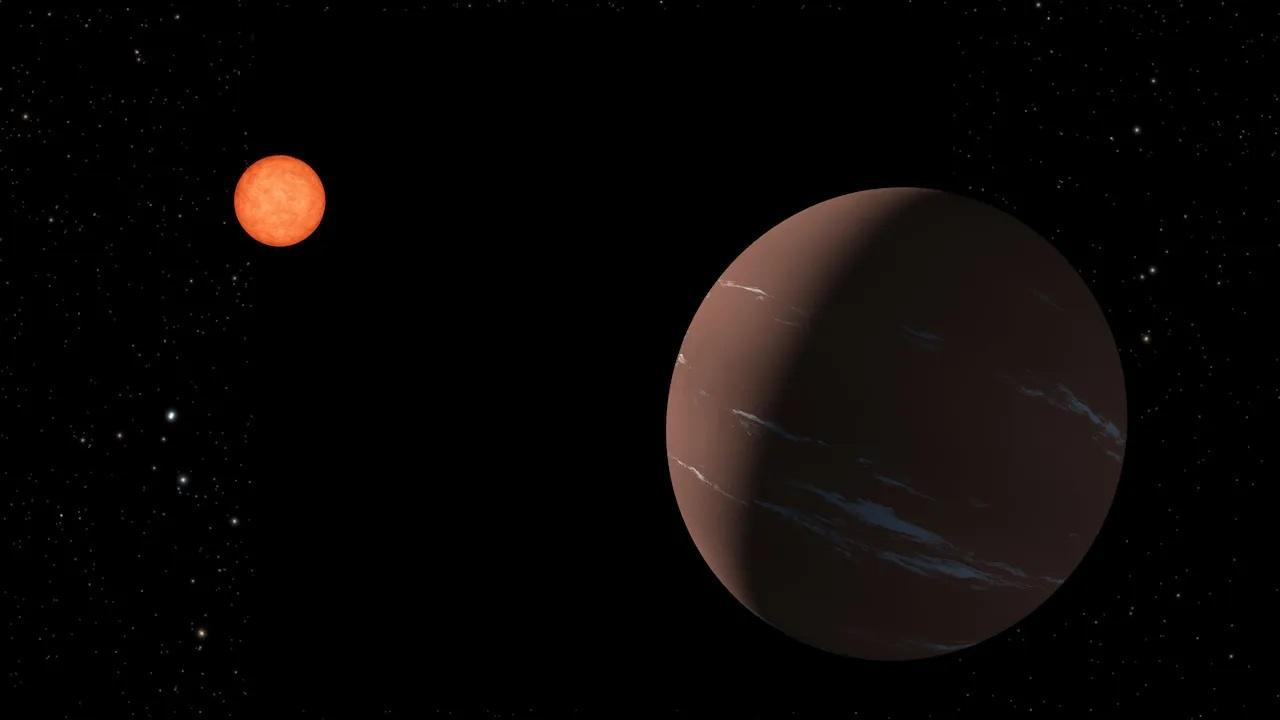

Besides Earth, the Red Planet is considered the most habitable - meaning suitable to live on - planet in our solar system.

But this doesn't mean people are able to move there straight away.

When will humans be able to live on Mars?

- Published16 October 2015

Would you fancy 'living on Mars' for a year?

- Published28 June 2023

Five questions about water on Mars

- Published29 September 2015

One of the main challenges is making the atmosphere suitable for humans, through a process called terraforming.

Dry river valleys are visible across the surface showing that the icy planet had flowing streams as recently as 600 thousands years ago.

Previous ideas on how to bring back water to the planet have ranged from giant mirrors in orbit to heat up Mars, or pumping gases such as methane, which trap heat, into the planet's atmosphere.

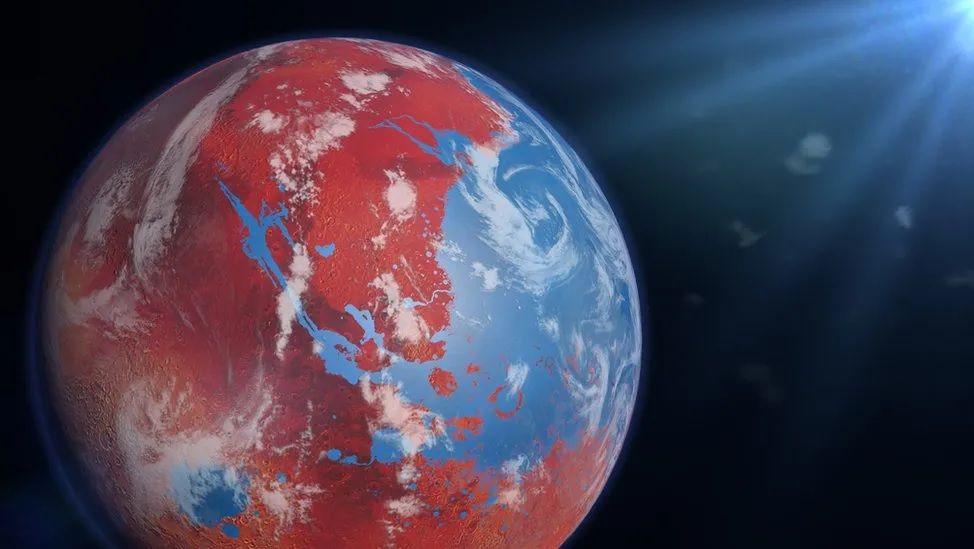

Between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago, Mars had a massive ocean on its surface called Oceanus Borealis

Many of the methods are difficult to put into action but now a study claims to have an idea which could be an easier way to warm up the planet.

Lead author Samaneh Ansari at the Northwestern University and colleagues looked at how engineered dust made from materials that can been mined from Martian rocks, could raise the planet's temperature and melt ice.

The dust, made up of tiny metallic rods, each nine millionths of a metre, would be pumped into the atmosphere.

The small dust clouds could then remain for around 10 years, small enough to allow sunlight through, but also able to prevent heat from escaping from the atmosphere.

The researchers writing in the journal Science Advances say that their experiments indicate that a steady release of the dust at 30 litres per second would warm Mars and start to melt the ice.

“You'd still need millions of tons to warm the planet, but that’s five thousand times less than you would need with previous proposals to globally warm Mars,” said co-author, Edwin Kite from the University of Chicago.

“This significantly increases the feasibility of the project.”

- Published6 June 2024

- Published29 March 2024

- Published5 February 2024