Some pterosaurs soared while others flapped, new research shows

Some pterosaurs would have flapped their wings to fly like many birds today, while others soared like vultures

- Published

How pterosaurs took to the skies is a question researchers have been trying to figure out for many years.

Some have even wondered whether the largest pterosaurs could fly at all.

Now, 3D fossils of two different pterosaur species, including one which is new to science, have led scientists to believe that not only could the largest pterosaurs take to the air, but their flight styles differed too.

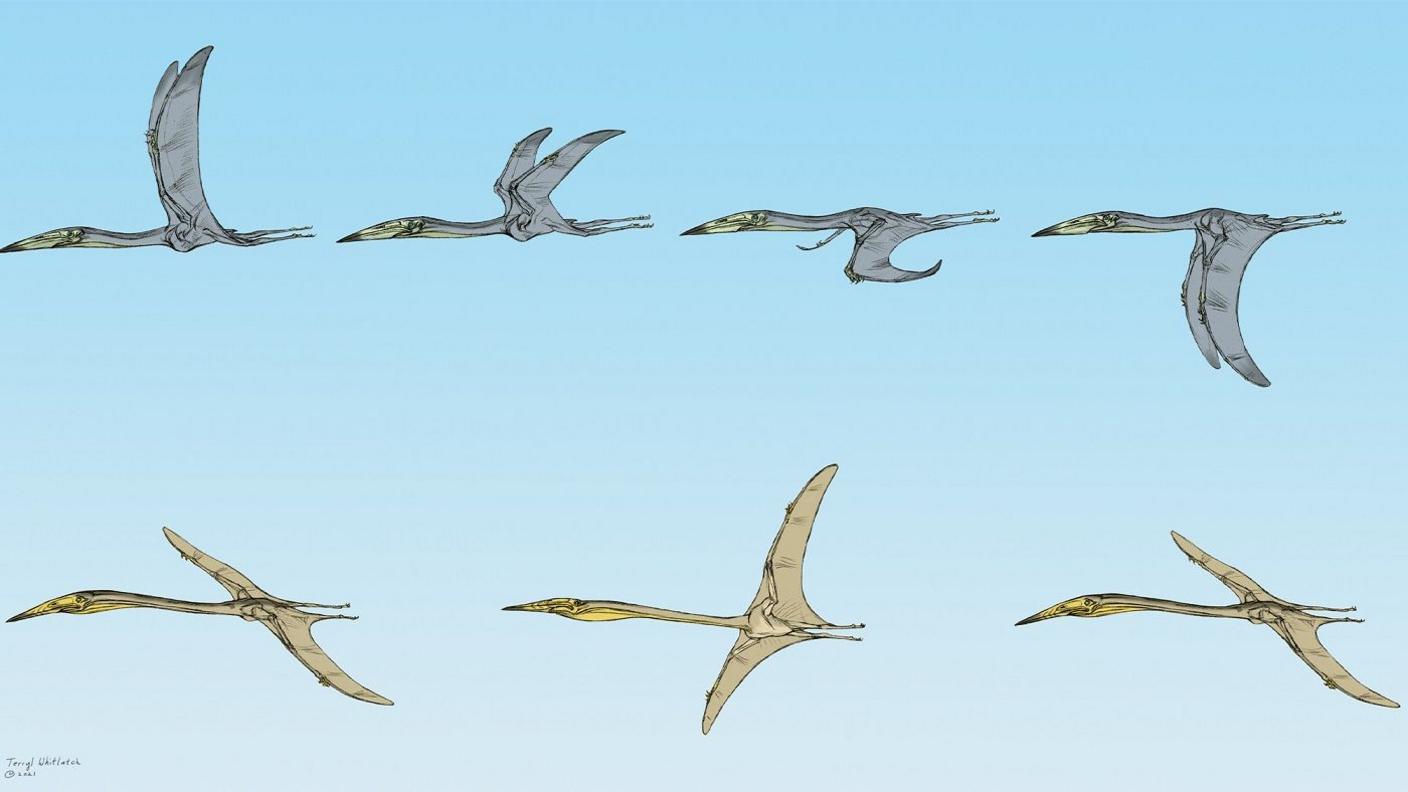

Experts from the US, Jordan and Saudi Arabia say some of the giant reptiles, which lived on the Earth millions of years ago, would have flapped their wings to fly like many birds today, while others soared like vultures.

More like this

Isle of Wight dino is 'most complete' in more than 100 years

- Published10 July 2024

'Oldest EVER' dinosaur fossil found in Brazil

- Published8 August 2024

New species of pterosaur with 'muscular tongue' discovered

- Published12 June 2024

The fossils, which belong to pterosaur species from the azhdarchoid family and date back to at least 66-million-years-ago, were preserved within two different sites in Afro-Arabia.

The research team who worked on the study used special high quality CT scans to look at the internal structure of the wing bones.

“The dig team was extremely surprised to find three-dimensionally preserved pterosaur bones, this is a very rare occurrence,” explains lead author Dr Kierstin Rosenbach, from the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences of the University of Michigan.

“Since pterosaur bones are hollow, they are very fragile and are more likely to be found flattened like a pancake, if they are preserved at all.

“With 3D preservation being so rare, we do not have a lot of information about what pterosaur bones look like on the inside, so I wanted to CT scan them."

Pterosaurs lived on the Earth at least 66 million years ago

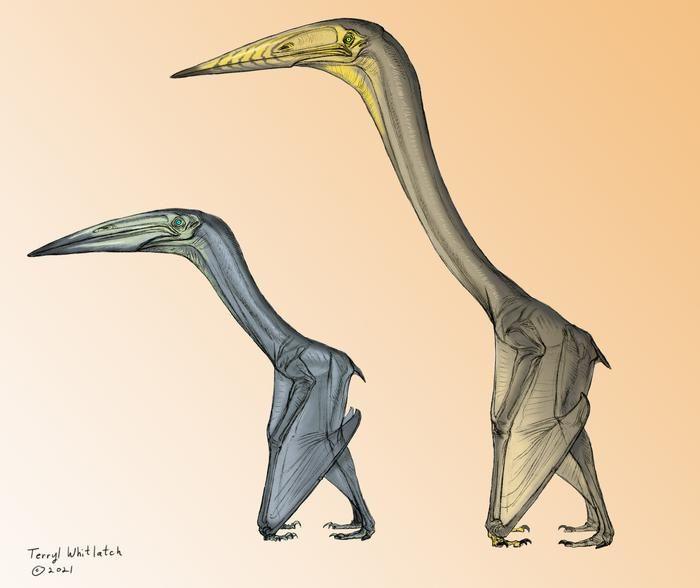

The images from the CT scans revealed the inside of the first fossil, which came from a pterosaur with a massive 10-metre wingspan, contains a series of ridges that spiral up and down the bone.

This is similar to the structures found inside the wing bones of vultures, which help the birds soar.

The other fossil analysed was part of a pterosaur with a five-metre wingspan. The CT scans revealed the structure of its flight bones was completely different from that of the bigger reptile.

The interior of the flight bones were arranged in criss-crossed pattern that match those found in the wing bones of modern flapping birds.

This suggests it was adapted to flapping, although it may have also used other flight styles too.

The pterosaur remains were found in Afro-Arabia

Experts say the discovery of the flight styles in differently-sized pterosaurs is “exciting” as it opens a window into how these animals lived.

It also highlights interesting questions about how the reptile's flight style linked with their body size, and which flight style was more common among pterosaurs.

“There is such limited information on the internal bone structure of pterosaurs across time, it is difficult to say with certainty which flight style came first,” Dr Rosenbach explained.

“If we look to other flying vertebrate groups, birds and bats, we can see that flapping is by far the most common flight behaviour.

“Even birds that soar or glide require some flapping to get in the air and maintain flight.

“This leads me to believe that flapping flight is the default condition, and that the behaviour of soaring would perhaps evolve later if it were advantageous for the pterosaur population in a specific environment, in this case the open ocean.”